The objectives of the church and of abstract art are fundamentally incompatible. The former exerts its influence over the majority and requires the support of the masses. The latter, albeit its aims for a democratic language, unwittingly enforced the exclusivity of art. This is because abstraction is a pictorial art originally made by and for an artistic elite. Today abstraction has opened up new artistic directions, but has also become fashionable and derivative.

When Emvin Cremona started to produce abstract compositions in the 1950s, this sphere of art had developed a global following and was innovative. Parts of the world (New York City, London), celebrated non-figurative depictions, whilst others maintained an aversion to objects devoid of recognisable objectivity.

The Spanish philosopher José Ortega y Gasset was quite correct in saying that "...to the majority of people aesthetic pleasure means a state of mind which is essentially indistinguishable from their ordinary behaviour...the object towards which their attention and, consequently, all their other mental activities are directed is the same as in daily life: people and passions. By art they understand a means through which they are brought in contact with interesting human affairs...a work that does not invite sentimental intervention leaves them without a cue." (The Dehumanization of Art, 1925).

Traditional or figurative art is relatable because it portrays a likeness to the object world. Things are identifiable, hence familiar. Furthermore, it conveys emotions through facial features, gestures, movement, descriptions of nature, symbols, and other conventional devices. Compassion is not only permitted but is necessary for the artwork to achieve its raison d'être.

Abstraction interfered with traditional art's legibility. Only the minority were drawn to it and could handle its detachment from physical reality to manifest a new visual dimension.

Cremona was acutely aware of cosmopolitan artistic currents, having studied in London and Paris in the mid to late 1940s. However, he was simultaneously building up a solid and lasting reputation as a sacred art painter in Malta, where the most successful artists were, until recently, those who worked for the church. He quite explicitly wanted to be an influential artist. Cremona was ambitious and knowledgeable.

The paintings that he produced for Maltese and Gozitan churches were positively received. However, during an interview held with Dominic Cutajar in 1979, Cremona dismissed his church works as irrelevant to the history of twentieth-century Maltese art as he did not consider this sphere of his life's work to be 'serious'. This is quite a significant statement to be made by an artist specifically renowned and respected for the same works that he himself showed contempt towards.

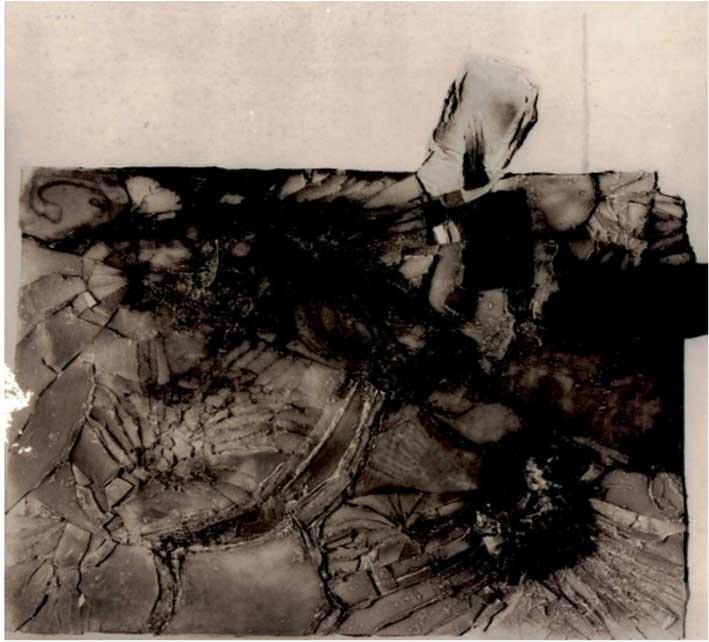

He clearly had an international dimension in mind, and knew what cosmopolitan audiences were after. This may be observed by looking at the type of art Cremona exhibited overseas. Cremona's abstracts were shown at the Commonwealth Institute Art Gallery in London in a number of international and also Maltese collective shows. Of all the Maltese modern artists, it was his art that was promoted most by this gallery. For each exhibition, Cremona submitted his more experimental works and never exposed his locally-known religious art to the cosmopolitan London audience. The Cremona exhibited in London and the Cremona popularly known in Malta appear to be two separate artists.

Such evidence casts Cremona into a doubtful light; was he bowing down to the demands of two separate publics, or did he feel more comfortable with finding unquestioned recognition in London?

Still, Cremona's figurative church works adhered to the national canon. His will to create was subservient to hegemonic norms, to the popular will for legibility and sentimental articulation. Giuseppe Schembri Bonaci in his study on Willie Apap's and Cremona's depictions of St.Paul wrote; "Only art that is striving to crack out of such a canonical egg can manifest a universal Kunstwollen." The term Kunstwollen, conceptualised by art historian Alois Riegl, refers to an 'art-will'; the ability of art to transcend the boundaries of convention.

Last Thursday, Dr. Schembri Bonaci and myself presented a discussion on Cremona's art, abstraction, and the artist's barefaced participation in the vehemently anti-modernist 1960 St. Paul Centenary. His central involvement in an event that celebrated the religious-patriarchal status quo ideologically clashed with his liberal, expressive abstracts bearing no specific traditional signs and symbols. Furthermore, this all occurred at the time of the interdett injustices which caused many Maltese to suffer institutionalised persecution. Such actions are politically loaded but hardly ever questioned.

As argued by Schembri Bonaci, the Perspex St. Paul produced as part of the Centenary artistic programme is a large image of the saint that bears strong formal allusions to twentieth-century monuments venerating dictatorial regimes. Paradoxically, the militant, sword-wielding saint commissioned by the anti-soviet church looks quite similar to certain monuments found in soviet states. The main difference is in the choice of materials. Whereas these monuments are made of bronze, marble, stone, Cremona's rendition appears fragile due to the use of perspex.

It is troubling that an artist would support the church's decree against human liberty and then indulge in a language of artistic liberty when not producing commissioned works. This political conflict evinces the problems of being an artist in twentieth-century Malta. However, it would be counter-productive to find excuses for Cremona's deliberate choices on the basis of financial interests. No one can be denied the opportunity to become successful, yet the fact that Cremona as a singular artist quite easily oscillated between figuration for the church and abstraction for his private studio and overseas audience posits a rather skewed definition of artistic freedom.

In spite of the aversion to unconventional art in Malta, artists such as Josef Kalleya, Carmelo Mangion, Antoine Camilleri and others never compromised their art. Some were marginalised because of their defiance. Cremona, on the other hand, practically monopolised the 'official' Maltese arts scene because he was willing to make compromises.

So yes, it is possible to link abstraction with the church and with its politics once these became intertwined in Cremona's art.

Emvin Cremona: Dnub il-Mejjet and Abstraction was organised by the Strada Stretta Concept under the auspices of the Valletta 2018 Foundation