One of the battles that the LGBTIQ+ community commemorates and highlights during pride month is the one against phobias that are exhibited towards its members by heteronormative perspectives.

However, it should be noted that these phobias exist in the community itself since heteronormativity is prevalent in most societies worldwide, which leads to the internalisation of certain customs that block understanding of anything beyond them.

The Malta Independent on Sunday spoke with the Psychotherapist Ray Micallef to get a better grasp on the origins of internalised phobia and its occurrence among LGBTIQ+ persons.

Where does the internalisation of certain ideologies come from, and what effects does it have on those impacted by it?

“Internalised phobia originates in a hetero-normative society, where heterosexuality is promoted as the norm or the preferred way of being. We internalise these messages from our environment at a very young age and we grow up with them,” Micallef explained.

These messages are very subtle, making it more difficult to be aware of one’s biases and prejudices because they are so deeply rooted.

In turn, LGBTIQ+ persons can grow up feeling flawed which causes a conflict between their actual sexual orientation or gender identity and what they present to others (or themselves even) in order to feel safe and accepted in a straight culture.

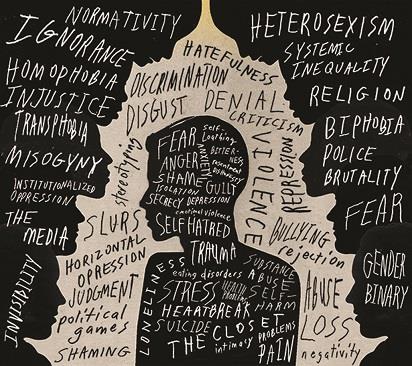

Micallef said that internalised phobia can manifest in many different mental health issues, such as depression, isolation, addictions, guilt and the most crippling of emotions; shame.

“Shame can be very toxic. It is something I always come across in some form with the vast majority of gay clients in my practice. Shame is a feeling that ‘something is fundamentally wrong with me’ which makes one want to hide and/or disappear.”

How does internalisation affect the way one interacts with or acts around others, or even one’s own view of themselves?

“As so often happens, the way people are externally treated by others may become the way they internally treat themselves. So, when society sees the LGBTIQ+ persons as bad and defective, this is how these people may view themselves.”

This can develop a negative self-image based on social shame and personal guilt which eats away at one’s personal identity and capacity for intimacy. In order to deal with all this, LGBTIQ+ persons may become withdrawn or strive for power and control to the point of perfectionism. “This is why so many excel at what they do, such as gay men in the world of fashion, but still may feel not good enough in whatever they achieve, leaving them feeling empty.”

Micallef explained that he has come across a spectrum of issues in therapy which, when externalised, can actually pose significant danger to oneself and others. Such strategies are used to temporarily relieve the painful feelings of inadequacy, inferiority and unlovability that many people on the LGBTIQ+ spectrum frequently struggle with. A general sense of personal worth and a positive view of one’s sexual orientation are critical for one’s mental health.

He acknowledged that there has been an enormous shift in most of the Western world toward recognising and legalising LGBTIQ+ rights, but internalised phobia is still pervasive.

One can observe instances of people who believe they are totally accepting and then act out or say something that stems from their internalized beliefs – “we all have our prejudices and biases, gay or straight.”

Additionally, Malta’s culture tends to value masculine ideals over feminine ones and there are masculine men who feel threatened by homosexuality, since it feels like a betrayal of masculinity, and may become actively violent against LGBTIQ+ persons.

“Maybe we can narrow the saying ‘it’s a man’s world’ to ‘it’s a straight man’s world’.”

Where do you think internalised homophobia within the LGBTIQ+ community comes from? Do stereotypes play a role here?

“Again, the root is in the internalised phobia which comes from gender stereotypes,” Micallef said. “Society presents stereotypes of masculinity and femininity. So, the masculine gay man who has internalised the stereotype and who does not want to appear gay, may shun a trans or another man who is stereotyped as effeminate in order to preserve his own self-image of a masculine man.”

Associating with those who do not fit the masculine ideal may trigger his shame, which can be attributed to hearing pejorative labels such as ‘sissy’ for men who appear effeminate or comments like ‘don’t act so gay’ over how one talks, gestures, sits and moves.

In turn, the masculine gay man may even blame effeminate men or trans for society’s biases and prejudices as they fall short of masculine ideals and even cause them to engage in homophobic behaviours like ridicule, harassment, verbal or even physical attacks.

Why do you think it is difficult for someone who has experienced similar judgment based on their sexuality or gender, to accept someone else’s story or perspective?

Micallef said that people react differently to this issue as some might act out of fear in certain environments, like cultures that eschew homosexuality completely and fear for safety predominates. So, in order to feel secure, they hide or deny their sexuality.

“Because of the internalisation process which we have been talking about, there are those who may need to deny or totally reject their sexuality in order to psychologically defend themselves.”

In turn, they may adopt a variety of mechanisms like denial and projection to ward off any threat of being perceived by others, maybe even by themselves, as gay. One example would be projecting one’s self-hatred by translating their denial into hate towards other gay persons.

Micallef also mentioned an interesting mechanism adapted by such persons known as Reaction Formation wherein one cannot accept the feeling of love for another man (straight or gay) and turns it into the opposite; hate.

“This of course brings much turmoil for the persons concerned but it is at the severe end of the Internalised Phobia spectrum. People who resist, or completely refuse, identifying as LGBTIQ+, are unable to understand their own negative feelings and the resulting consequences.”

What can one do to overcome their internalised phobias, especially in this context?

“Talking to an empathic therapist who is skilled in this area will help to change these internalised beliefs attributed to rejection and shame into self-acceptance, compassion, tolerance and understanding,” Micallef said, suggesting psychotherapy as a beneficial option.

On a more individual level, he advised reflecting on how one’s internalised phobias impacted their lives, instead of rejecting it. Getting informed by reading moving and inspiring stories of similar people will help increase one’s knowledge on the topic. Mindfulness is also a great practice to get more in touch and aware of oneself by examining one’s own judgements, both towards self and others, and trying to find out their origins.

It is also important to find support from others, not only from the LGBTIQ+ community but also from outside as understanding and acceptance can be very healing. Moving away from toxic influences may be difficult as it can come from family, friends, neighbours and colleagues. “I may also add the notion of religion because if the doctrine one follows is perpetually in conflict with one’s identity, it may be more damaging than rewarding.”

Micallef added that coming out is very important to consider if one feels safe enough since, even though it might feel like a painful process, it can be very healing.

“Finally, I would say to those suffering from this condition to please know that you are not sick or bad or immoral. This is what a prejudiced, heterosexist culture has made you believe. You do not need to be cured. Try to be honest with your emotions, talk to understanding others who can validate you as you are.”