It was fifteen minutes past one when Ibrahim Ali Al Shawesh, a Libyan businessman, turned onto the Sliema front on what was a quiet, sunny October afternoon.

Shopping bags in hand, Al Shawesh made his way to the well-known Diplomat Hotel, where he was staying.

It was then that the idyllic mid-afternoon peace was shattered.

A man in a bandana walked up to Al Shawesh, shot him five times in the head, sprinted around the corner and hopped onto a motorcycle which an accomplice blustered into life and rode off on.

Al Shawesh, probably dead before he hit the ground, was left lying in a pool of his own blood on the Sliema pavement, practically at the doorstep of the hotel he was staying at.

On that day, Thursday 26 October 1995, few could have foreseen the international ramifications that the cold and calculated assassination would have.

It took local police three days before it became apparent that Ibrahim Ali Al Shawesh did not actually exist.

Indeed, the man who had been killed in such precision fashion was Dr. Fathi Shaqaqi – a Palestinian doctor, known better as the leader of the Islamic Jihad, a group which had orchestrated a number of terror attacks on Israeli targets.

Today, 25 years on, The Malta Independent on Sunday looks back on an assassination which was a key moment in the continued tensions between Israel and Palestinians, and which put a target on Malta’s back.

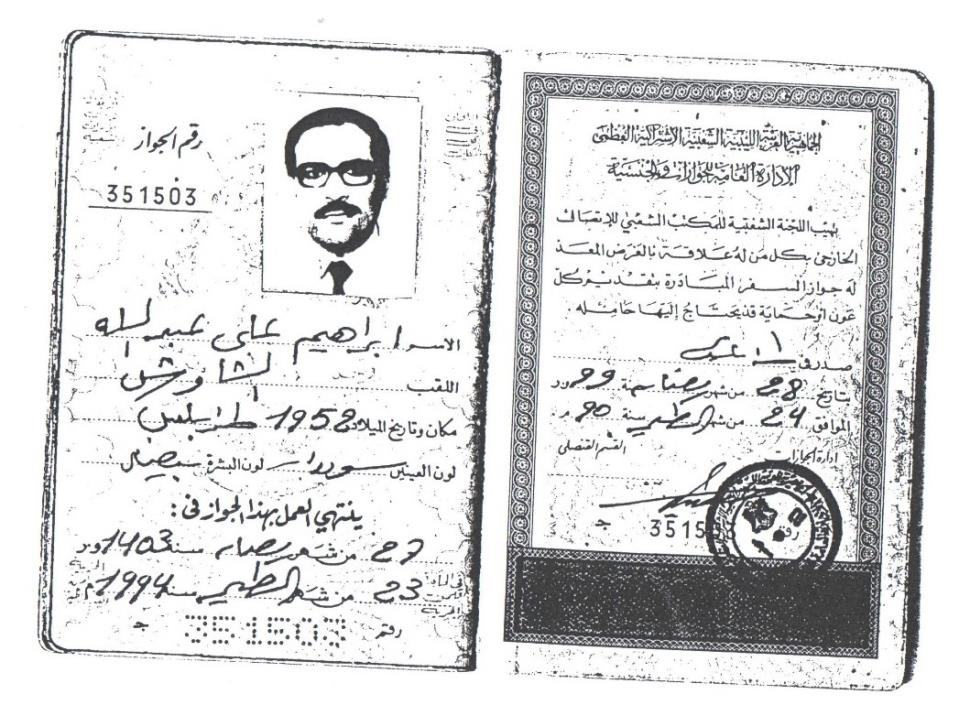

Fathi Shaqaqi pictured above on his fake Libyan passport, where he used the alias Ibrahim Ali Al Shawesh. Photo: Joe Mifsud Archives

Fathi Shaqaqi: from doctor to Islamic Jihad leader

Fathi Shaqaqi was born on 4 January 1951, in the slums of a refugee camp on the Gaza strip in Palestine. Getting his education through the United Nations school and through Bir Zeit University in the West Bank, Shaqaqi initially graduated as a maths teacher, but in 1974 he moved to Egypt to study medicine.

