Malta is about to celebrate its 50th anniversary of Independence on 21 September. The road to Independence began with a call for integration with Great Britain, and was paved with episodes of civil unrest and finally saw the proud raising of the national flag when Independence was won.

Historian Professor Henry Frendo sat down with The Malta Independent to describe the journey.

“Patriotic and nationalist sentiments… the desire for greater autonomy had been a long-standing concern at the time. There were petitions sent to London for Malta to have its own representative council, demands for the removal of censorship, for the elected principle (right to vote) and by 1850 these demands were met,” Professor Frendo explained. This was the beginning of a journey towards one of Malta’s most historic moments.

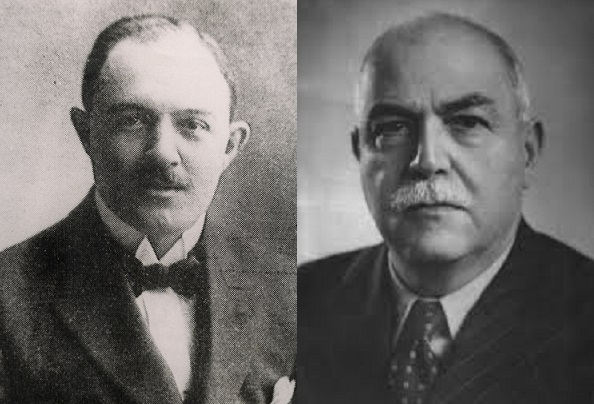

(Sir Ugo Mifsud and Enrico Mizzi)

There was no linear constitutional or political development. When the dominions were granted more autonomous status within the British Empire in the 1930s, the Nationalist party sent a delegation to London composed of Prime Minister Ugo Mifsud and Enrico Mizzi and requested that henceforth, Malta should no longer report to the colonial office, but should be transferred to the Dominion Office, Professor Frendo continued. “They were basically asking for Malta’s constitutional status to be re-thought as a dominion, rather than that of a fortress colony. The result was the abolition of Malta’s constitution in 1933”.

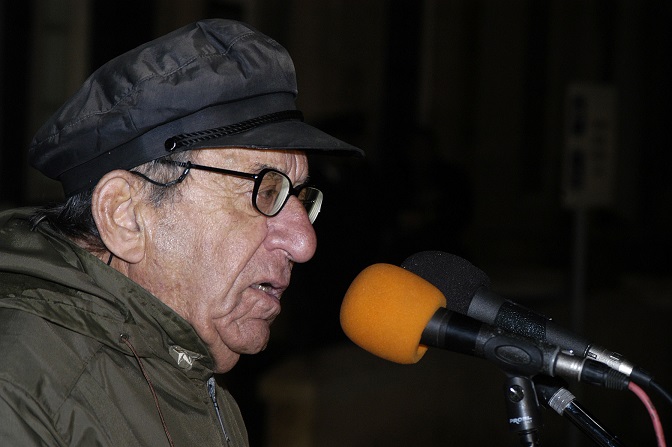

(Dom Mintoff)

“If one had to plot a graph, of Maltese resistance to colonial rule, certainly on the Nationalist side, one would find it pointing towards political autonomy. On the Labour side, it’s a bit more equivocal as he who gives, dominates. The British created jobs for the working class… in the dockyard, the army and the merchant marine. You take care of the hand that feeds you. This doesn’t mean that they were colonialists or collaborators," he said.

“I’m not saying the Nationalists were saints. Mintoff at the time tried to integrate Malta into the United Kingdom. If one looks at the Labour Party manifestos of 1950 and 1955, the Labour Party’s main slogan was ‘integration or self-determination’”. The main priority for the Labour Party was to make Malta an integral part of the UK, with as many benefits accruing to the Maltese as the residents in the UK had, he said. “Partly because the Labour Party was correctly sensing that disengagement, from the UK side, was in the air,” Frendo said. “In 1957, there was the defence white paper and it was clear that Britain would be cutting its defence expenditure. For Malta, that meant the Royal Dockyard, army and navy that employed thousands of people. So, if you can’t beat them join them. I think that was the logic behind Mintoff’s approach”. Most of those who voted in the referendum voted in favour of becoming part of the UK.

