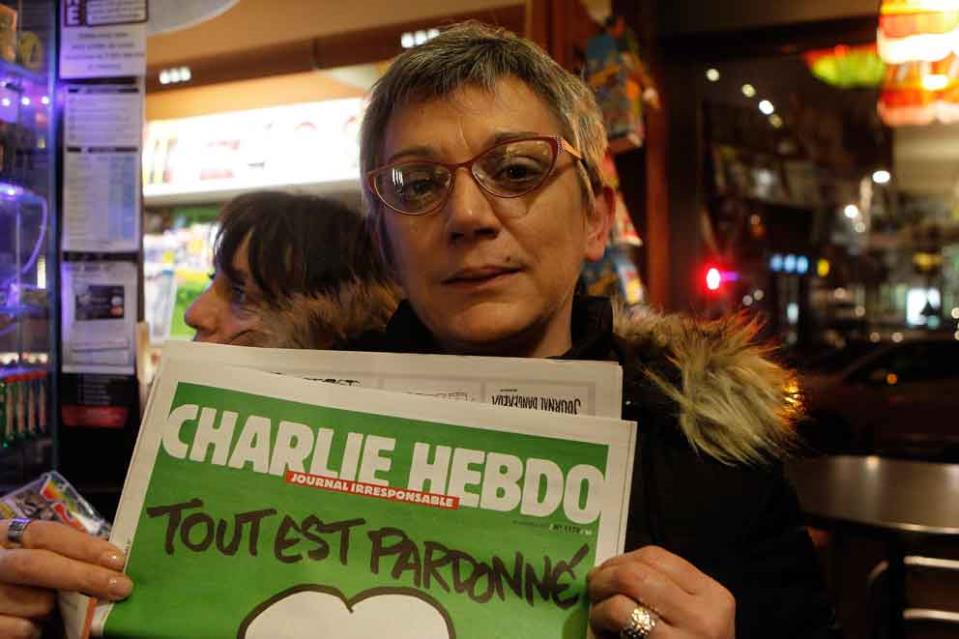

Malta may have joined much of the world in expressing solidarity with the victims of the attack on the offices of French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo last month, with Prime Minister Joseph Muscat heading off to Paris to participate in a unity rally.

However, it would actually be illegal to acquire or distribute many issues of the French magazine in Malta, under anti-blasphemy laws which are a rarity in Europe, the enforcement of which is even rarer.

Uttering any obscene words - although what constitutes obscene words is not defined - in public is one of the contraventions affecting public order included in Article 338 of the Criminal Code. But Article 342 sets out that if the act involves blasphemous words or expressions, the offender may be jailed for up to three months, although a fine of not less than €11.65 may be levied instead.

Another contravention listed in Article 338 includes "ecclesiastical habits or vestments" among the uniforms which cannot be worn without the permission of the authorities.

However, the Criminal Code also includes three articles which specifically address "crimes against the religious sentiment."

Article 163 and 164 concern the vilification of religion, granting a privileged position to the Roman Catholic religion - declared to be Malta's religion in the Constitution - in the process.

Article 163 sets out that whoever "publicly vilifies the Roman Catholic Apostolic Religion which is the religion of Malta, or gives offence to the Roman Catholic Apostolic Religion by vilifying those who profess such religion or its ministers, or anything which forms the object of, or is consecrated to, or is necessarily destined for Roman Catholic worship, shall, on conviction, be liable to imprisonment for a term from one to six months." Article 164 criminalises the same behaviour when directed towards "any cult tolerated by law," but in this case, only a maximum jail term of three months is foreseen.

Article 165 criminalises the obstruction of religious services, this time making no distinction between Roman Catholic services and those of other religions tolerated by law. Anyone who obstructs religious services carried out "with the assistance of a minister of religion or in any place of worship or in any public place or place open to the public" may be jailed for up to one year, or up to two years if the obstruction involves threats or violence.

A Maltese Charlie Hebdo would clearly fall foul of both Article 163 - the cover of one issue, for instance, carried a depiction of the Trinity engaged in a sexual act - and Article 164.