It was in Egypt that Shaqaqi’s political beliefs began to form. He felt that the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO)’s opposition to Israeli occupation of Palestine was worthless as it was not based on Islam; in fact, by the late 1970s he had broken away from both the Muslim Brotherhood and secular Palestinian nationalist groups, dismayed that the former spoke too little about Palestine and the latter too little on Islam.

In 1981 he founded the Islamic Jihad Movement in Palestine. The aim was simply to establish a sovereign, Islamic Palestinian state within the border of pre-1948 Palestine, except that the belief was firmly that these goals can be achieved through military means as per the Jihad – which translates to “struggle”.

Shaqaqi would be arrested twice by Israel, and the second time he was deported to serve his sentence in South Lebanon. Upon his release, he settled in Damascus, Syria, under the protection of the country’s President Hafez al-Assad.

It would be from here that Shaqaqi would lead the Islamic Jihad Movement.

A still of Fathi Shaqaqi addressing a Palestinian Islamic Jihad Movement Rally. Photo: Al Jazeera

Setting the scene

The scenario in Palestine since the state of Israel was declared by David Ben-Gurion in 1948 has always been delicate to say the least.

Decades characterised by warfare and killings would follow.

However, come the early 90s, a shift seemed to begin. Yitzhak Rabin became Prime Minister of Israel after calling for compromise with the country’s neighbours, and in fact the following year, Shimon Peres on behalf of Israel, and Mahmoud Abbas for the PLO, signed the Oslo Accords, which gave the Palestinian National Authority the right to govern parts of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. The PLO also recognised Israel's right to exist and pledged an end to terrorism.

Not everyone greeted the Oslo Accords with satisfaction though. Indeed, Shaqaqi was a key player in the setting of a coalition between liberation organisations, the Islamic Jihad, and Hamas against the Accords.

The Islamic Jihad continued on its warpath.

It’s first suicide bombings happened in January 1995, at the Beit Lid junction. Two Islamic Jihad members walked into a crowd of soldiers who were going through the junction to return to their posts after the weekend.

In a calculated and orchestrated attack, the first bomb was detonated within the crown, while the second one was detonated minutes later as people began to congregate on site. 20 Israeli soldiers and a civilian were killed in the attack.

Islamic Jihad claimed full responsibility for the attack.

The aftermath of the Beit Lid suicide bombing in January 1995.

In an Al-Jazeera documentary aired in 2018, titled Fathi Shaqaqi: Don’t Kill Him in Damascus, Israeli journalist Ronen Bergman speaks of how Prime Minister Rabin returned from Beit Lid to Tel Aviv “red with anger”, and details how he called in the chief of Mossad – Israel’s secret service – and ordered for Shaqaqi to be killed immediately.

The challenge for Mossad now was how to carry out the kill order while Shaqaqi lived in Syria and the country’s protection. It was eventually concluded that Shaqaqi could not be killed in Damascus, owing to logistical and also political concerns, because secret negotiations were going on between the two countries at the time.

An alternative was needed.

When Libyan strongman Muammer Gaddafi decided in September 1995 that, because of the signing of the Oslo Accords, the estimated 30,000 Palestinians in Libya would be expelled, Shaqaqi was one of a Palestinian delegation of three to visit Tripoli for talks.

This was Mossad’s chance.

The Malta connection

At the time there was an international embargo on flights in and out of Libya, which meant that Shaqaqi had to fly into another country to get to Libya through other means.

That other country was Malta. From Malta he would then board the Malta to Libya ferry, and arrive in the north African country through that means.

Mossad were aware of his movements, possibly through an informant who had embedded himself in Shaqaqi’s inner circle, and were waiting for him in Malta.

Shaqaqi travelled through Malta on 4 October, but it would not be until his return trip, three weeks later, that the move was made.

