An experimental pilot project to re-nourish Balluta Bay is not considered a failure by the Malta Tourism Authority’s (MTA) environmental consultant on the project.

This year’s sand replenishment project proved controversial following reports that the sand had been washed away within a few days.

Speaking to The Malta Independent on Sunday, environmental consultant Adrian Mallia has said one must first understand how beaches work.

Meanwhile, an MTA spokesperson has also argued that the project is feasible, especially since it will be financed by the operators of the Marriott hotel for the next five years. Nevertheless, she says, the MTA “is planning a feasibility study for any similar interventions in the future.”

Environmental consultant Adrian Mallia explains that works last year started later than anticipated due to permit issues. Instead of starting in June, works began on July 31, “so we had already lost the best part.”

Mallia also explains that the most important thing to understand about beaches is that they are dynamic.

Preparation for sand pumping this year (June) - silt curtain in place

What is referred to as a beach – which is the dry part where people sunbathe – is only part of the whole system. The system includes a valley, typically a salt marsh, sand dunes, the beach and then all the rest, which is underwater. At Balluta Bay and several other beaches, this is no longer so because of disturbances to the environment due to human intervention.

What happens in a normal system is that rain flows down the valley to the sea carrying sediment that is deposited offshore. In winter, sand is lost from the beach, either inland, where it deposits and enlarges the sand dunes, or offshore. The sand that is lost to the sea deposits in what is called an offshore reservoir – such as at Għadira Bay, where the water is shallow.

Sand movement and slope a few days after nourishment under NE winds

Around April or May, the sand starts to return to the beach. Waves drag sand up from the offshore reservoir, which enlarges the beach, and wind blows sand from the dunes. This movement of sand and the resultant beach accretion or depletion depends on the strength, direction, and frequency of winds and waves on the particular beach. This movement of sand can be easily confirmed by comparing the width of beaches from year to year or, as is often reported at Għadira Bay, when sand is blown onto the road.

The system of movement of sand is typical but the coastline has been changed so much that from rocky shores, quays and jetties are now being built. The road parallel to the beach in Balluta and similar bays also stops the flow of material from land onto the beach, so “we start starving our beaches,” Mallia notes.

As a result, Mallia says, tweaking is necessary to simulate the natural flow of the system in such locations. “Over the years, the environment of Balluta Bay has been changed so much that it is completely artificial. There is no way that a beach can form there on its own,” he adds.

Day one following this years nourishment

Mallia, however, abides by the philosophy of "working with nature, understanding the location and doing as little as possible.”

In line with this, last year, rainwater pipes leading onto the beach were left there to gauge how the beach would ‘behave’ and its relative stability before infrastructural intervention took place.

After heavy rainfall, however, many commented that the rainwater had left wide channels in the sand. The sand was carried away by water that came gushing out of several storm drains that discharge onto the stairs at the back of the beach. The back part of the beach seemed to be the most badly affected area.

This year, only a small culvert has been constructed beneath the road to collect the rainwater that used to flow onto the bay, diverting this flow to the side of the beach instead. Sand level was also raised higher than last.

Mallia explains that last year, there was no slope at the end of the beach, which was also larger, and immediately the waves started to eat into the beach to form the slope. This was part of the design (in fact some 30% more sand was added) and, as expected, “the dry beach area started to get smaller relatively quickly (also in view of the late start of the project).”

The more sustainable size of the beach is how Balluta Bay is today, Mallia says.

He also notes that, last year, despite several news reports that the beach had disappeared, there was sand on the beach until a very bad storm hit the island on 24 February.

