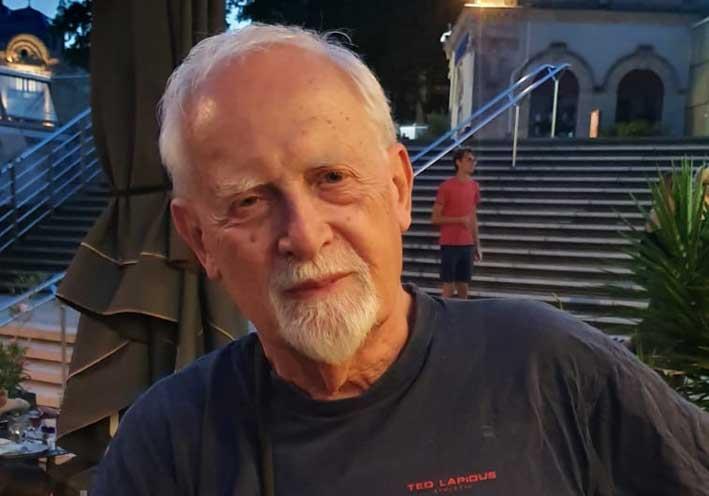

Patrice Sanguy was born in 1943. A retired Senior lecturer at Paris Dauphine University. He is the honorary president of the Franco-Maltese Society Cercle Vassalli which he had founded in December 1999.

"Here we are with my old friend Francis comfortably seated at the terrace of a bistrot, under the generous shade of pine trees. The scene is a square in the centre of the medieval town of Montpellier in southern France where I have retired after four decades of teaching in Paris.

We're enjoying lunch and chatting away the two hours ahead of us before Francis must check in the airport. By the end of the afternoon an Air Arabia flight will have taken him home to Nador, Morocco's main harbour on the Mediterranean coast.

Were it not for the face-masks donned by the waiters and some of the passers-by, this could look like any other month of August. Yet this month of August 2020 is unlike the others. And the conversation quickly drifts towards what has been the subject of the day worldwide for the past 7 or 6 months, namely the covid19 pandemic.

As far as I am concerned, I have no reassuring news to contribute. In the nearby village where I have a summer house, seven of the eleven staff manning the day care centre for babies under three have been tested positive. Our some 700 soul community can now boast the unenviable privilege of being the worst cluster in the department of Hérault. I have had to ask friends to cancel their visits. No doubt this is quite preoccupying after three months of lockdown and a couple of months of taking or not taking the precautions strongly recommended by those in charge of our health. This is the situation here in France but what about the other side of our common sea?

Today’s Diarist Patrice Sanguy writes from Montpellier

Father Francis is a French Jesuit priest who has lived most of his life in Morocco where he was born. He is well-known as a specialist of contemporary Moroccan literature and as a translator of modern Arabic into French.

But, as is customary for a Jesuit, he is immersed in the society where he lives and rather than discussing the current literary scene in Morocco, I am curious to know what life was like in Nador during and after the lockdown. I have had many accounts of the situation in other places in Morocco where I have lived myself a long time ago and regularly travel to but Nador is quite different from the rest of the kingdom.

Here a parenthesis for those unfamiliar with the large and multi-facetted country that Morocco is. Nador's main peculiarity is that it is located in the Northern region of Morocco, once under Spanish protectorate and next to Melilla a town which, like Ceuta on the strait of Gibraltar, has been in Spanish hands for almost six centuries.

In recent years, following the creation of the European Union and the Schengen space, Melilla has become one of the only two land borders of the EU on African soil. And as such, the Maltese will not be surprised to hear, like Ceuta, the town now attracts in their thousands migrants who flock to Nador in the hope of crossing into the European Promised Land.

This notwithstanding the presence of a 12 km long 6 meter high double fence all equipped with state of the art electronic devices. Funded by Brussels and erected in 1998, it runs along the border and is patrolled on both sides by Spanish and Moroccan police. Needless to say, trying to climb the fence is practically impossible and extremely dangerous.

As a result, the everyday lot of the migrants who camp in the forests on the Moroccan side is one of hunger, misery and destitution in spite of the help dispensed by charitable institutions like the Catholic one in which Father Francis is active.