Talal Naji from the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, who accompanied Shaqaqi in Libya, told Al Jazeera in their documentary of how he had told Shaqaqi that he could arrange his return trip through Tunisia or Egypt because Malta was dangerous for him.

Shaqaqi however insisted that he would make his return to Syria through Malta.

The assassination and the escape

He arrived in Malta on 26 October 1995 under the alias Ibrahim Ali Al Shawesh. He planned to fly to Damascus the next day, and checked into the Diplomat Hotel that morning.

Witness testimonies detailed in Magistrate Joe Mifsud’s book Terror’s Footprints: Shadows of International Terrorism state how two men had been loitering around the hotel for the whole morning.

A foreign couple testified to police that just after one o’ clock in the afternoon, one of the two men walked up to Shaqaqi while carrying a black and blue bag when suddenly shots were heard. The couple did not see the weapon, which seems to have been concealed in the bag. Shaqaqi fell: the killer fired more shots into his body, before escaping round the corner into Arturo Mercieca Street, where his accomplice was waiting for him on a motorcycle.

Fathi Shaqaqi as he was found, face down on the Sliema pavement in front of the Diplomat Hotel. Photo: Joe Mifsud Archives

The motorcycle sped off, and was later found covered under the bridge in Manuel Dimech Street, not far off from the scene, which is where the duo most probably met a third person, who aided their escape via a car.

The motorcycle itself had been imported from abroad. The Yamaha XT-600E was in fact first exported from Japan to Spain, from where it ended up in Greece. There it was purchased by a man by the name of Harmand Philippe Rene. It was given Greek plates, and was ridden into Malta by Rene himself in August.

The motorcycle itself was found with a Maltese plate – Q-6904 – which it transpired had been stolen from a Yamaha 86 in 1989 – six years prior. This is a piece of the puzzle which is yet to be solved, but it may perhaps indicate some sort of local element to the assassination.

The fact that a forensic analysis of the motorcycle’s fuel found that it was fuelled up with a type of unleaded petrol that wasn’t sold in Malta at the time indicates that the motorcycle was not used until the day of the assassination.

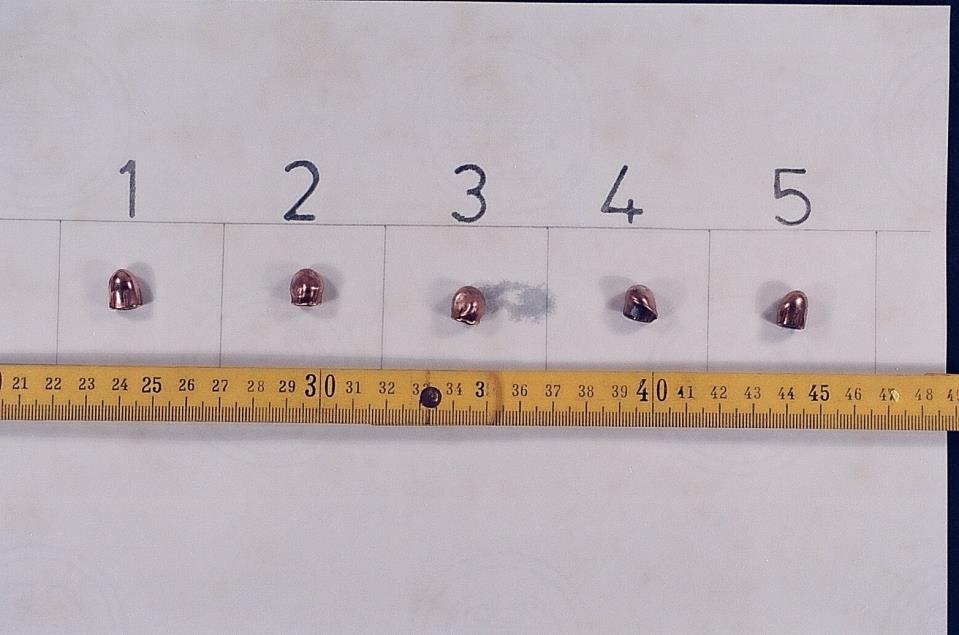

The short-range 9mm bullets used to kill Shaqaqi. He was shot five times in the head. Photo: Joe Mifsud Archives

There is speculation as to how the killers made their final escape from Malta, but the most likely scenario is that they escaped the island onboard a rubber dinghy (a RHIB) from Msida marina and onto a ship waiting at sea.

