This two-part feature in the form of a study-paper examines the various measures taken by the authorities of the day to control the spread of disease, how it spread and the day-to-day reporting of cases. In many ways, it is noted that the reporting of cases and preventive measures have much in common with the present-day Covid-19 pandemic.

The 19th century is a period known for the outbreak of the plague and Cholera pandemics. The plague of 1813 had broken out in Costantinople and extended its ravages over the Mediterranean basis. The death of the daughter of a shoemaker, living in Sda. St Ursola (now, St Ursola Street), Valletta was the first case registered with a rapid rise in mortality leaving over 4,000 dead in its wake.

The first Cholera pandemic was registered during the period 1817-24. The disease brought devastation in all of Europe, including Malta when it reached the Island in June 1837 up till 11 October of the same year.

At one stage, it was reported locally, that when Cholera raged at Gibraltar in 1834 not a single medical man (though the majority of that class was greatly exhausted in the zealous charge of the most laborious duties) fell a victim to the disease nor were the clergy men of any persuasion attacked. At the time the debate was whether and how the disease was contagious as it was argued that only the old, poor and destitute could contract the disease.

The Governor Sir Henry Fredrick Bouverie (Courtesy of the National Archives)

Malta was under the Governorship of Sir Henry Fredrick Bouverie (1836-1843), a veteran of the Napoleonic wars. He was described as a refined, amiable man by his royal guest George, Duke of Cambridge. Known also for his qualities as a man of action who knew what he wanted and how to get it. He saw things very clearly and, having arrived at a deision, took up a line of action leading right to the goal. These qualities were a Godsend as the following year, after his appointment in 1836, his leadership was required to admister the Island in the face of the Cholera that visited Malta and Gozo.

A French caricature of Cholera Morbus from 1830

Appearance of first Cholera case

By means of a Minute dated 19 June 1837, the Governor of Malta, Sir Bouverie announced for the information of the public that the malady bearing every symptom of Cholera had made its appearance in the ospizio or asylum for the aged and indigent at Floriana on 9 June 1837 and continued to attack the persons, who were the inmates of that establishment, notwithstanding their removal to Fort Ricasoli.

The Governor attached a return of the cases of Cholera from its first appearance up to the date of his Minute.

With the exception of six of the individuals (three of whom were soldiers) included in his return, and three of whom were dead, the disease had been almost exclusively confined to the aged and infirm persons.

The Governor asked that official returns of cases of the disease were to be transmitted from every part of the Island to the Police physician and were to be then referred by the Governor to a Committee who would be able to frame their reports thereupon and transmit the same to government with any other information they may have.

Appointment of committee

The Central Committee for the supervision of cases of Cholera was composed of the following persons:

- Count Baldassare Sant - president

- Baron Vincenzo Azopardi

- Giuseppe Gauci Azopardi

- Dr Clarke - assistant inspector of Hospitals

- Dr Luigi Gravagna - Police physician

- Dr Liddell - physician to the Naval Hospital

- Nicholas Nugent - treasurer to government

- George Ward - secretary

Initial spread of Cholera

Since the commencement of the disease on 9 June up to 19 June, a Minute by the Governor of 19 June revealed 298 new cases recorded with a total of 200 dead and eight recoveries.

The secretary continued to provide daily updates with cases initially being reported from the following areas for the week ending 20 June 1837:

- Ospizio

- Ricasoli

- Valletta

- Senglea

- Lazzaretto

- Quarantine Port

- three cases on a ship which arrived from Palermo

- Fort Manoel

- Military Hospital

Gradually, as reports arrived on a daily basis, the Cholera was seen to infect more towns and villages.

For instance the daily report of 28 June 1837 showed new cases from Birkirkara, Floriana, Vittoriosa and Cospicua. The gravity of the siutation prompted the setting up of hospitals in Valletta and Senglea to cater for cases from these areas. Also dispensaries were opened at night in Valletta; the owners of which were Dr Fenech and Dr Duclos in Republic Street (then, Strada Reale).

The following day's report revealed that two new cases emerged from naval bakeries and one new case on board the H.M.S Hermes. Moreover, the spread of the disease had by now reached Ħal-Lija and Ħal-Ghaxaq. Fourteen new cases were also reported at the mental asylum. The situation necessitated the opening of more dispensaries, which were also opened by night in Valletta, Floriana, Cospicua, Senglea and Vittoriosa.

