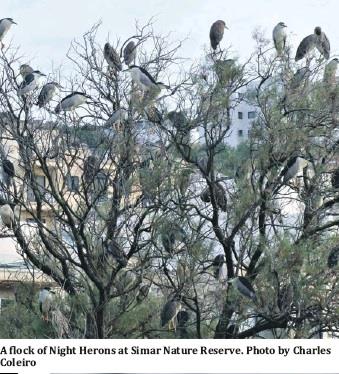

Thirty-two Night Herons lift out of the Tamarisk at Simar Nature Reserve. They’ve been contact-calling in the dense cover since early afternoon. Now, the conversation takes a businesslike turn as they clear the trees and marshal into a flock. Testing the evening air, they circle the reserve, and then the valley. They head south over the Wardija ridge but then appear to change their minds. Finally they gain height, spread out in V formation, and head southwest. A few minutes later I lose them somewhere in the setting red sky.

It’s a sight I see almost every day at this time of year. And yet, it never ceases to move me. I’m not alone. Bird migration has fascinated humans for thousands of years. The ability to cross seas, deserts and continents, and to do so as if guided by an invisible hand and a lust to survive, is pure poetry. Ecologically, it invites superlatives. The number and diversity of birds that fly between Europe and Africa have been described by Matt Merritt as an ‘extraordinary … enormous … twice-yearly transference of biomass from one hemisphere to another’. For his part, Robert Macfarlane writes of the ‘strong seasonal compulsions that draw creatures between regions, from one hemisphere to another’.

Every year as we roast on the beaches, something stirs in the north, hundreds if not thousands of miles away. ‘Zugunruhe’ is the German word for the migratory restlessness that many birds experience twice a year. Experiments have shown that caged wild birds will become more and more agitated as the seasons change. Exactly how they sense that the time is come, and how that sense takes flight over unmapped landscapes with millimetric accuracy, is not fully understood. Science doesn’t know everything, but it does know something. Birds respond to changing atmospheric pressure, length of day, the earth’s magnetic field, the map of the heavens at night and landscape features.

Whatever the exact recipe, we can rely on them to return. What we call the autumn migration is in fact a bundle of many kinds of journeys, depending on the type of bird, weather and place. It spans across at least four months, from August to November. Some birds migrate earlier than that: waders, for example, can head south from their breeding grounds in the far north from as early as the first days of July. The first Subalpine Warblers, too, can be heard calling in widien at around this time. Ducks, on the other hand, often reach us in late November and December, as do finches and plovers.

These migratory journeys can be long and complex, and broken up into lengths punctuated by stopovers. In Malta, this is something we’ve only just begun to properly understand. Until recently, any bird larger than a sparrow was lucky if it lasted more than a few minutes. Now, as the effects of 50 tireless years of bird conservation begin to be felt, birdwatchers are learning that the islands are not always just a place for birds to fly over.

Take the Great White Egret, a pure white bird with a wingspan that is not far short of two metres. This August, a migrating Great White Egret spent a few days in the company of a resident flock of Little Egrets at Simar and feeding around the coast in St Paul’s Bay. In its own time, it left its smaller cousins behind and moved on south, probably to North Africa.

Other autumn journeys are more direct and predictable. To many the highlight of the autumn migration, birds of prey appear in Malta between early September and early October. Honey-buzzards, Ospreys, falcons, kites, harriers and the occasional eagle follow established routes underwritten mostly by topography and wind direction. Seasoned birdwatchers will know where their best chances are, on any given day. The choicest spot is Buskett and the surrounding ridges. Every September afternoon for the past 40 years, groups from BirdLife Malta have hyperwatched this corner of the island. They’ve debated identification, taken stacks of photographs, and kept detailed notes. Ornithology aside, few sights are as memorable as a Honey-buzzard folding its wings and stooping from a great height into a pine that will be its roost for the night. For the oldest pines, every tree ring is a memory of a generation of tired, thankful birds.

The autumn migration, then, is about birds, but it is also about the landscapes they encounter. August and early September may be parched, but the intense heat only serves to heighten the smell of fennel, the sight of a sea of flowering squills, and the bright emerald dots of samphire. The first rains bring autumn narcissus and meadow saffron as surely as they do swallows, wheatears and wagtails. By the first days of October, the frosty-green countryside is alive with the song of Robins. Most move on to even warmer climates, but many carve out small territories and stay on for the winter. Bird ringing studies have shown that Robins can and often do fly thousands of miles to return to exactly the same place, year after year.

Here, I think, is where the word ‘instinct’ does us a disservice. Thom van Dooren has described how the penguins of Manly Beach persist in their loyalty to their nesting places, even as seaside bungalows mushroom in this busy suburb of Sydney. In Malta, this is the season that best summons similar thoughts about how memory works among migrating animals. Some of the birds we see in autumn are adults. They’ve made the journey before, possibly along routes that are exactly the same even as people transform them.

It is, however, juveniles that make up the bulk of migration: birds whose plumage tells of their first year of life. The message is complicated, but somehow they get it. If luck is on their side they will live on to fly back north in the spring and pass it on to a new generation. Partly the beauty of migration is that every cycle contains the promise of the next. The drab autumn redstart perched on a sea squill will return a splash of red and white and black on a giant fennel in April.

Circumstances have made this a time of staycations, immobility and relative isolation. It is also a time when nature steps in to rescue us. Like the Little Prince, we can still make our escape with a migrating flock of wild birds.

Note about the #onthemove campaign

This year BirdLife Malta has launched its #onthemove campaign to showcase the beauty of the autumn bird migration spectacle. The campaign aims to inspire people to enjoy, care and protect Malta’s birds during the autumn migration. Visit https://birdlifemalta.org/onthemove to learn more about the campaign. Members of the public are also being encouraged to log their bird sightings in a form which has been purposely created for this campaign: https://bit.ly/reportasighting.