It’s difficult to think that a humble, unassuming red-brick single-storey building across New York’s East River can provide a home away from home.

Yet, the Maltese flag fluttering outside the Maltese Centre in Astoria and the eight-pointed crosses emblazoned on its sign already provides a taste of home in the hustle and bustle of the city that never sleeps.

“Members Only”, the door says, but The Malta Independent is greeted by the call of “idhol, idhol!” [come in, come in!] as the first few, tentative steps into the building are taken. The social club – the only one for the Maltese community in New York City – truly is more like a kazin (club), which wouldn’t be out of place in a Maltese village, than an establishment synonymous with the United States.

Established in 1979 and opened in Astoria in 1982 by then Foreign Minister Alex Sciberras Trigona, the Maltese Centre works to provide a space where the Maltese community can gather, and also provides means of preserving the Maltese language and culture.

From left to right: Angelo Abela, Carmelo Mompalao, Gino Fenech, Larry Muscat, and John Bajada

It’s a Sunday when The Malta Independent walks through the door into the club. A covered-up pool table takes up the entrance space, with a bar area further back. Plaques of every locality in Malta and Gozo line the walls. It’s a slow day, but five men still sit around a table loudly discussing their consternation with inflation and the rise in every day prices. Sometimes it doesn’t take much to feel like home.

Angelo Abela, Carmelo Mompalao, John Bajada, Larry Muscat and Gino Fenech spend the best part of the next hour-and-a-half regaling stories of why they left Malta, of how they’ve established their lives in the Big Apple and of what it’s like living in the United States.

All Gozitans except for Gino, who the others joke is a Gozitan from Mellieha, Angelo was the first to leave Malta, coming to New York City at the age of 16 in 1967. Larry arrived soon after in 1970, while Gino, John and Carmelo arrived in the Big Apple in 1979, 1981, and 1984 respectively.

“I only came here for two years,” Carmelo says with a smile. “It took me two years to get used to it, then I figured I’d spend another three years and then that became 39 years,” he continues.

It’s a similar theme across the table: Angelo and John too say that they initially came for a couple of years but eventually just decided to stay in New York City.

Perhaps an exception is Gino: “My wife had a Green Card and we chose to emigrate here,” he recalls, adding that none of his family followed him here, though his wife’s did.

Family is a significant theme across the discussion: it is what keeps them all in New York City, but it is also what almost all of them miss the most from Malta.

All five of the group are married and have children and grandchildren who were born and who live in the United States, but when asked what they missed the most about Malta, it is family which is the answer.

John, for instance, immediately answers that what – or rather, who – he misses most from Malta is his 93-year-old mother, while Carmelo likewise answers that it is his sister whom he misses most. Gino’s side of the family did not emigrate, and Larry’s siblings – he came from a family of 10 – are also all still in Malta, though he admits that social media today has made it far easier for him to keep in touch with them.

But America to them remains their home base. For all of them it provided opportunities which would scarcely have been found in the Malta and Gozo that they left decades ago.

Drawing a comparison, Carmelo says that when he left a colour-TV was prohibitively expensive in Malta and there was a waiting list for it; whereas in New York all it took was one salary to purchase one. “There were – and still are – a lot of opportunities for those who work hard,” he says.

Larry is more pensive about the matter: he describes America as a “land of extremes”, saying that you can see some achieve extreme riches but others in extreme poverty. The riches are so extreme, Carmelo chimes in, that the rich wouldn’t even be bothered with you if you had to make some good money for yourself.

As the discussion continues and another tray of tea (and a couple of beers, despite the fact that it is a Sunday afternoon) is brought to the table, it’s pertinent to note that it is the Maltese language which dominates the inner walls of this building. English is used only sparingly to make up a sentence here and here.

“When we speak about contraband we speak in Maltese,” Carmelo jokes, when the use of the language so seamlessly is pointed out. “You never forget your mother tongue… we speak to our children mostly in English, but between us it’s remained the same,” Larry continues.

It’s clear that Malta does live on in their minds, even though the group are all established in New York City. All of them visit the country, sometimes for months at a time, practically every year, and all of them share a few of the smaller things which they enjoy.

For Carmelo, it’s the sea and the village feasts. For John, it’s taking part in the Holy Week celebrations in Easter and attending the feast in Xaghra. For Angelo, it’s going out trapping and going for a swim at Dahlet Qorrot.