By 5 July 1837, Cholera had reached other towns and villages - Ħaż-Żebbug, Qormi, Sliema Rabat, Tarxien, Siġġiewi and Gudja were the next victims. On 6 July, new cases were also reported in Ħal-Luqa, Żurrieq, Ħal-Safi, Naxxar, St Julian's and Sliema, while the next day new cases emerged from Ħat-Attard. Mqabba became the next village to report its first case on 9 July.

By 14 July, the balance for cases carried forward from previous reports was standing at 981 cases with 346 new cases, 125 deaths, 84 recoveries and a total balance of active cases of 1,118 cases.

On 16 July a new case was reported in Ħal-Chircop village.

Gozo

On 17 July, Gozo's Cholera incidence position was as follows:

Active Cases from last report 24

New Cases 16

Deaths 7

Recovered 2

Total remaining active cases 31

A call for help

On 20 June 1837 a Government Notice was published whereby, on the recommendation of the Central Committee for the supervision of cases of Cholera, the Governor invited all medical men "who may be desirous of affording their professional assistance under existing circumstances to communicate without loss of time their names and residence to the Committee".

Remuneration was offered on pecuniary terms by government for all such assistance. The Governor ended his notice by saying that he was persuaded that this call would find a good response in mitigating "the unavoidable evils of the impending disease".

An expression of displeasure

Surprisingly, the following day, by means of a Minute dated 21 June, the Governor stated that he had learned, with no less surprise than regret, that several individuals, and among them some few Maltese medical practitioners had industriously circulated their opinions that the partial epidemic, which had visited the Island, is of a decidedly contagious nature. The Governor reiterated that a more cruel and unfounded doctrine cannot be promulgated; a doctrine opposed to the solemn decision of the eminent medical men collectively and individually, in the civilized world.

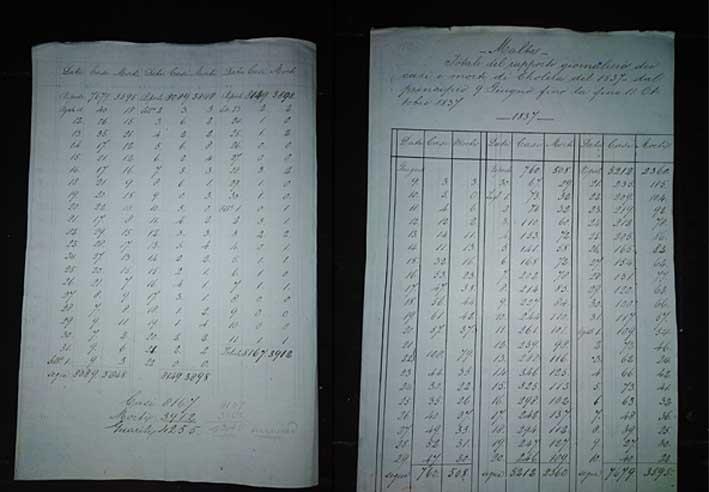

Return showing daily cases and deaths from Cholera of 1837 from 9 June up to 11 October 1837 with a grand total of 8,167 cases and 3,912 deaths and 4,255 recoveries

He also expressed his astonishment that these unpractised persons should presume to set up their unauthorised opinions, on an occasion of such vital importance, in opposition to such high and unquestionable authority. He ended his note by stating that: "The persistence therefore in such conduct on the part of those in employment of government, will immediately draw upon them the highest displeasure of His Excellency and will operate as a disqualification for those who may hereafter become candidates for public situations."

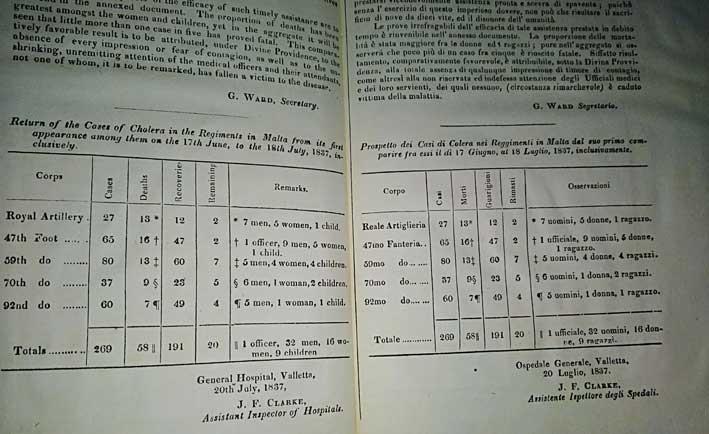

Cholera cases in the Regiminets of Malta

A total of 269 cases with 58 deaths and 191 recoveries were reported between 17 June up to 18 July 1837 in Regiments of Malta. Twenty cases were still active on 18 July. A total of nine children were also infected and are included in these figures.

