From nomination to election – a series of articles leading to the election of a new President of the United States of America

An old joke in the United States runs as follows: A woman had two sons. One went off to sea, the other became Vice President of the United States. Neither was ever heard of again.

One paradox of the executive office is the gargantuan disparity of power and prestige between the President, and the deputy, the Vice President (VP) of the United States. The role has traditionally had minor significance mainly due to the relatively unknown names that were appointed to the position, and the rather unclear job description that the role carries. Vice Presidents are the first hand eye witnesses to power, yet they can also be mere passive bystanders of an important passage of history. John Adams, first VP of the United States, famously quipped “I’m nothing, but I could be everything”.

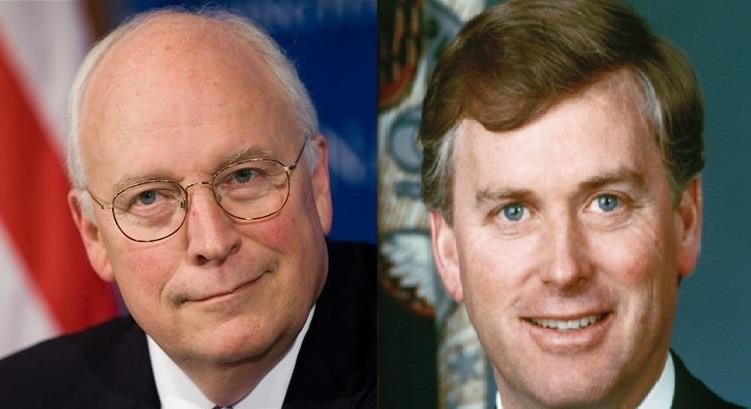

Left, Influential - Dick Cheney (2001-2009) and Right, Ineffectual - Dan Quayle (1989-1993).

The key to defining the VP’s influence in American politics is held by the President. Some VPs have had significant roles (Al Gore led the pro-environment agenda during the Clinton Presidency) and close access to power (Dick Cheney had huge influence on defence and foreign policy matters during the George W. Bush Presidency). Others remained mere footnotes in history.

Dan Quayle, Senator from Indiana and VP to George H.W. Bush (1989-1993) became a franchise for stupidity in high office. Every time he spoke he was subject to derision and no all-out effort could restore his reputation or legacy. Considering the string of successes of Bush (41) in foreign policy, Quayle was ill-placed and ill-suited to an office that, while limited in powers, still demanded a modicum of esteem and self-respect.

Constitutional Role

A few months before leaving office, Hubert Humphrey recalled his experience as VP to Lyndon Johnson (1965-69) as one “like being naked in the middle of a blizzard with no one to even offer you a match to keep you warm… You are trapped, vulnerable and alone, and it does not matter who happens to be president.” Perhaps Humphrey could not be blamed for having felt this way. The Constitution has provided only a very partial remedy to this boredom. Whereas the Vice President is not constitutionally vested with any executive power, the VP is mandated to preside over the Senate (Article 2) and can only vote to break a tie (there have been 244 tie-breaking votes in the history of the Senate). The qualifications necessary to become VP are the same for a President; being a natural born citizens of the US, at least 35 years old, and having been an inhabitant of the United States for at least 14 years.

John N. Garner (right), VP to FDR (1933-1941). According to him the Vice Presidency was “not worth a bucket of warm piss” © FDR library

The selection of VPs has varied. The natural path to becoming one is having been on the ticket for the general election with the Presidential nominee. This process however has had a number of variations in history. When Truman was approached for the job in 1944, his response to FDR (through intermediaries) was “Tell him to go to hell.” He eventually accepted nomination and succeeded FDR as President. In 1960, then Senator Kennedy, a Roman Catholic, made a strategic choice in picking a Texan and a Protestant, Lyndon B. Johnson to secure party unity and curry favour with the South.

The next Vice President

Author Stephen Graubard argues that “by the last decades of the century”, each Vice President was “more than just a loyal associate”. Subservience is not, unlike some political systems an institutional requirement to keep the spotlight on the President, but a conventional etiquette that demonstrates attitude and personality. When Eisenhower (1955) suffered a minor heart attack, Nixon (VP 1952-1960) feared by some of being overly ambitious, earned the respect of many by handling Ike’s absences with tact and style. Eisenhower would also suffer a stroke in 1957.

The current candidates running for President of the United States have defied a few odds in the choice of their running mates. Clinton opted for Tim Kaine (58, Senator from Virginia) while Trump picked Mike Pence (57, Governor of Indiana). Both are experienced politicians, yet nationally they are relatively unknown quantities. Kaine is a progressive moderate who also served as Governor. Rumour had it that he topped Obama’s preferred list for VP before Biden was chosen. He is a Roman Catholic, against abortion (though supportive of women being able to make their own decisions) and against capital punishment (11 executions took place while he was Governor). His attention to detail in policy-making and savviness in public relations would be an asset to Clinton. He will also need to advise her on how to stay out of trouble.

Mike Pence has a complicated religious status. A ‘born-again catholic evangelical’, Pence is a conservative and member of the Tea Party movement. His name only came to the fore a few days before the actual announcements. It may still seem baffling why Trump chose him as his running mate. He does not appeal to the Latino vote and is not likely to garner popularity with the middle ground of the political spectrum. He is a fervent anti-Keynesian (had opposed the bail-out of General Motors and Chrysler) and advocates laissez-faire economics, contrasting already with some of the views pronounced by Trump. With him, Trump can secure the right and right-of-centre vote, an endorser of traditional family values and an avowed opponent to government intervention (in economy).

The American people and the rest of the world will get a closer glimpse of the next Vice President during the vice presidential debate a few days before the election. In 2008, over 70 million viewers had watched Joe Biden debating Sarah Palin. As Gerald Ford remarked, the Vice Presidency (and the Presidency) were never a reward, but ‘a duty to be done’.

Fourteen VPs became Presidents of the United States – eight of them succeeded a dying President (four after assassination, four after death from natural causes).

Four VPs went directly from their office to become Presidents: John Adams (2), Thomas Jefferson (3), Martin Van Buren (8) and George H.W. Bush (41).

Three VPs won the Nobel Prize: Theodore Roosevelt (1906), Charles Dawes (1925) and Al Gore (2007).

Two VPs were not elected to office, but were appointed according to the 25th Amendment: Gerald Ford and Nelson Rockefeller. Ford (38) became President after Nixon’s (37) resignation.

Two VPs served as acting Presidents while the President was incapacitated: George H.W. Bush (1985) while Reagan was undergoing surgery, and Dick Cheney (2002 and 2007) when George W. Bush was sedated for medical procedures.