John perhaps describes it best: “I came here when I was young and ended up staying for 42 years, but I’ve been to Malta a million times since; Malta is like my mother, and New York is like my father, but I’ll keep going back to Malta until I remain alive.”

As the discussion continues, Gino, who has been the quietest out of the five, at a point opens an invitation to a downstairs hall.

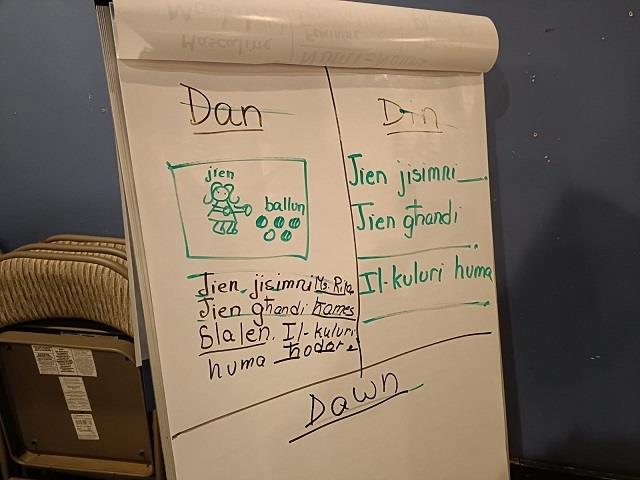

The Centre uses this area for activities such as to run Maltese language classes every two to three weeks. It’s an expansive space: a large table dominates the run, with a flipboard containing elements of the most recent Maltese lesson. Verb conjugation appears to have been the topic of the day.

Gino, who is the vice-president of the Maltese Centre and who has been one of the volunteers keeping things going for the last 15 years, explains that lessons are delivered by a Maltese teacher who lives and works in Brooklyn.

It’s all part of an effort to keep the Maltese language alive down the generations. “We speak to my children in Maltese even though they were born here and they can understand everything… they can understand more than I’d want, being honest,” Gino chuckles.

“But for them to actually speak Maltese and write it, it’s difficult,” he adds.

Standing out in the room is also a statue of St Paul in the corner. It’s just over a week after the feast of St Paul when The Malta Independent visits the Centre and the statue is still in place after a commemorative mass was held.

“We have a priest from Rabat, Gozo, who celebrated it. We weren’t that many people as quite a few had other commitments, but we still try and keep things alive, and after we hold a sort of pasta night for the members to keep the community going,” Gino says.

The story of the statue itself is interesting: it was made in Gozo by the well-known sculptor and statuarian Agostino – known more commonly as Wistin – Camilleri and was then brought to New York City. Hailed as Gozo’s first artist, Camilleri died in 1979 and is today honoured with a statue in his hometown of Rabat.

This particular statute is made out of papier-mâché and, Gino says, previously resided in a church on 11th Street in New York City – an area which had a vibrant Maltese community. When the church closed down, the statue was brought to the Maltese Centre.

Beyond the lessons and the religious activities, the Centre organises a number of activities which act as fundraisers so that it can stay open. Barbeques are organised on the occasions of the feasts of l-Imnarja, Santa Marija and il-Vittorja, while other social events such as bingo nights and various parties are also organised. Just a day before this newspaper visited the centre in fact, a Carnival party was held.

“You meet people here who you wouldn’t meet otherwise,” Gino says, explaining the importance of the Centre. “I live on the East Side and I wouldn’t have known most of these people if it weren’t for here.”

“We do work really hard to keep the Centre going. We need around $50,000 a year to keep it going, and we only have around 150 members so the activities are what’s most important for us,” he continues.

He leads the way to an outside area: an open area which is used for barbeques in summer and an area adjacent to it sheltered by a white tent.

“They play bocci here,” Gino explains, as shouts emanate from inside the tent, showing that a game is in fact going on in that moment.

A group of six men provide ample welcome as the tent door opens. Like the group upstairs, all of them bar one are Gozitan: four are from Ghajnsielem, one is from Zebbug. The one Maltese man of the group is from Gzira.

Metal balls – striped and solid – are used to play the game, with a radio antenna being extended as necessary in order to clear up any disputes over which ball is closer to the jack.

It’s a scene of typical Maltese banter: one team chides the other as they hold the lead and shouts of praise – or colourful consternation – greet a good or bad throw.

“You always wanted to be in a video, Leli!,” one shouts as a means of encouragement to another.

It truly feels like what the Centre aims to be: a piece of home.