Return showing cases of Cholera among the Regiments of Malta (cases attended to in Military Hospitals from appearance of first case on 17 June up to 18 July, inclusive

Cholera is speedily converted from a traceable and curable disease to a fatal one. Interestingly, one of the measures to contain Cholera in 1837, which the local Central Committee for the Supervision of Cases of Cholera suggested, was that practitioners of each town and village would implement 'the most rigorous and anxious enquires to discover those who may be threatened with some premonition of Cholera and not wait to be sent for'.

This is the second of a two-part feature in the form of a study-paper that examines the various measures taken by the authorities of the day to control the spread of disease, how it spread and the day-to-day reporting of cases.

In many ways, it is noted that the reporting of cases and preventive measures have much in common with the present-day Covid-19 pandemic.

Publication of report

On 20 June 1837, the Governor published for general information a report which was drawn up by the Central Committee for the Supervision of Cases of Cholera. Among other matters, he declared his intention to adopt the measures of the report in the hope of arresting the progress of the disease which had partially manifested itself on this Island.

A number of field hospitals were opened in towns and villages such as the Mqabba Field Hospital

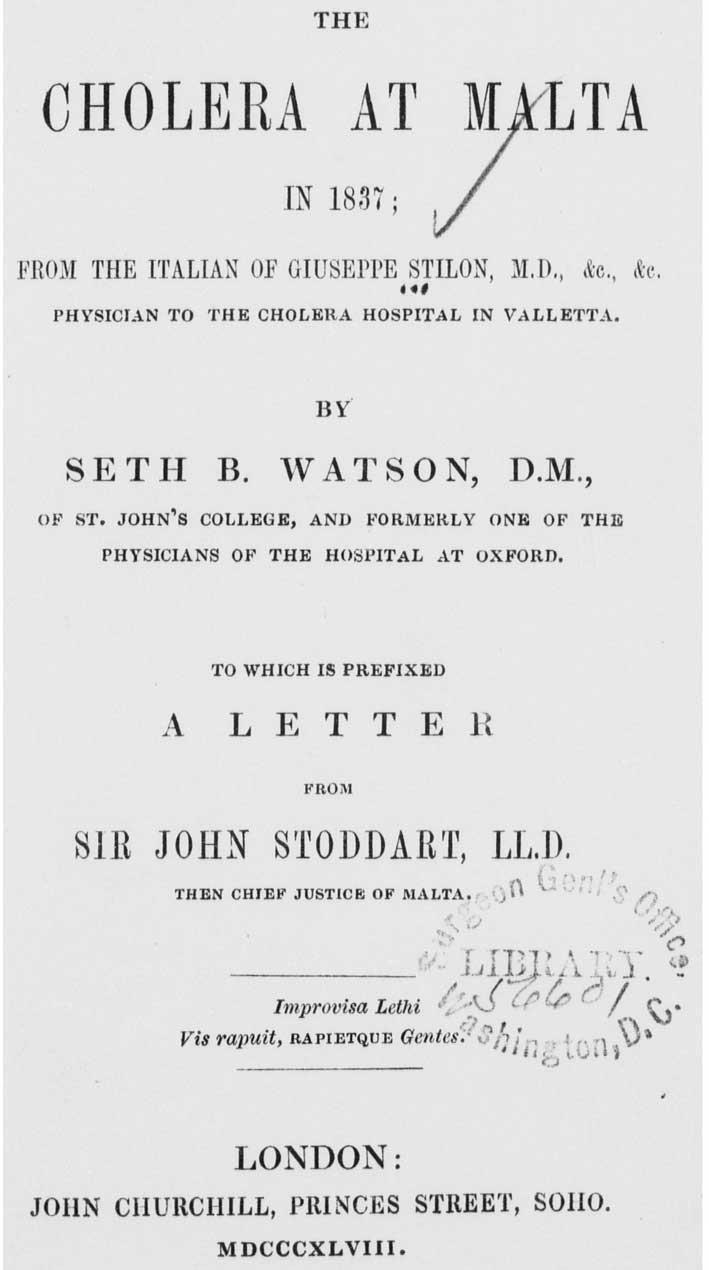

The frontispiece of the book, titled 'The Cholera at Malta in 1837 from the Italian of Giuseppe Stillon MD Physician to the Cholera Hospital in Valletta' by Seth. B Watson

The following is a summary of the report's suggestions:

1. The setting up of a large and well arranged hospital for each of the country's districts situated in the highest and most airy part of the Casal furnished with very requisite comfort.

