With regret, this month’s article will be the last in this series, at least for the time being. I am instead planning to focus any spare time on a new project, which involves extensive research about a major aspect of our nation’s heritage, which over recent years has been severely endangered largely due to a lack of knowledge, and subsequent complacency. As a form of transition, as it were, I have decided to conclude these six lost landmark appreciations by treating something related to my selected topic of upcoming study, that is, Malta’s lost gardens.

A glean through an 18th century cabreo at the National Library or an ordnance survey sheet at the Public Works Department will reveal a remarkable richness in the proportions and sheer amount of gardens that once greened Malta’s urban areas. Simply looking at Sliema for instance renders such a notion almost indigestible.

.jpg)

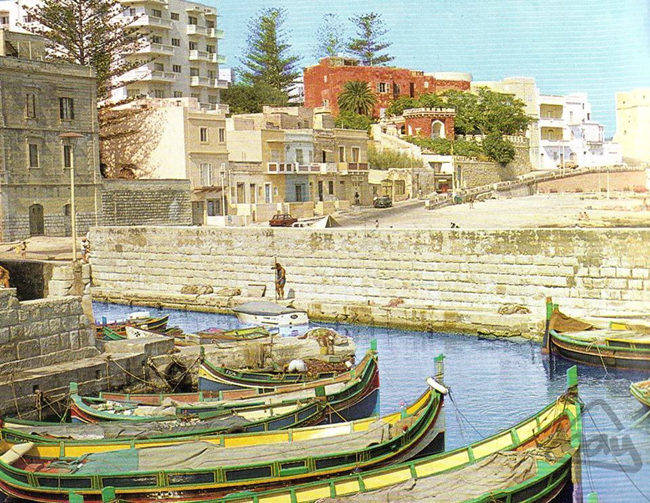

Gnien is-Sultan, Valletta (Courtesy Richard Ellis Collection)

To understand the historical development of Maltese garden architecture is key in grasping the distinct characteristics originating from various foreign influences, forming a precious and alas decimated vernacular. Gazetteering these gardens or delving into any form of detailed discussion is at this time impossible however I will attempt to give an overview of a few select sites that have either totally disappeared or of which only fragments survive.

An old postcard showing the distinctive red Villa Sant Cassia, St Paul's Bay surrounded by mature palms and aurecarias

Various maps of the Grand Harbour area prominently mark a walled garden at what is known today as Jesuit’s Hill. Giovanni Francesco Abela, the father of Maltese history, lived here and set up the first known museum through his collection of countless artefacts dating from antiquity and displaying them in what was later known as the Marsa Hortus.

As we all know, the military and utilitarian exigencies for which the Valletta was built left little consideration for greenery. In time as Baroque trends slipped into fashion, and as water became more abundant particularly after the installation of Wignacourt’s aqueduct, there was a yearning to soften the chivalrous solemnity of De Valette’s fortress city. In the 1640s a most luscious garden was built by Grandmaster Lascaris as part of a major infrastructural reorganisation of the Marina area. Known to all as Gnien is-Sultan, it consisted of a series discreet pathways leading from an elegant portal by what is today Victoria Gate towards the bulwark supporting the Upper Barracca Garden. Along the way lay ornate eye-catchers such as fountains and basins shaded in cypresses and pines. This was a welcome sight to those arriving for the first time to Malta and overwhelmed by the initial lack of vegetation. Today all that remains of Lascaris’ pleasure ground is the, alas dry, niched fountain abutting Ta’ Liesse Church, the rest replaced by a government housing block.

The ornamental portal and walkway of Villa Zammit, Pieta (Courtesy Richard Ellis Collection)

One might not expect to find Naxxar’s Palazzo Parisio in this article. Indeed the gardens we know have recently been expertly restored. Few perhaps however realise that the settecento garden extended well beyond the present back gate with an avenue extending for a mile out into the countryside. In the 1960s the surroundings were irreversibly remodelled to house the Malta Trade Fair, now lying virtually abandoned. The fate of this landscape stills hangs in the balance.

Sliema has lost so much in the way of gardens. When naming a few prominent examples Capua Palace springs to mind with its parterres, plinthed vases, trellises and aurecarias, all but lost in post-war years. Villa Bonici of which although a substantial part still survives and is happily earmarked for restoration, has sadly lost its distinct arcaded wall that stood along The Strand. Together with a good portion of the lower terraces this was demolished in the 1960s to make way for apartments. A lesser known stately residence was Villa Paradiso in Victoria Terrace which boasted a garden designed along a cruciform arrangement, complete with prospettivo, flattened in 1987.

Although unique in their own ways, one can begin to follow a general pattern and hallmark features of Maltese gardens. Walled terraces, raised gridiron pathways, citrus groves, prospettive, statuary, vases and troughs to name a few. Sometimes existing fields were incorporated to provide more terraces and groves giving the estates a somewhat bucolic flavour such as the Cassar Torregiani villa in Balluta which until recently stretched up to Ta’Giorni. Villa Siggiewi standing on St Nicholas Square boasted a series of citrus groves protected by high walls and sustained by an intricate irrigation system. Dominating this estate was a lofty walkway which culminated in an elliptical belvedere commanding spectacular views of southern Malta. Most of this now has vanished.

It is however in Pieta’ where I would like to conclude this piece. Even during the times of the Hospitallers this quiet promontory was regarded as an idyllic and convenient country retreat. By the early British period Pieta’ boasted two estates built within a few years of each other that encapsulated the essence of Maltese garden design in exceptionally contrasting ways. Villa Zammit had a predictable hierarchy of terraces not unlike Sliema’s Villa Bonici, with an emphasis on formality, linearity and symmetry. Its graceful gateway facing the sleepy beach stood as its most prominent feature. On the other side of the little village however something totally unseen in Malta had developed. This was John Hookham Frere’s attempt at a Mediterranean English landscape garden where surprise, asymmetry, poetry and mythology inspired its design. So peculiar was this landscape that three queens visiting the island specifically asked to tour the grounds. In 1930 Country Life Magazine carried a beautifully illustrated appreciation about it. To quote the author: “An unpretentious house facing the waters....That is one’s first views of the Villa Frere, and it is difficult to imagine that so much beauty lies behind it ... Once through the front door and out at the back ... it is an upward pilgrimage of beauty ...”

Of Villa Zammit, nothing remains whilst Villa Frere’s thirteen tumoli were since the 1950s reduced to a pitiful four.

Of course, as with buildings, the destruction of gardens still carries on. It is thanks to entities like Flimkien Ghall-Ambjent Ahjar, Din l-Art Helwa, various local councils and even the timely interjections of Mepa officials that gardens such as Villa Mekrech in Ghaxaq have been saved from the bulldozer’s teeth. Threats however still loom and one of the more effective defences is to fill in the gaping lacuna of knowledge on this fascinating facet of Maltese architectural and ecological history.