The reader should not be misled into thinking that Melilla is, on a normal day, cut off from Nador and its African hinterland. For, contrary to the migrants, the residents of the sister towns are allowed to cross the fence in the daytime and they certainly do so in their thousands either to shop, thus fuelling the very active trade of the enclave, or to work.

Father Francis Gouin who was born and works in Morocco

Such was at least the case until, overnight in early March, the Moroccan government closed down all its borders with the outside world including with Ceuta and Melilla, in an attempt which at first proved relatively successful, to stop the pandemic.

This hit very badly those who depended on Melilla for their livelihood. Among them the many Moroccan women who used to enter the Spanish territory on foot and bring back heavy loads of cheap items to be sold in Nador's shops or market. And also the cleaning ladies working for Spanish employers who lost their jobs and, not being residents in Spain, were not eligible to furlough.

Foreign residents or tourists in Morocco were also affected though not to the extent of losing their daily bread. Many who were in Morocco for a short visit were trapped there and vice-versa. Francis told me the story of a Spanish Catholic nun who was unable to return to her community in Nador after a minor operation carried out in a Melilla clinic on the eve of the lockdown.

The Nador harbour itself was congested with European motorists (mostly retirees used to spending the winter months in tourist-friendly and affordable Morocco) queueing to go home to infected Europe. No easy task as only a few occasional ferries to the French harbour of Sète near Montpellier and chartered by the Paris government were sparingly allowed to sail in, one at a time and not on a regular basis, by the Moroccan authorities. Furthermore, those ships were not allowed to bring back any Morroccan nationals stranded in France.

Even now, despite the official end of lockdown, Morocco still fears the contagion coming from abroad. My friend shows me the printed out result of a Covid-free test he took two-days ago which he must show in order to board his plane.

Despite all those precautions, Morocco is, like so many other countries, experiencing a rebound or second wave of the epidemic, call it what you like. As many as 8 important towns across the kingdom including Casablanca, Tangier and Marrakesh have been cordoned off as of midnight on 27th July after a series of clusters were discovered beginning with 500 new cases detected at Safi on the Atlantic coast. Until further notice no one is allowed in or out of those cities under very strict penalties.

As I listen to Francis, many memories come back to me, and not just of my recent experience of lockdown, but of my childhood much of which was spent at the Moulay Youssef hospital in Rabat the capital of Morocco.

I belong to a family of doctors. A Maltese great-grand father on my mother's side, another great-grand father on the paternal side, plus my father and his elder brother who toiled for many years in Morocco in the days of the French Protectorate (1912-1956) and after.

All of them belonged to generations of doctors for whom the risk of epidemics was an everyday concern. And rightly so as, more often than not, the risk turned into reality, sometimes at their own expense or their family. Let me quote a few anecdotes to illustrate the point.

At the end of WW2, my uncle Charles Sanguy, then head of Casablanca's sanitary services, was confronted with an outbreak of the bubonic plague. He nipped the problem in the bud not because he had the drugs, which were even less available than today in those early post-war times, but thanks to some very drastic measures interestingly reminiscent of those currently implemented.

The resident general, then the highest authority of the Protectorate, gave him permission to have the economic capital of Morocco sealed off by the army. Only those carrying food supplies and other essentials were allowed into the city and this only after their clothes had been disinfected and they had had a shower. This to make sure they would not be bringing in the fleas which pass on the virus to humans. They were also given a free meal.

Our younger, or not so young readers, especially those who object to wearing face-masks etc., not to mention the many who think ill of vaccines when they exist and are outraged when they don't, may find the above shocking and infringing on individual liberties. Especially coming from a colonial power. No doubt they have a point here and a serious one especially if they are historians. But they must also remember that, just as there is no real treatment for the more acute cases of Covid19 today, antibiotics were not available worldwide until the second half of the 20th century. Like today hygiene and prevention were the medical professions' obsession, whether colonial or not. And this for very good reasons as once contaminated a patient's chances of avoiding death were almost nil. When they did even doctors were tempted to regard it as something of a miracle. Again let me give instances of this drawn from family lore.

