Searching fervently for a missing 6-year-old boy named Etan Patz, police jotted a teenage shop worker's name among those of many people they met, never expecting the clerk would become their suspect more than three decades later.

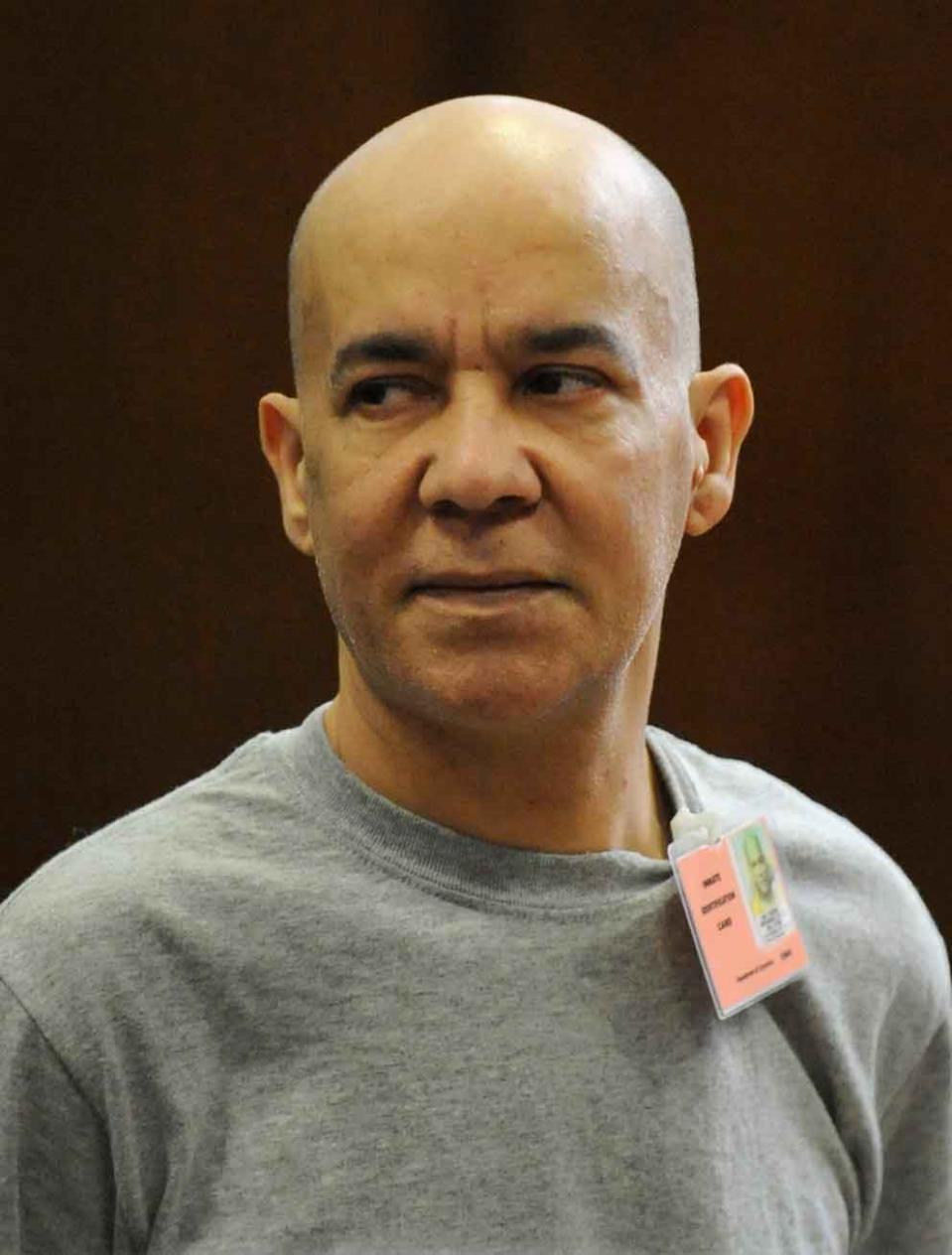

But after 35 years, Pedro Hernandez is going on trial in a murder and kidnapping case that shaped the nation's approach to missing children. Opening statements are set for Friday.

