Gustav Holst's the Planets is easily one of the most notable and influential works of music written in the 20th century.

Its seven movements - each named after a planet in the solar system - convey a wide variety of emotions. The atmospheric nature of the work has inspired film scores, chief among them - perhaps unsurprisingly - those of science fiction films.

But the inspiration for the suite was not astronomical, but grounded in astrology, specifically on the effect the movement of the planets was believed to have on those living on Earth. For this reason, Earth is not depicted in the piece.

So ultimately, beyond Holst's own musical background, the work owes its existence to millennia of astrological beliefs, as well as a chance holiday which spurred the English composer's interest in the subject.

Wandering stars

While presently, astronomy is treated a proper science and astrology deemed to have no scientific validity, for much of their history, they were effectively different facets of the same academic subject.

Stars have long fascinated man, and numerous ancient cultures across the world have come up with detailed observations of the skies. Often, stars were divided into two categories. The vast majority maintained a constant relative position in the skies, even as they moved across them. Many cultures grouped these stars into constellations, although since these groupings were arbitrary, constellations varied from place to place.

But a handful of "stars" - among the brightest of them all - did not follow this rule, and were seen to change their location relative to other stars over time. The ancient Greeks, who believed that the earth was the centre of the universe and everything revolved around it, called them "wandering stars" or simply "wanderers" - planetai.

The five observable planets were associated with Greek deities, namely Hermes, Aphrodite, Ares, Zeus and Cronus. The Roman equivalents of these deities - Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn - are still their name in much of the world.

In various cultures, astrologers ascribed meaning to these planets, often that they represented the will of the gods, and in the Greeks' case, naturally, they represented that of their namesake.

While suggestions that the Earth is just another planet orbiting the sun date back to antiquity, it took the invention of the telescope in the early 17th century to improve people's understanding of the planets, and also led to the discovery of new ones. Uranus - visible to the naked eye in ideal night skies, but never previously found to be a planet - was discovered in 1781. Neptune was discovered in 1846.

These discoveries may have led to astronomy and astrology diverging, but while interest in astrology waned, astrologers nevertheless took new discoveries on board. Various interpretations of the "new" planets' significance were made, largely reflecting the period in which they were discovered.

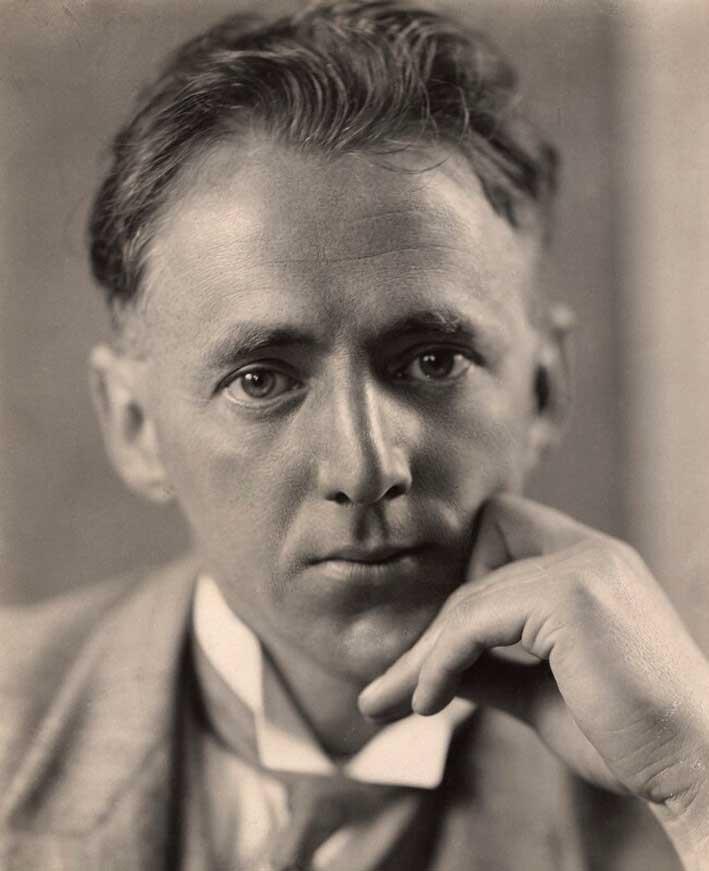

At the 20th century approached, however, astrology underwent a revival, not least through the help of Alan Leo, dubbed the father of modern astrology. Leo incorporated various traditions and beliefs, particularly from the east, and his 1912 book The Art of Synthesis is widely believed to have influenced Holst's work.

