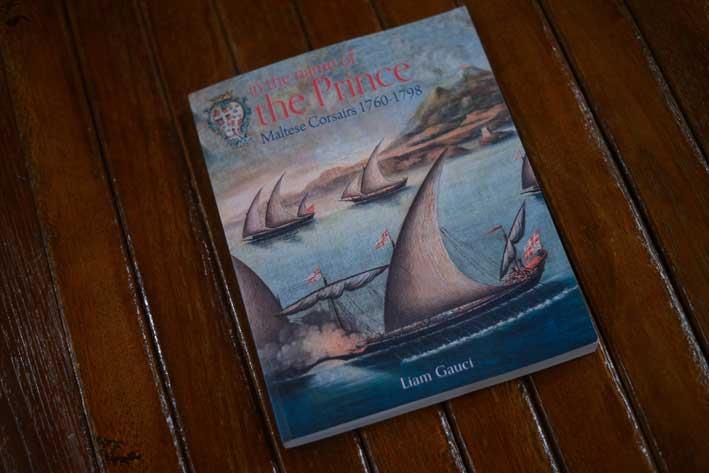

In history lessons in school, we learnt that the Knights of St John were a religious order that helped keep the Ottoman Empire at bay; who built fortifications which were the envy of the Mediterranean; and who made Malta a hub of enterprise in Europe. But what do we know what the common people in the street actually did to earn a living? This is what Liam Gauci, curator for the Malta Maritime Museum, set out to do with his book In the name of the Prince: Maltese Corsairs 1760-1798.

This book is the first of its kind not only for Heritage Malta, which published the book, but also for the world. In order to compile all the necessary information, Mr Gauci had to go through archives which had never been catalogued and thus were untouched and completely unknown. The author researched each of the 2,000 people who lived at the time one by one and who were all involved directly and indirectly in the world of corsairing. Regarding the large number of records, Mr Gauci quipped, “We are very lucky the knights were so bureaucratic. I can now tell you how much it cost a captain to get from his home to his ship, or how much it cost him to buy flowers to bless the ship.”

What is corsairing? Essentially, as much as Mr Gauci insisted he not want to draw comparisons, corsairs were pretty much high class pirates. The difference between piracy and corsairing was that to be a corsair one had to have an official title within a legal framework. One had to live and work within a set of laws and rights and held accountable for one’s actions at all times.

The author explained, “It was a legal job and the conclusion I came to was that when the Knights left, the same guy who had a ship called Santissima Krocifisso painted over the name, called it Legalitee to attack the British, then painted over it again when the British came and called it King George III, and then went on to attack the French. It was a way of life which predated the Knights and continued uninterrupted.

“They were mercenaries and their sole purpose was commerce raiding. You needed a merchant ship to make profit, not a warship. That’s where the cargo was, so that’s where the profit was. What was different was the ‘letters de course’ obtained from the Knights legalizing it within a framework of laws and was heavily taxed. That was not pirating, it was completely legal.

“You needed to get investors interested in your venture. If you were a good captain, people would flock to invest in you. In fact, there were captains who concocted schemes saying they had contact with spirits to tell them where the treasure was. These people who resorted to tricks and schemes were actually taken to court. One such person was Stefano Raffaeli.

“It was all about licensing and needing investors to buy a boat, rent arms from the Order, buy provisions or get investment in kind, and then choosing a crew who you had to pay. The crew had rights and could actually take you to court. Almost like a form of a union.

“Pirating was a desperate act. This was completely controlled and you needed skill, knowledge and money within the whole framework. I am trying to make the line a lot more distinct. All this was being done in the name of the Prince of Malta, the Grand Master.”

Mr Gauci went on to explain that the Grandmasters at the time were so obsessed with being sovereigns that they actually called themselves princes and kings of the island, rather than convent priors, which is what they technically were in the eyes of the Pope. Two quotes from the book explain this struggle between the knights and the Pope very concisely.

“In a few words, the Grand Master informed the Pope that a loophole existed within the system and he fully intended to use it, exercising his right as the Prince of Malta. This was the start of an intensified power struggle between Rome and Malta. It arose from the ironic situation of the Grand Master’s double role as a sovereign prince of a state while still remaining a de-facto Prior of a convent answerable to Rome and the Pope. It was a paradox which would never go away.”

“Geography and economics also played their part in this pantomime. Rome was too far away from the convent in Malta. Malta was an island and its insularity created the mentality of a fiefdom, which was created intentionally by the Order. A religious order so sovereign that the convent minted its own currency. A sovereignty protected by a vast network of fortifications within which lay excellent harbours to protect a seaborne conglomeration of raiders. These raiders operated within a principality upheld by responsions coming from mainland Europe. A Europe duped into believing that the Prince of Malta was the defender of Catholic Europe and Malta was the centre for schooling the future admirals of European fleets. This was the Malta created by the Order of St John.”

At this point, if Malta wasn’t the capital of Christian corsairs, it was very close. This community of people living in Malta essentially had the potential to upset the entire balance of power in the Mediterranean. One of the people who almost did just that was Pietro Zelalich.