2. The formation of a local committee in each Casal consisting of the deputy Luogotenente, parish priest, principal medical practitioner and respectable inhabitants.

3. Each committee was to remove any accumulation of filth in the streets, courts and cellars; to visit such houses situated in narrow lanes, low and damp places and to see that proper cleanliness is observed, and that houses are ventilated.

4. To seek to discover any cases of concealment of disease and encourage heads of families to apply for immediate medical assistance, but no compulsory measures were to be taken to remove them to hospital.

5. Literature on the disease was to be disseminated through parish priests.

6. Medicines were to be provided at the expense of the District Hospitals as well as in every Casal.

7. During the hot season individuals were warned to shun crowded places.

The report reached its conclusions on the lines that the dread of infection would not deter relations and friends from bestowing that care and devoted attention to the sick which was of such vital importance in the disease. It was also indicated that experience from all countries had shown that where the disease had prevailed those who attended upon the sick were not more liable to attacks of the disease than those who had no communication with them, but that those who are predisposed to the disease would receive it without the least contact with the infected person.

Contagiousness of Cholera

Due to the debate on the level of contagiousness of Cholera at the time, the Central Committee for Supervising Cases of Cholera also published authoritative sources from leading physicians and hospitals of the time to tranquilize the public mind about the non-contagiousness of Cholera. Authoratative medical practitioners from Paris and opinions of equal weight and evidence from England were cited as follows:

- Physicians and surgeons of the Hotel Dieu declaration (31 March 1832)

- St Lews's Hospital (6/7 April 1832)

- Hospital of Notre-Dame-de-Pitie' (30 April 1832)

On 3 July 1837, The Central Committee for supervising Cases of Cholera published an extract from a highly interesting official manifesto (promulgated during the prevalance of Cholera by the Magistracy of Health sitting in Genoa) dated 27 July 1835 whereby it declared that "a good diet, courage and prompt medical assistance and confidence in the Divine Mercy are the real preservatives against the prevailing scourge, the others are but an error now dispelled".

Cholera hospital visits

On 4 July, the Maltese Members of the Medical Profession and Medical Students at large were invited to visit the Cholera Hospitals in Strada San Cristoforo in Valletta (now St Christopher Street) and at the convent of St Philip, Senglea and the Military Hospital in Strada Mercanti (now Merchants Street) to familiarise themselves with the prevailing disease and to be acquanited with the mode of treatment pracised there.