Astrology once more became a popular subject amongst artists and intellectuals, and it is through these circles that Holst developed his own interest.

A fateful holiday

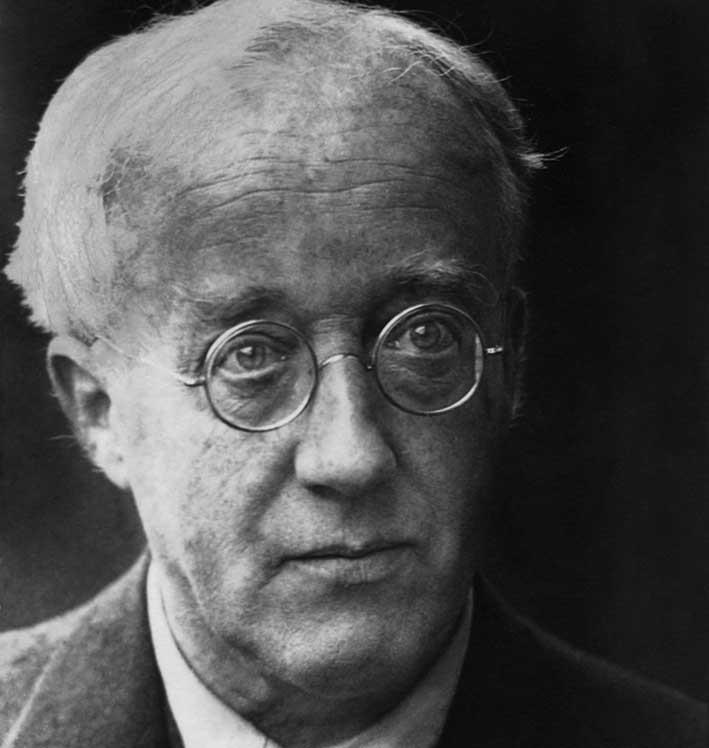

In the years preceding The Planets, Gustav von Holst - he only dropped the Germanic "von" prefix in World War I - often found himself disappointed with the lukewarm reception that his compositions often received.

In 1913, the main source of this disappointment was a mixed reception to The Cloud Messenger, his musical setting of an ancient Sanskrit poem. So when that spring, he accepted an invitation to travel to Majorca with a small group of English artists, Holst was in serious need of cheering up.

The island seems to have done the trick, but one of his fellow travellers, the writer Clifford Bax, unwittingly paved the way for Holst's masterpiece. Bax's own fascination with astrology rubbed off on Holst, and the two spent much of their holiday discussing the subject at length.

Bax also suggested that Holst should write a suite based on the astrological planets, and in 1914, he began by composing the first movement, Mars, the Bringer of War, completing the first sketch, appropriately enough, just as the first World War was breaking out. Venus and Jupiter followed that year, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune in 1915, whereas Mercury - the third movement - had to wait until 1916.

However, the work was only premiered - in front of a small, select audience - in 1918. Public performances of some of the movements followed, but the work was only performed in public in its entirety on 15 November, 1920.

Holst's "planets" are very distinct in character, reflecting their astrological significance. Mars, the Bringer of War, is appropriately warlike, while Venus, the Bringer of Peace is serene. Mercury, the Winged Messenger, is the quickest and briefest movement, while Jupiter, the Bringer of Jollity, is exuberant.

Saturn, the Bringer of Old Age, creates a sense of despair, but ends with a note of acceptance and reconciliation. Uranus, the Magician is suitably eccentric, while Neptune, the Mystic is ethereal, an effect no doubt helped by a woman's chorus which subtly enters the scene and which slowly fades out into nothingness at the end. In fact, Neptune is generally considered to be the first piece of music to use a fade-out, a technique which subsequently became ubiquitous in pop music.

While the work was inarguably ground-breaking and unusual for its time - in fact, in one of the first public performances, the conductor opted to give only five of the seven movements out of his belief that public could only absorb so much radically new music at one go - it proved to be a roaring success with the public.

But however disappointed he may have been at the lukewarm reception of previous works, neither did he enjoy the fame the work brought him. Shy by nature, he preferred to be allowed to compose and teach music in peace. Additionally, he grew to resent the way the suite overshadowed his other works.

So when Pluto was discovered in 1930, Holst, unsurprisingly, showed no interest in creating a new movement. However, he remained fond of his favourite movement, Saturn.

The Malta Philharmonic Orchestra will be performing The Planets at the Mediterranean Conference Centre on November 15 - exactly 97 years after its first public performance - under the direction of Greek conductor Michalis Economou, as well as works by Shostakovich and by the conductor himself. Tickets may be acquired through showshappening.com