Hernandez emerged as a suspect in 2012, based on a tip and a videotaped confession that prosecutors say was foreshadowed by remarks he made to friends and relatives in the 1980s. His defense hinges on convincing jurors that the confession is false, along with suggesting that the real killer may be a convicted Pennsylvania child molester who was a prime suspect for years.

(The boy's mother Julie)

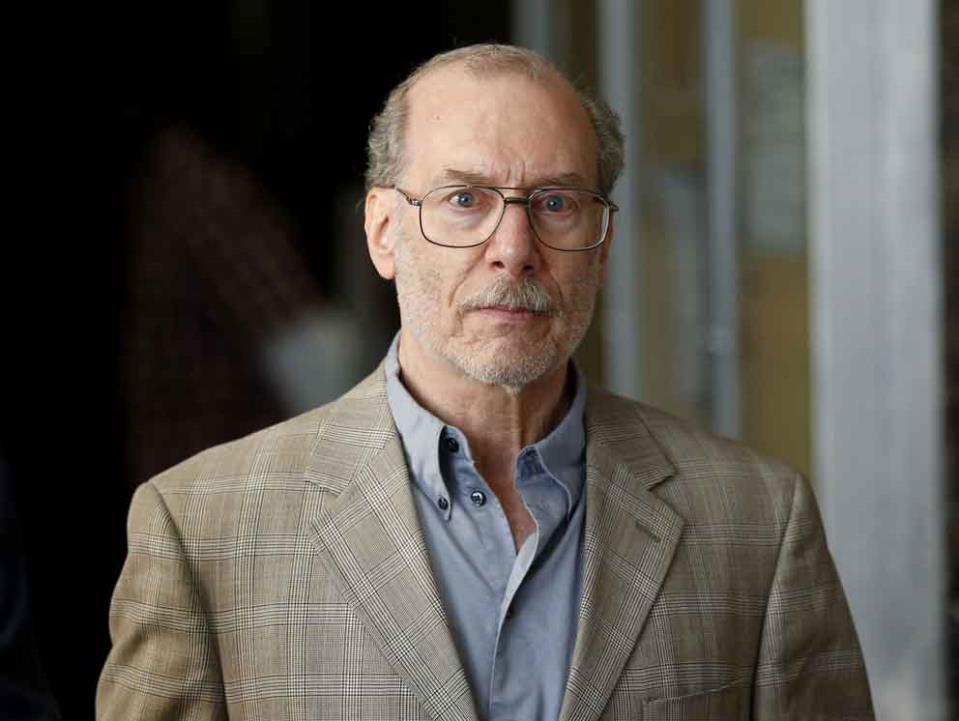

"It will be, I think, an extremely interesting case," state Supreme Court Justice Maxwell Wiley told prospective jurors earlier this month, adding that those chosen would be in for "an experience they'll never forget."

In considering evidence that reaches back to 1979, jurors will delve into a missing child case that helped inject a new protectiveness into American parenting. Last seen walking alone to his school bus stop, Etan became one of the first missing children featured on milk cartons. His parents helped advocate for legislation that created a nationwide law-enforcement framework to address such cases, and the anniversary of his disappearance became National Missing Children's Day.

The trial is expected to last up to three months and feature witnesses including Etan's mother, psychologists, an inmate informant who knows Hernandez, and possibly other informants testifying against the earlier suspect.

The seven-man, five-woman jury was chosen from a pool of about 700 people. Some openly wondered about bringing a case to trial after so many years.

(The boy's father Stan)

"A lot of time has elapsed, and a lot of things have probably changed. ... It's 35-year-old memories," one man said during questioning earlier this week. He was not selected.

Prosecutors have spotlighted Hernandez's videotaped, hours-long confessions, in which he says he offered Etan a soda to entice him into the basement of the Manhattan convenience store where Hernandez worked. Then, Hernandez said, he choked the boy and dumped him, still alive, in a box with some curbside trash. Etan's body has never been found.

"Something just took over me, and I was just choking him," said Hernandez, 54, of Maple Shade, New Jersey. "He just kind of stood there, and I just felt bad, what I did."

Defense lawyers say Hernandez' confession is fiction, dreamed up by a mentally ill man with a low IQ and a history of hallucinations - and fueled by over six hours of police questioning before Hernandez was read his rights.

