The power of the big screen is difficult to wholly quantify. Films, documentaries, television series portray stories we’d have never heard of before, bring to life scenarios we’d have never seen before, and move us in ways we’d have never been moved before. The onus for such works normally falls onto the actors – they are the faces of the project after all. However, the power of the big screen wouldn’t be such if it were not for those manning the cameras on set, and the art studios in office.

David Serge is one of those whose work is behind the camera and in post-production. He always knew that he had an incredible passion for film-making, and having graduated from the University of Malta with a Bachelor’s degree of Communications (Hons) in 2003 and having seen his thesis film winning the Golden Knight award; he applied to study cinematography abroad in London. He was shortlisted amongst the last 10 candidates but then didn’t make the final six, who were admitted to the National Film and Television School.

“I took it really badly because I was young, passionate, and I thought I had what it took to get in, so I spent the next couple of years learning by myself – I became an auto-didactic”, Serge explains. As he was teaching himself he met Matthew Pullicino, and from there a certain “synergy” was created which soon bloomed into the creation of a company.

Starting from a couple of commercials, Serge and Pullicino developed the idea and started The Bigger Picture, which was geared up to handle local clients - meaning that they used to do a lot of commercials, documentaries and short films.

In 2012 then, Stargate Studios Malta was born. Sam Nicholson, the founder of Stargate Studios – which is based in Los Angeles and has ten studios around the world – was interested in the development of the Maltese company and his decision to have a Stargate studio opened up in Malta was based on a number of factors; not least because of the visual effects talent that Serge and his team can bring to the table and because of Malta’s strategic place which can be used to handle the European market.

Since, Stargate Studios Malta has worked on 20 international series in different capacities ranging from work on series such as Grey’s Anatomy, all the way to shows requiring heavy digital work such as a series which they have just finished working on called Sabuesos, where, Serge explains, the main character is a dog. In that case, Serge explains, that they shot the Jack Russell in question on location, then scanned the dog and build a digital head for it before animating his mouth and eyes so it would have the ability to speak and gesture.

Building the Duomo “stone by stone”

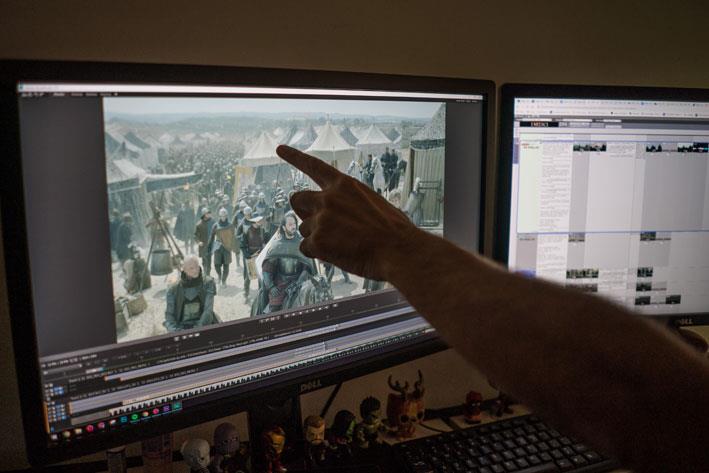

Another technically complex project which Stargate Studios Malta has been working on is the hit Italian series I Medici. Set in Florence between 1460 and the early 1500s, it centres on the infamous Medici family, which was one of the most powerful families not just in Florence, but in the whole of Italy.

Working on such a series is a technical complexity, not least because Serge and his team had to digitally reconstruct Florence’s famous Duomo, which at the time that the series is set was still under construction. In fact, whilst the base of the Duomo is built, the ‘Cupola’ remains unconstructed during the series.

Explaining the process for creating the Duomo, Serge says that it was a very complex type of shot to accomplish and to get working as close to reality as possible. The famous cathedral, Serge explains, is built up “practically stone by stone” in a 3D environment. To do so, all the blueprints of the cathedral had to be analysed in depth – both of the outside and the inside of the church.

In fact, for the cathedral’s interior, Serge and his team gained exclusive access to places in the cathedral which aren’t open to the average tourist so that they could take high quality photos for use.

The interior shots presented an altogether different technical challenge as well. There was no way that the film crew would ever get permission to film inside Florence’s Duomo for three to four weeks, and so another location had to be found. Indeed, Serge says, all the interior shots of the cathedral were in reality shot inside the church of the village of Montepulciano.

That church is four times smaller than the masterpiece in Florence, so it presented Serge and his team with a further challenge; giving the impression that the characters were talking inside a huge cathedral as opposed to the one at Montepulciano.