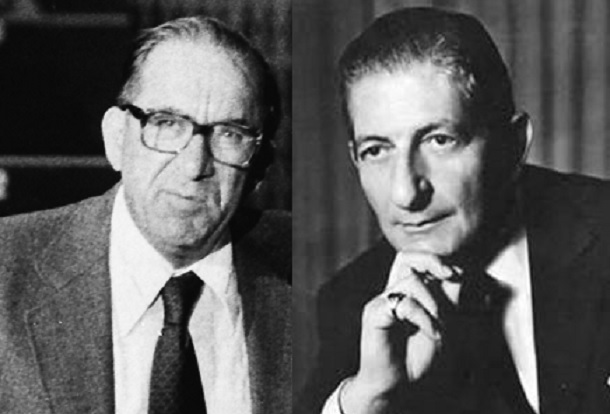

(Archbishop Mgr Gonzi with Labour leader Dom Mintoff)

The denial of integration

There are a few main factors as to why integration didn’t succeed. “First off, the Nationalists boycotted that referendum and the Church under Archbishop Gonzi wanted certain guarantees. He was worried that Malta would become part of a country that was not historically catholic. As it turned out, of all those entitled to vote, a large portion chose not to vote. In 1956 there was the Suez Canal crisis and the UK and French attempts to gain control failed, so de-colonisation began to take root.

“Initially a number of leading British peers and politicians were tickled pink at Malta wanting to join the UK as everyone else was trying to distance themselves and de-colonialize. It went against the grain. The only other part of the empire of like mind at the time was Gibraltar. However Malta is a different kettle of fish as we are bigger, have more harbours, more people, whilst Gibraltar controls the entrance to the Mediterranean,” he said. Mintoff wanted equivalence which, economically speaking was not easy, he explained. “One of the referendum slogans was ‘£9 a week’, which would have been a bonanza for Malta. Mintoff played the Oliver Twist scenario, constantly asking for more and I think the Brits lost their fervour. He believed he had it in the bag, holding the referendum so quickly.

So when the goodwill dissipated, Mintoff fell back on the second part of the Party’s slogan… self-determination. He pushed this in Parliament and was supported by the then Nationalist Party Leader Borg Olivier, who had wanted it all along”. Mintoff then resigned saying he will “lead from the squares”, Prof. Frendo said. “Saying' British Get Out'… 'British Go Home'. The Nationalist party didn’t promote this form of politics. I think they believed it had a totalitarian tinge to it. The British, after Mintoff’s resignation, offered the position of Prime Minister to Borg Olivier, who declined, asking for an election. The British didn’t hold one and they returned Malta to colonial rule and no elections were held until 1962”.

There were demonstrations and riots at the time, with many young people throwing stones at the police up on Corradino hill, he said. “I think Mintoff wanted to give a sign to the British that they would not have an easy time in Malta. That the Maltese would cause trouble. The Nationalist Party was less inclined towards this kind of street behaviour. They had a largely different following. There were working class nationalists as well but they were different”. The General Workers Union had also called a general strike so there was both political and industrial unrest, he explained. The Church was also vocal in its condemnation of violence. “Labour interpreted this as a condemnation if its actions how- ever I believe the Archbishop was just condemning violence”. Mintoff then shifted gears and began to speak about neutrality and un-alignment, “allying with the AAPSO (Afro-Asian Peoples' Solidarity Organization) , with the likes of Egypt, Yugoslavia and Indonesia. This was at the time of the Cuban Missile crisis, during the height of the Cold War”. “Archbishop Gonzi and Mintoff then fell-out big time. Gonzi saw himself as the leader of the flock, he had a very old mentality being born in the 1800s”.