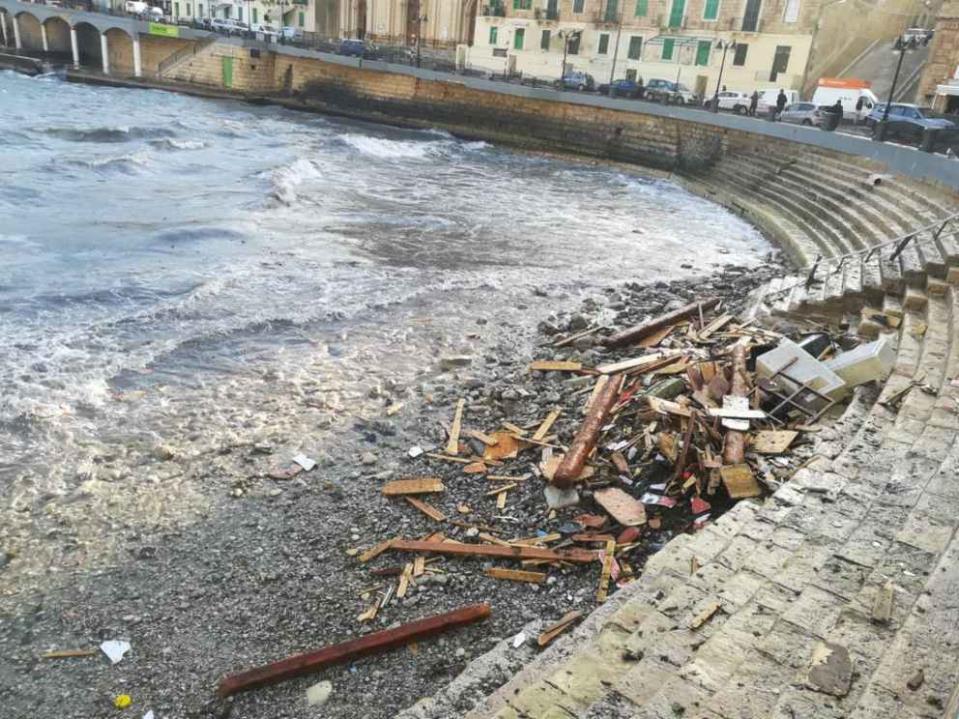

Photo from the day after the storm - 25 February

Had the storm not occurred in February, Mallia says, the project may not have been necessary this year, or at least not as much sand would have needed to be replaced.

The beach is constantly changing Mallia explained, depending on the waves and weather. Sand is deposited in the water so as long as there is a matrix – somewhere where the sand can settle – sand can be deposited once again. It could also be lost in the same way, and “that is why it remains an experiment.”

“The bay will change over summer. Sometimes it gets larger and sometimes it will get smaller. Then, over winter, the changes become more pronounced.”

This was the beach on 12 February less than two weeks before the storm

The project history - Balluta Bay works studied since 2003

Back in 2003, studies were carried out to model the beach as it was then thought that ‘hard works’, including breakwaters, could be constructed in the area. The beach was designed to be much larger than it is today, which Mallia says was ‘impossible’ as the sand would not be sustained.

Mallia began consulting for the MTA around the same time and another study was commissioned in 2005 without the breakwaters, as he believes the main approach should be ‘least intervention first’.

“We have been working on Balluta Bay since then,” he states.

Beach recovered a few days later. More changes are expected throughout summer and beyond.

The studies used local sand as well as imported sand and showed that if local sand was used, 30 per cent of it would be lost ‘under a normal type of storm’. With foreign sand, which was determined to be granite because of its size and specific gravity, around seven per cent would still be lost.

Losing granite – a foreign material – offshore was considered unacceptable by both consultants and the environment department. “This contaminates the geology, not to mention the expense involved.”

As a result, following meetings with the environment department of the time, and with the ministry, the decision was to shelve the project. Regarding the use of local sand, Mallia says that in 2007, “there was a bit of uneasiness surrounding the creation of a beach that would be lost.”

Around three years ago, the project was re-ignited and the only thing that was possible was to check if local sand from the area could be used. “We did point out that this would be a temporary beach and we knew that some sand would be lost when it rains … We made it clear that it is an experiment and it remains an experiment today.”

Last year, the re-nourishment of Balluta Bay was done using eco-grabs rather than pumps. “The idea was always to bring sand in from the surrounding area and to see how long it stays.”

Sand pumping this year

The process had been studied for a year prior and once the sand was replenished, it was monitored regularly. Up until a week before the sand was replenished this year, the old project was still being monitored.

Monitoring consists of mapping the seabed twice a year, taking turbidity readings twice a week until the water clears up, taking several photos each day at different stations on either side of the bay, as well as using beach profiles and drones to take footage from different heights.

Minimal environmental damage during re-nourishment

Sand is won from offshore borrow areas, Mallia points out, but only patches where there is bare sand are utilised. Where the dredgers are put is carefully considered, avoiding sea grass and having carried out surveys beforehand, and using spud legs, not anchors.

The sand used may contain infauna, like worms and molluscs, some of which is killed in the process, although this is not considered to be a problem.

The hole formed, which can be up to four metres deepest, is already being filled, Mallia says, and will be completely refilled in a few months.

Mallia argues that minimal environmental damage takes place during re-nourishment works and that a far larger problem is all the plastic, bottles and rubbish found on the seabed. Several ecology reports are also drawn up to monitor the situation.