Ten years before the Casablanca plague, my uncle Charles had been rushed with typhus to the hospital at Agadir upon returning from a vaccination campaign in the Sahara. Contrary to all expectations, he survived after having received the last sacraments.

In 1949 my baby sister Martine aged two also had typhus. Her survival was deemed so miraculous by her own father, yet a medical doctor like his brother, that the entire family went on a pilgrimage to Lourdes and that the little girl wore white and blue the Virgin's colours until her 16th birthday.

My memories go further back in time. As an old man born during WWII I grew up surrounded by people who had lived through WWI and had very vivid memories which they passed on to us.

One of my French great-grandfathers, a medical doctor trained in Montpellier who had saved other children from diphtheria was unable to save his own 4-year old little boy. The miracle did not take place the baby died. The father fell into a fatal depression. He took his own life and was denied a Christian funeral.

On the Maltese side of the family, they too remembered with a sigh no miracle could save my grand-mother's sister Annie although her father Enrico Magro, rector of the university was also a medical doctor. Like millions of others across the planet she fell victim to the second wave of the Spanish flu which hit Malta in the last months of 1919.

In those days the Maltese remembered with gratitude and respect the work of Temi Zammit who worked so hard to teach the Maltese farmer how to protect themselves and the rest of the island's population from the then rampant Malta fever and eradicate it.

Wash your hands, brush your nails, avoid contacts with people who cough or sneeze, make sure you eat or drink safe food, fruit and vegetables, only use clean dishes and cutlery, how many times a day were we repeated the same injunctions. Microbes and viruses are everywhere, epidemics can strike like thunder. Tuberculosis, malaria, cholera, polyomelitis, to name but a few were ever present and there was no way one could stress enough the necessity of protecting oneself.

Curiously, the lesson was lost after the discovery of antibiotics and generations grew up under the delusion that every single disease could be cured and that hygiene no longer needed to be as strictly observed as before.

Much of the disaster we have experienced this year, and are still experiencing as I write now, is in my opinion due to the now sadly ingrained idea that public health is the responsibility of those in power and the medical profession and nobody else's. Individuals are not to be expected to take their share of the burden and trouble themselves with the masks, social distancing etc. demanded by the prophets of doom and gloom and other killjoys.

Meanwhile, many of those who will not wear a face-mask, or clean their hands as they walk into a shop, will blame the epidemic on foreigners and are outraged if they themselves are treated like foreigners when they travel. Let's forget about the problem, they will tell you, I read on the Internet that a doctor somewhere had found a miracle cure, a vaccine is in the offing and will soon solve the problem altogether and it will soon be life as usual. We are no cowards and the best thing we can do is live as if the danger did not exist.

Sigmund Freud once said that we humans are torn between the conflicting principles of pleasure and reality. Accommodating illnesses is, whether we like it or not, part of reality. Living in denial of this hard fact will not lead us anywhere except to greater individual and collective disasters.

In 1909 a French doctor named Charles Nicolle, director of the Institut Pasteur's branch in Tunis, discovered that just as fleas could transmit the plague to humans, lice did the same with the typhus. He then spent the rest of his life pleading for hygiene and the right prophylactic measures. His work was acclaimed worldwide and he received the Nobel prize of medicine in 1928.

His remains are buried on the premises of the Institut Pasteur in Tunis where he is still revered as a national hero who fought illnesses on all sides and not just the typhus.

In 1933, three years before his death, Charles Nicolle wrote the following prophetic lines:

'There will therefore exist new diseases. That is a fact and it is inevitable. Just as inevitable is the fact that we will not be able to detect and trace them as soon as they appear. When we shall have a notion of those diseases they will already have reached so to say their final form and adulthood'. Destin des maladies infectieuses, 1933.

It is perhaps time to remember and meditate his words."*

To be continued next Sunday

Editorial Note:

Patrice’s mother, Denise, was born in Valletta in 1920 the daughter of a French naval officer who had married the daughter of the then rector of the Royal Malta University. She was related to the Caruana Galizia family.

*Patrice’s diary was too long to fit into one page but I was reluctant to cut it down as it is so very interesting so Part II will be published next Sunday.

[email protected]