Due to some of the magazine's more risqué content, anyone involved in its production or distribution could also be prosecuted under Article 208, which criminalises the production, acquisition or distribution of obscene or pornographic material, with offenders liable to imprisonment for up to 1 year.

Articles 163-165 of the Criminal Code date back to 1933, and have not been amended since.

A number of laws deemed to be obsolete - including laws such as the Carrier-Pigeons Ordinance and the Distribution of German Enemy Property Ordinance - are set for repeal by parliament shortly.

But blasphemy laws have not been considered for inclusion in that list, perhaps because they are not yet deemed to be obsolete. At least as far as the Roman Catholic religion is concerned, blasphemy laws are still actively enforced, and a number of people have received suspended jail terms as a result.

A number of people had ended up in Court and charged with vilifying the Roman Catholic religion in the wake of the 2009 Nadur carnival. Then-Archbishop of Malta, Paul Cremona, and Gozo Bishop Mario Grech had jointly urged the authorities to intervene before the police confirmed that arraignments would take place.

A 26-year-old man who dressed up as Jesus received a one-month jail term suspended for six months after pleading guilty. But a group who dressed up as nuns pleaded not guilty and were acquitted because they were not wearing any religious symbols.

However, another young man received a suspended jail term for vilifying the Roman Catholic religion in 2009: he displayed visuals which included, among other things, Pope John Paul II and a naked woman while DJing at a music festival.

Which laws should go?

On first glance, the provision that appears to be most justifiable is Article 165, as preventing the obstruction of religious services can help guarantee people's right to practice their faith freely.

That using threats or violence to disrupt religious services should be a criminal offence is perhaps indisputable, and such a provision could also be required in cases of organised disruptions clearly aimed at preventing members of a particular religion from practising their faith peacefully.

But as it stands, the article can be applied in an overzealous manner, as may have been the case just last summer, when a 28-year-old German woman was arrested in Sliema after dancing next to a band while wearing a bikini - she had just returned from a boat party - during the Stella Maris feast. She was held in custody overnight before being fined and conditionally discharged.

In such cases, lesser contraventions such as breaching the public peace should suffice, and arresting a non-violent offender over such a case is clearly excessive. Such cases should arguably not even make it to court at all, as discretion could easily be applied: the same discretion applied during countless village feasts when supporters of a particular band club or saint hurl obscene insults at their rivals in the presence of various police officers.

Whether uttering obscene words in public should remain a contravention is arguable - the list of contraventions against public order includes other relatively minor acts, including importuning people to advertise or sell a product, or people over 15 years of age using playing equipment at children's playgrounds - but there is little to justify the possible imprisonment of someone who simply utters blasphemous words, although such a punishment does not appear to have been applied for some time.

But the provisions whose justification appears to be most tenuous - particularly in the wake of Malta's reaction to the Charlie Hebdo attack - are the articles criminalising the vilification of religion.

The freedom to offend

The provisions undermine the concept of freedom of expression, which would also include, to some extent, the freedom to offend.

Of course, there are other limitations to expression: incitement or instigation to commit a crime is a crime in itself, for instance.

In fact, the provisions were introduced a year after the end of Gerald Strickland's term as Prime Minister of Malta, a term marked by a clash with the ecclesiastic authorities, which declared that people who voted for his party were committing a mortal sin, and by an attempt on his life.

But such a scenario is highly unlikely to repeat itself, so what is left is to determine how much people can be allowed to offend others.

In his own remarks following the Charlie Hebdo tragedy, Pope Francis said that people should not provoke and insult the faith of others, stating that if his friend says a curse word against his mother, he could expect a punch.

However, such provocation would be taken into consideration in court if a verbal argument escalates into a physical one.

Beyond such considerations, taking care not to offend others ultimately boils down to politeness and respect. While such behaviour may be commended, it is not legally enforced, and neither should it be.

On the other hand, Articles 163 and 164 would not be the only provisions that should be struck down if the freedom to expression is to be considered as comprising the freedom to offend.

For instance, Article 72 of the Criminal Code states that whoever uses "any defamatory, insulting, or disparaging words, acts or gestures in contempt of the person of the President of Malta" can be jailed for up to three months, effectively Malta's own version of a lèse-majesté law.