'The Flesh & The Spirit’ - that's a curious name. What is the main concept behind this exhibition - just a few days away from opening to the public - and why is it being held this year?

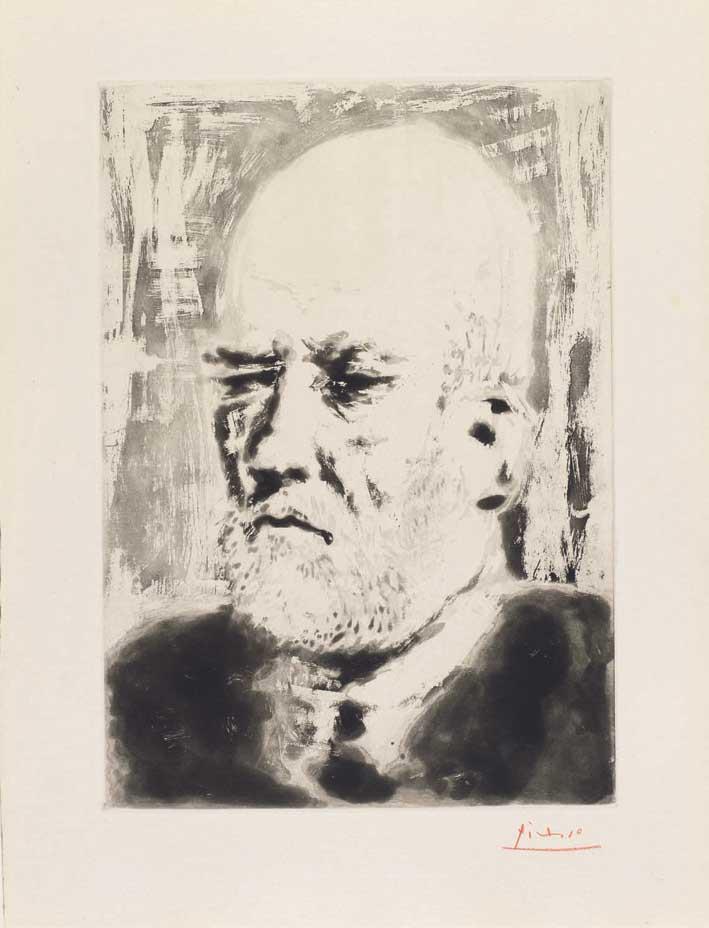

In truth, the exhibition forms part of a major international project running between 2017 and 2019, called Picasso-Méditerranée, which is an initiative of the Musée Picasso in Paris focussing on Picasso's relationship with the Mediterranean. Malta, which is currently carrying the title of 'European Capital of Culture,' has also been invited to participate alongside sixty other museums! This exhibition in particular, will see Picasso's Vollard Suite together with a selection of paintings by Joan Miró. Notably, both artists have experienced insularity, in their own way and for somewhat different reasons. Although two very different artists, stylistically and conceptually, a space for an different kind of dialogue is thus being encouraged - a space that is as much about the palpable and the finite, as it is about the abstract and infinite - about the flesh as much as the spirit.

Pablo Picasso and Joan Miró: two big names in the art-world. But which side to them will we see in the exhibition?

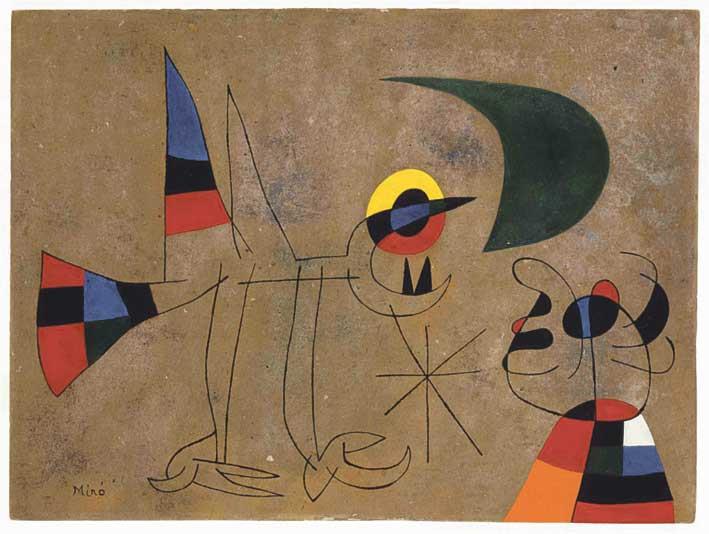

Miró's work, on the other hand, might easily mislead us into thinking that he was solely concerned with things of the spirit, with memories trapped so far deep into the subconscious or unconscious mind, they are rendered abstract and unrecognizable. As in Picasso's Vollard Suite, there is seemingly no chronological order in Miró's selected works, despite being painted over a much longer period of time - thirty years, in fact. Nor can we say much about narrative. Indeed, there is little to tie his works to the flesh, so to speak, even though the artist is seemingly obsessed with motifs that actually refer to the 'femme' (woman) or to 'oiseaux' (birds), and the 'étoiles' (stars), for instance. But these motifs belong far more to the subconscious, perhaps unconquerable, realm.

Having said this, however, Miró himself admits that there could not have been a more 'real' basis to his art; 'have you ever heard of abstraction-abstraction?' Miró once asked Georges Duthuit in an interview. 'They ask me into their deserted house, as if the marks I put on a canvas did not correspond to a concrete representation of my mind, did not possess a profound reality, were not a part of the real itself.' Miró, here, provides us with a key to his work: one must first refer and reflect on the 'real', on what we experience in the flesh, in order to unlock the realm of the spirit.

So, one might say that through the artworks on show, these two artists are challenging the way we see or, even, think of art...

Somewhat less subtly than Picasso, Miró once exclaimed, rather provocatively: 'The only thing that's clear to me is that I intend to destroy, destroy everything that exists in painting.' This was in 1931, well before he produced the works which feature in this exhibition. But in a way, his commitment to 'destroy' a certain mentality of art holds true, especially in his later works. If anything, he calls the finality of art into question, while also redefining his identity not as 'an engraver or a painter, but rather as someone who tends to express himself however he can.' Art, it seems, was no longer a point of reference for Miró, less so that of traditional aesthetics, subject matter or some formal standards of beauty. It was as if Miró was trying to say that if one is to be free - and his or her art for that matter - then one had to cut those ties with the past, completely. 'I had to stop being Miró,' he claimed, 'that is, a Spanish painter belonging to a society limited by national boundaries and social and bureaucratic conventions. In other words, one must move towards anonymity.'

There seems to be a sense of conflict - internal, external - all around. Even in bringing the 'flesh' and the 'spirit' together, this almost automatically evokes the idea of conflict. Even today, this would seem rather relevant to us.

Yes, but the exhibition also shows the extent to which the two are linked. It is difficult to draw the line between the 'flesh' and the 'spirit' as it is not simply a matter of "where one ends, the other begins." This will be the challenge, or invitation rather, of every viewer: to glimpse into the personal tribulations of Picasso, indeed almost like one of his own etched voyeurs; or to follow Miró's compositions along some unknown, mysterious route.

In either case, what one hopes for is an experience of freedom, of untangling the mind from some preset notion of art, of what it should be, and what it can or should do. This perhaps, is the ultimate expression of Picasso and Miró: both ached for freedom, trapped as they were in a world they could not control.

'Picasso and Miró: The Flesh and the Spirit' is an exhibition organised by Fundación MAPFRE in collaboration with the Office of the President of Malta and Fondazzjoni Patrimonju Malti.