Proclamation

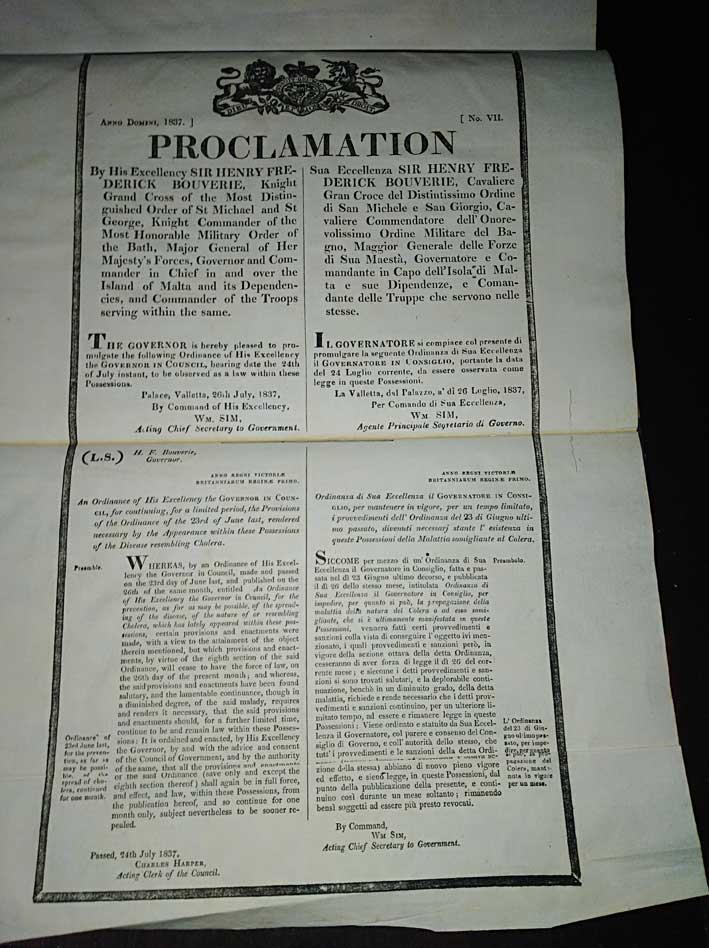

On 26 June 1837, the Governor issued a Proclamation whereby he promulgated an Ordinance of the Governor in Council dated 23 June to be observed as law. The powers invested the Governor and the Central Committee for the Supervision of Cases of Cholera as circumstances would permit and were the same as those granted in England.

Ordinance by the Governor in Council for continuing for a limited period, the Provisions of the Ordinance of the 23 June 1837 for the prevention as far as may be possible of the spread of Cholera continued for one month

Disappearence of the disease

On 24 August 1837, the Governor issued a notification to the Central Committee for the Supervision of cases of Cholera whereby he stated as follows:

"The disease, which has oppressed this Island having, by the blessing of God, become more moderate, and there appearing to be good reason to hope that it will soon altogether disappear, it is not my intention to propose to the Council of Government that the extraordinary powers with which your Committee, and myself have been invested, and which will expire on the 26th instant shall be renewed; nor do I consider it necessary that your Committeee shall remain embodied beyond that day.

In taking leave of your Committee, I request that you will do me the favour to accept my best thanks for the zealous manner in which the duties which have devolved upon you have been performed and for the assistance which you have rendered me, during a period of no ordinary anxiety."

Regulations by Dr Gillkrest

On 8 October 1834 the Malta Government Gazette published a copy of the regulations drawn up by Dr Gillkrest, a principal medical officer at Gibraltar. The Regulations sought to tranquilize the minds of people of all classes on the subject of cholera should the disease at any time break out again.

These regulations concerned the following points:

1. Dwellings

- Utmost cleanliness to be observed; apartments to be kept as dry as possible and properly ventilated

- More space for people living in a small single room

- The importance of light and sun in the room. Ventilation during the night.

- The avoidance of dampness

- The importance of keeping warm and hence chimneys running, exposure of bedding, sofas and so on to the air and sun

- Whitewashing only to be done in fine weather

- Keeping drains and cesspools clean and the use of chloride and lime to remove foul odours

2. Diet

- Avoidnace of late meals and eating light suppers

- Avoidance of raw vegetables, fruit, cold fish or cold potatoes

- Soups to be free from hard animal and vegetable substances

- The proper and not hurried mastication of food

- Cheese, sausages and other articles likely to become deteriorated by keeping should not be taken on an empty stomach

- The poorer classes were cautioned against cooking vegetables which have been too long kept or any other articles of food of bad quality which from their cheapness, those classes are sometimes tempted to buy

- Goat's flesh and flesh of young calves to be abstained from; bonitos, horse-makerel and shell-fish in general to be used sparingly and not at all at supper

3. Wines and spiriits

A moderate quanity of good spirits and water may with advantage be subsitutued for wine of doubtful quality.

4. Medicines and medical treatment

The public was cautioned against drenching themselves with medicine for it had frequently occurred that an ill-timed dose had, instead of warding off Cholera, brought on an attack.

It was pointed out that Cholera was preceded by diarrhaea or slight bowel complaint. If neglected the worst consequences had, too often followed. It was desired that the poorer classes, if ever so lightly affected with bowel compalints to get the help within their reach.

Social and political implications

The outbreak of Cholera is to be seen within the wider social and political context of the time and place where the outbreak took place. The disease caused social reactions such as in France in 1830 where the epidemic broke out in a period of political troubles. This contributed to reinforce both the political conflicts and the social representations. In Malta, the epidemic paved the way for a Maltese Anglophile upper class. This is revealed in a study made by Dr David Zammit.

Bibliography and References

The first part of this feature was publish last Sunday

To be continued