To do this, Serge explains, the team had to create a hybrid model of the two cathedrals. Pointing out one specific shot where the camera starts out at floor level before panning up to the inside of the still unconstructed cupola, Serge explains that the shot actually starts with the dimensions of the Montepulciano church and its columns, but it then “bends” as the camera pans up to create the visual that the shot is actually taking place in a bigger cathedral which is closer to the one in Florence rather than the one in Montepulciano.

A further complication which affected building the model used for the interior Duomo shots, Serge says, was that the Montepulciano church was built in a classical style, which meant that its arches are more rounded, whilst Florence’s Duomo is built in a more Gothic style, meaning that its arches are more elongated. These architectural intricacies all had to be factored in to create a model that could serve all circumstances.

The next step is to analyse and take into account the cathedral’s external and internal textures. The high detail photos which Serge and his team took at the cathedral are complemented with things such as drone shots so to give the model of the cathedral the proper textures so that it begins to look like the cathedral itself.

The final stage is taking into account the lighting. Andre Grima, who is the team’s 3D supervisor would be on location in Florence to analyse how the light hits the cathedral in real life, so that the team could then reproduce that into the model.

The shot then leaves the world of 3D and goes into the world of 2D, supervised by Jonathan Caruana, where all the separate layers are brought together.

Next, the modern city around the Duomo is cleaned out using a process called “rotoscoping”, and the modern city is painted out by the matte painting department before being replaced by its medieval equivalent, complete with the old city walls.

Only after this process, which involves many departments and many people and can become quite the task logistically speaking, can the compositors finally bring every element together to create the full shot as it is aired on television, with modern Florence being replaced by medieval Florence, and the famous Duomo being displayed without its iconic cupola.

An indigenous film industry in Malta is not sustainable just yet

Malta’s film industry has grown somewhat in the recent years especially in terms of films being shot on the island; but is that growth being complemented by Maltese people who are being properly educated and prepared to enter the industry?

Firstly, Serge doesn’t think that Malta actually has its own film industry just yet; what the island does have is a “rental industry”, meaning that foreigners use Malta as a location to shoot. There definitely isn’t an indigenous Maltese film industry yet though, Serge says before defining the word “industry” as “something that is financially viable and sustainable”, and adding again that for now, this does not exist.

What one finds today is a number of local filmmakers, who sporadically embark on a journey to produce a movie, and they do – which is “very commendable”, Serge says as it is not easy to “do a move in itself, let alone do it in a country that has no industry.” He mentions pioneering Maltese movies such as Simshar and Limestone Cowboy and calls them “great efforts at starting the industry” and says that they are a good base to continue to work off.

There is a bit of a language barrier which affects this, Serge says; producing a movie in Maltese is very limited in terms of the market and he believes that shooting movies which are not in Maltese somewhat defeats the purpose of kick-starting an indigenous industry; “what’s the point in producing a movie in English if you’re trying to stand out as Maltese?”, he questions. “It’s not an easy situation”, Serge adds, “but it doesn’t mean it cannot happen; it has happened in other small countries such as ours, but what we lack at the moment is education”.

There are University of Malta and MCAST who “do their best” in creating courses and syllabi, but the truth is, Serge says, that there are not enough – in qualitative terms – lecturers to truly make a difference. This is seen in his own company, Serge said; “we can never find someone in the visual effects department who is ready to go; we always start with someone who is interested in visual effects and then we slowly train them in the real dealings of our work”.

It’s the same in film, he says; “we don’t have directors of photography per se in Malta because there is no education system locally that prepares people to become directors, meaning that the good ones Malta does have would have generally obtained their education abroad.”

All these aspects – financial, cultural, and educational – come together and mean that it is an “uphill struggle” to be able to create an industry, Serge says.

From visual effects to production

What Stargate Malta has managed to achieve is to create a sustainable model for a visual effects company, Serge continues. This, for him, is one of their biggest accomplishments as they come from an island which has no VFX education and because VFX itself is a very specific art.

Over the years Stargate Malta has trained and given a sense of impetus to artists to help them develop by doing work at an international level, a level where “quality is uncompromised”.

Serge hopes that as a company this same philosophy is turned from visual effects into production as well. He says that Stargate Malta has plans to grow into the production scene, and they are developing feature films possibly even in collaboration with foreign co-producers, and so the future looks very good for the company’s plans to continue developing the Maltese film industry, Serge says.

He adds that the contacts that he and his team have established abroad have helped; but that at the end of the day, “it’s about the quality that you manage to deliver – it’s about artistic capabilities, technical capabilities – because at the end of the day the client is paying for that”, he concludes.