He was a man from Montenegro who was a slave of the Ottoman Sultans. The slave one day enlisted the help of his contacts in Turkey and captured a ship that was internationally renowned as one of the greatest testaments to the Ottoman Empire and the power of the Sultans. He then sailed the ship to Malta where he was allowed to dock.

As a result, the Ottomans declared war against Malta, and it was such a threat to the entire economic balance of the Mediterranean, that the French actually bought the ship from the Knights and gave it back to the Ottomans in order to continue with their merchandise routes which would have been totally disrupted by the ensuing conflict.

Zelalich was one of many notable character of the time. He was a notorious blasphemer, constantly speaking of how he wished he were back in Turkey, giving praise to Muhammad and claiming that if he weren’t so old, he would have converted to Islam seven times over. He was also accused of sodomy and of showing public affection to one of his sailors. Mr Gauci explained: “It was regarded by the British navy with disgust and if clear proof was found, you were hanged. In the Mediterranean, people were left to their own devices. They cared more that he swore and wanted to go back to Turkey.”

Another character was Guillermo Lorenzi. This captain is a perfect example of the misconception that corsairing was basically ‘high-class piracy’. Lorenzi had utensils in his house made entirely of solid silver, as well as a pet parrot as a symbol of affluence. It was such an awe-inspiring thing at the time because apart from importing the parrot from South America, its maintenance cost a pretty penny, making it a sort of status symbol comparable to buying an extortionately priced luxury car with over the top extra commodities today.

Another Montenegrin, Giorgio Mitrovich, who also worked and married in Malta was responsible for a whole generation of corsairs from the island. His historical significance is particularly important because if it weren’t for him, or more specifically one of his grandchildren, there wouldn’t have been newspapers in Malta at that time.

Speaking about Malta’s status as a cosmopolitan island at the time, and as far back as the 11th century, Mr Gauci told The Malta Independent on Sunday: “I have studied 2000 individual sailors, and I can presume that there might have been double that amount of corsairs. The majority were Sicilian, but there were also some from Gozo. There was a large concentration of foreigners in Senglea. There were people from Birkirkara and Siggiewi as well. The whole island was directly and indirectly involved in the industry. The British stopped it in the 1820s. The earliest instant that I know of was in the 1400s, however I know there are much earlier. One interesting thing is that as long as there were slaves in Malta, there were corsairs. Slaves were the most important profit makers. Slavery started most probably in the 11th century.”

We couldn’t resist asking questions directly related to piracy; such as the role of women at the time or the whole concept of raping and pillaging. Mr Gauci responded with a grin saying, “While writing, I saw a lot of black sails and it is very difficult to find certain information.” It was also pointed out that this could be because many of the facts just weren’t reported or were skilfully hidden from the public.

“The role of women was of investors. The wives of captains would have their dowry invested in the ship and, according to Maltese law at the time, one could never touch the dowry. If you were sued by a Greek and had to pay compensation, instead of losing everything you would tell them your wife invested her dowry in the ship. It was essentially loophole after loophole. Even in terms of tax evasion.

“There were very few cases of rape and pillaging, probably because they are hidden. We have one example of them going to an island in Greece and, as quoted in the book, ‘He, the sailor on land, will then follow the dictations of passions and appetites, let them lead him whither they may. As bad as things might have been at sea, they seem to have been worse in port.’

“One must keep in mind that many of the crew members were prisoners who even used to escape, especially the lower ranking ones. There is a documented instance that in one of the smaller Greek islands they first ran after Greek women, then they plundered the land, and after that a crew of 30 people ate two cows and five lambs without paying. There was also another instance of a huge amount of pillaging in Gozo.”

After the clear amount of research and hard work that went into writing this book, there were two questions that needed to be answered. Why did Liam Gauci embark on this long journey when he was 20 and publishing the book now that he is 30? And also, are there things that he can clearly say are purely myth?

In answer to the first question, “It was a question of wanting to learn who the people in Malta were. I mean it is interesting to know about the Grand Masters, but what were the opportunities for the common people. So I said let’s sit down and see who these corsairs were. Who were their wives? What food did they eat? Were they drinking wine and beer? Turns out it was a lot of rum, grappa and wine. I wanted to look at history from another angle. It is very important to look at history from below because you see those little details, and once they are repeated you see the bigger picture. I also used to love watching Errol Flynn movies as a child.”

In answer to the question about what can be confirmed as myth, Liam said: “It was not an easy way of life. I think we would find it very difficult to live the life they lived. Ships were out at sea for months on end and you mostly lived on deck. If you broke a rule on board, you were whipped. You suffered hunger. We tend to romanticise a little too much, obviously due to films and books, although a lot of it is actually true. The idea of buried treasure is 99 per cent false although technically Lorenzi did bury his fortune, but it was found by his executioners.”

One thing that Liam Gauci wants to make clear about the time period is: “There was a community of people living in Malta who were not the Knights, the French or the British. They were Maltese and foreigners trying to make a living in Malta, and one of their livelihoods was corsairing.”

The book was published by Heritage Malta and sponsored by Lombard Bank with Daniel Cilia responsible for the design. The book’s launch will be held on 24 February at 7pm at the Malta Maritime Museum.