After confessing, Hernandez told a defense psychologist his memory of the killing "feels like a dream" and he wasn't sure it had really happened.

(The Patz couple at the time of their son's disappearance)

"You've heard the term 'false confession?'" defense lawyer Harvey Fishbein asked during jury questioning this week.

False confessions happen - sometimes in cases as notorious as the killing of child beauty pageant star JonBenet Ramsey - but they are hard to quantify. They factor in about 15 to 25 percent of known cases that ended in exonerations, said Allison Redlich, a University of Albany criminal justice professor.

A defense psychologist wrote that Hernandez's psychological problems and intellectual limitations make him more likely than other people to confess falsely. Prosecutors dispute that conclusion and call the confession credible.

Hernandez's lawyers also plan to point to longtime suspect Jose Ramos, a Pennsylvania prisoner who dated a woman who sometimes cared for Etan. Authorities said Ramos made incriminating statements when questioned about Etan in the 1980s, though he never confessed to killing the boy. Ramos has denied it, but a civil court found him liable for Etan's death in 2004 after Ramos stopped cooperating with questioning.

(The accused, Pedro Hernandez)

AP EXPLAINS: The case of Etan Patz, who disappeared in 1979

The 1979 disappearance of Etan Patz helped catalyze a national missing-children's movement. Six-year-old Etan was one of the first vanished children whose case was publicized in what became a high-profile way: on milk cartons. His disappearance also helped usher in an age of parental anxiety. On Friday, opening statements are set to be heard in the murder and kidnapping trial of Pedro Hernandez, who confessed in 2012. Here's a brief explanation of how Patz'sdisappearance and the ensuing murder case:

A YOUNG BOY VANISHES

Etan Patz was walking to his Manhattan school bus stop alone for the first time when he disappeared May 25, 1979, igniting an exhaustive search and helping to make missing children a national cause in the United States. The anniversary of his disappearance, May 25, became National Missing Children's Day. His parents helped press for new laws that established a national hotline and made it easier for law enforcement agencies to share information about missing children. The movement grew after the kidnapping and killing of 6-year-old Adam Walsh in 1981 in Florida and other high-profile child abductions. Frightened parents soon stopped letting children walk alone to school and play unsupervised in their neighborhoods.

___

AN INVESTIGATION SPANS CONTINENTS AND DECADES

Etan's body has never been found, but his family had him legally declared dead in 2001. The investigation stretched across decades and at one point reached Israel before police announced that Hernandez had confessed in May 2012. Then police got a tip shortly before the arrest of Pedro Hernandez, 54, of Maple Shade, New Jersey. He worked at a convenience store in Etan's neighborhood but had never been a suspect. Hernandez has pleaded not guilty. In his recorded confessions, Hernandez tranquilly recounts offering soda to entice Etan into the convenience store basement and choking him. He says he put the still-living boy into a plastic bag, boxed up the bag and left it on a street.

___

A LONG-AWAITED DAY IN COURT

Prosecutors' case appears to center on Hernandez's confessions to them and police, plus statements authorities say he made to a friend, his ex-wife and a church prayer group in the 1980s about having harmed a child in New York. The prosecution team hasn't alluded to any physical evidence against Hernandez, and his defense has said there is none. Hernandez's defense maintains his confessions are the false imaginings of a man who has an IQ in the lowest 2 percent of the population and has problems discerning reality from fiction. Prosecutors call the confessions credible, and Manhattan state Supreme Court Justice Maxwell Wiley ruled they could be used at trial. The decision followed a weekslong hearing on whether Hernandez was properly advised of his rights to stay silent and mentally capable of understanding them. Hernandez has taken anti-psychotic medication for years and has been diagnosed with schizotypal personality disorder, which includes the characteristics of social isolation and odd beliefs.

___

ANOTHER SUSPECT

The defense also wants jurors to consider longtime suspect Jose Ramos, a convicted Pennsylvania child molester. A civil court declared Ramos responsible for Etan's death after he rebuffed questioning, but he was never criminally charged and has denied involvement. Ramos has refused to testify at Hernandez's trial, saying he'd invoke his rights against self-incrimination, but some evidence about the investigation into Ramos will be allowed.