Indeed, Magistrate Mifsud’s book quotes workers at the Msida marina who reported seeing two suspicious people – who were at times joined by a third – loitering around the marina for some three days, to the point that the workers thought that the duo were sizing up a robbery.

The same witnesses told Mifsud that on the day of the assassination, maybe an hour after it took place, they had seen the trio close to Pier N of the marina. When they went somewhere else for a few minutes and returned, they were nowhere to be seen.

It was only when police released an identikit of the two alleged assassins that the workers realised whom they had seen at the marina.

Gordon Thomas’ book Gideon’s Spies theorises that the assassins left Malta towards a ship which had reported mechanical difficulties just outside Malta after leaving Haifa, onboard which was Mossad chief Shabtai Shavit. The ship, identified by Mifsud in his book as possibly being the Emily Borchard, in fact that afternoon reported to Italian marine traffic that its mechanical issues had been solved and that it would be returning to Haifa.

There have been other theories on how the killers escaped, not least one that they escaped on an aircraft to Djerba in Tunisia – with two flights leaving Malta to there on the day of the assassination. Speculation in this regard was reinforced when a Piper Lance with the registration 9H-ABU mysteriously crashed at sea on its way to Tunisia just five weeks later.

No evidence however has come to light supporting this theory.

Shaqaqi's watch amidst his blood-soaked clothes. Photo: Joe Mifsud Archives

The ramifications

It was not immediately clear that the man killed was in fact Shaqaqi. The front page of The Malta Independent on Sunday on 29 October 1995 in fact states that the police still thought that the victim was Libyan businessman Al Shawesh.

However, by then, reports were emerging that Shaqaqi had in fact been the victim: Reuters quoted two unnamed sources who identified Shaqaqi as the man assassinated.

The news was met with grief and anger in Palestine. The Islamic Jihad immediately pinned the assassination on Israel and warned that the assassination made every Zionist a target for them.

The assassination of Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhik Rabin – who had supposedly ordered Shaqaqi’s assassination – by a Zionist extremist, only six days later, was seen by the Jihad as “the blessing of martyr Fathi Shaqaqi’s blood.”

In Malta meanwhile, a crowd of demonstrators gathered at the Libyan embassy the Monday after the assassination, demanding that Malta arrest the perpetrators or face worsening relations with Arab countries.

It later emerged that the threat to Malta was far more serious than that.

In Terror’s Footprints: Shadows of International Terrorism Magistrate Mifsud details how he met Shaqaqi’s successor, Ramadan Shallah, for an interview in Syria in 1999.

Here, Shallah admitted that it had been agreed that attacks against Malta’s foreign interests would be carried out as a means of retribution for the fact that Shaqaqi had been assassinated on Maltese soil.

These attacks never transpired, but only because Shallah had insisted that their attacks should only take place within Palestine – a principle that the Islamic Jihad movement still follows today.

In terms of the case itself, Maltese police have not officially solved the case, but it is widely agreed that Israel’s Mossad was in fact behind the assassination.

The Islamic Jihad Movement – while weakened by Shaqaqi’s assassination – continued to operate and continued to carry out a number of terror attacks on Israeli targets.

Shallah remained leader until 2018, when he began to suffer from ill health. He died in June this year.

The Islamic Jihad Movement meanwhile is designated as a terrorist organisation by the USA, European Union, Australia, Israel, Japan, the United Kingdom, and New Zealand but continues to receive significant support from Iran.

Fathi Shaqaqi’s death continues to be commemorated in Palestine every year.