The Blood Commission

Following this, the Blood Commission arrived in Malta, led by Sir Hilary Blood and was trying to find a way to draw Malta back to Colonial rule. Both the Nationalist and Labour party’s refused to deal with it, and smaller parties, such as that of Mabel Strickland, had discussions with them, he added. “They spoke of greater autonomy but didn’t propose independence as such. Eventually, as a result of the Blood Commission, elections were called in 1962. There was considerable tension during that time. Soviet and American fleets were parading around the Mediterranean. The mentality was that Malta was a fortress in the middle, with the best harbours,” he explained.

“Mintoff had proposed the Six Points, which the Church had opposed, including civil marriage, the end of ecclesiastical censorship, freedom of conscience... Eventually these be- came the norm but at the time they were seen as a threat. “Today one would say it was an exaggerated posture which didn’t help the Labour Party one bit. I was once told on TV by Toni Abela that the Nationalists had taken political advantage of this. In response, I said that in politics, if the wind is blowing in our favour you don’t duck. In the end, even the support for the smaller parties went to the Na- tionalist Party. There was a movement at the time, one which saw those voting for the smaller parties moving to the Nationalist party to defeat Labour. The Nationalists won with an overwhelming majority. Interestingly enough, the Labour Party was more organised, with their own media and youth movement”. When Borg Olivier won, he successfully negotiated to remove some constitutional measures that he disagreed with, such as the police force being under the British government, Professor Frendo explained.

(George Borg Olivier, the father of Malta's independence)

“Then he insisted on receiving financial assistance to help balance out the budget etc. The British offered him £100,000 and Borg Olivier retorted; ‘I did not come here to make a silver collection’. This wouldn’t have solved Malta’s financial problem. He then went to the Savoy Hotel and drafted the letter demanding Malta’s Independence. ‘I demand for my country, the urgent grant of its independence’. It was his way of telling the British to make way”.

Disengagement

The time had come for the two countries to part ways as Britain wanted to disengage and Malta wanted to engage in its own interests. “If you look at the essence of policy, the two parties in Malta weren’t far apart and both manifestos at the time were aimed at gaining independence”. Following Independence, the other small parties at the time began to fizzle out, he said. “In the 1966 elections not a single small party returned a member to Parliament”. “The terms of Malta’s Independence saw Malta receive £50 million to help the country diversify its economy from one reliant on Britain to a country dependant on its own economy. In addition, Britain was able to hold on to some military facilities, due to the cold war situation, for a number of years. One can argue that this was in our defence as having a British base, although reduced, played a role in keeping Malta stable through this transition and helped grab foreign investment,” Frendo explained.

“Malta’s Independence ceremony was very emotional. The Maltese flag was raised, thou- sands of people celebrating in Floriana… unfortunately there was a small crowd loyal to Mintoff booing. Mintoff was against the way Independence was handled as his six points were not included in the constitution. Had the six points been included, it would have been much harder to gain independence. Interestingly enough, the British Prime Minister was hoping that the independence referendum in 1964 would fail, so it’s not as though the Brits were hoping for Maltese independence”. Malta’s Independence was relatively peaceful in comparison with other independence grants throughout the colonies, he said. “By 1964, a large number of colonies had already gained independence. Unfortunately you get constitutions not worth the paper they are written on”.

“Taking a long term view of Malta’s independence over the past half century, despite the fear and problems particularly during the 70s and 80s, we landed on our feet and today Malta is a relatively free and democratic island state, taking its place in the history of nations. That is much more than can be said about many other former colonies. There hasn’t been a uniform route to independence, or rather successful independence”, he said.

“Malta has taken a step forward recently. Unfortunately, Mintoff had this habit of always expecting to be in the right and not being tolerant of those who oppose him or succeed without him. Having succeeded and inherited an independent and sovereign state in 1971, he promptly abolished independence as our national day, replacing it a number of times, basically unbalancing the Maltese psyche. Today we are the only country in the world without a national day, but I am happy to see now that people are seeing Independence day as an important event. There are moments in time when a country must rise above partisanship, the country’s independence is one of those times. Somebody had to commemorate independence after it was removed from being a national day, and the Nationalist Party did, resulting in the holiday becoming more partisan. “Today we have reached a state of maturity, where at least everyone is saying that this is the 50th anniversary of our independence, let’s all celebrate,” Frendo concluded.