Not all career paths are conventional. But it’s generally the less conventional career paths which are the most fascinating.

That statement stands the test in the case of Jacqueline Grech Licari.

A Maltese University of Malta graduate, Grech Licari’s career sees her take in and work amongst one of the most incredible natural spectacles that the world can offer: volcanoes.

Speaking to The Malta Independent on Sunday from where she is currently based in Iceland, Grech Licari details her path to following her dream of becoming a volcanologist, and gives her insight into some of the characteristics surrounding volcanoes and how they can affect the area around them.

It’s a dream which started early on: Grech Licari explains that the aspects of physical geography – be it climate change or natural disasters – had always interested her, but that it was when she was 12 years old that a geography lessons based around volcanoes really prompted her fascination.

“I actually went up to my teacher and asked what I had to do to become a person who studies volcanoes, and she stared at me blankly and told me that it’s not really a thing in Malta,” she recalls with a smile.

However, a couple of years later the University of Malta opened the Bachelor of Sciences in Earth Systems course, presenting the opportunity for fieldwork – including to volcanic regions – abroad.

Grech Licari graduated with a First Class Honours and set about searching for the next step for her to follow her dream of following a career studying volcanoes. In the end, she settled on Iceland – a spectacular country known for being one of the Europe’s volcanic hotspots – where she enrolled into a Master of Science in Geology with a specialisation in physical volcanology and geochemistry.

She graduates this October, having just submitted her thesis, which focuses on volcanic activity on the Reykjanes Peninsula, which is the closest eruptive area to Iceland’s capital city Reykjavik.

“My research focused on one of the last eruptions to have happened there around 800 years ago – back in 1210. I took samples from it and I was studying the physical aspects of them to identify things such as lava flow and ash generation, before then studying parameters, such as the explosivity of the eruption and where ash was dispersed, which can then be used by volcanologists to model how another eruption would affect today’s infrastructure,” she explained.

Luck would have it, in a way, that the same volcanic area would erupt right as Grech Licari was writing her thesis, meaning that all she needed to do was compare the chemistry and dynamics between the eruptions and see how they differ.

Eruption sites, chemical samples, 3D modelling: what does a volcanologist do?

The job of a volcanologist involves several things. The most obvious pertains to when a volcano actually erupts.

“In the case of an eruption, we are the first to be deployed to the eruption site so that we can take different kinds of samples which are studied in the lab so that we can get an indication on how the eruption is behaving,” Grech Licari says.

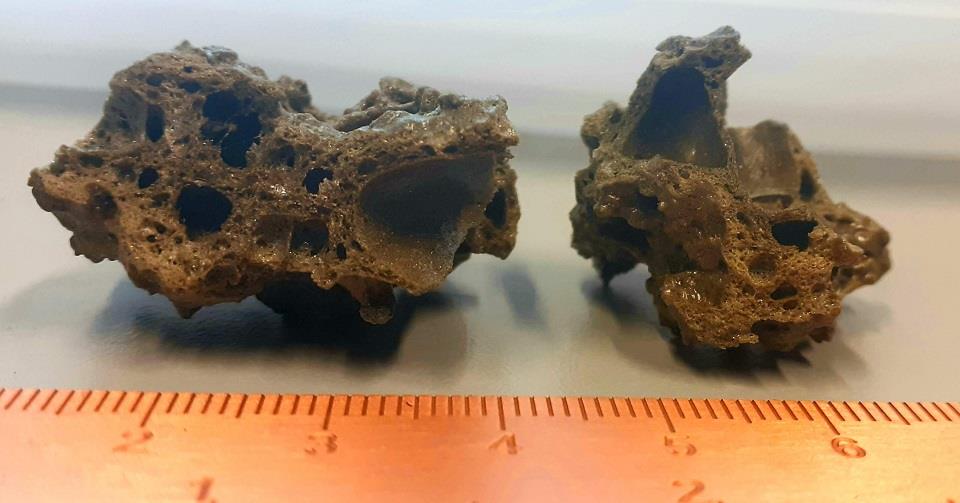

“We do the same thing with rocks which have just formed – lava which is still warm but which is solidified, and with tephra – which is essentially anything which is ejected from the volcano during the eruptive event,” she continues, explaining that tephra can be anything from ash or small-sized bombs called lapilli and that it can indicate the characteristics within the volcano.

Another task which volcanologists have at hand is to utilise drones in order to create 3-dimensional models which will allow them to identify how much volume there is in the volcano, lava would flow, and whether there are any risks based on the velocity of the flow.

Grech Licari explains that, through droning, the team she was with in Iceland spotted a very rare phenomenon during the eruptions on the Reykjanes peninsula.

“There were two eruptions – one in 2021 and one in 2022 – in the same area, with the lava flow of the second eruption flowing onto the same lava flow of the first eruption. What was very interesting is that as the new lava started to flow onto the old lava, the pressure pushed lava from the 2021 eruption which was still molten but not moving upwards, thereby creating a new flow from that 2021 eruption,” Grech Licari says.

“It was fantastic to observe, and it’s obviously very good to study these phenomena so that we can be more informed from a safety perspective,” she adds.

There is more to the job than just being on site for ongoing volcanic eruptions though. Grech Licari explains that when not studying ongoing eruptions, volcanologists study older eruptions in order to create models for what could happen in the case of future eruptions in the same place.

To do so, she explains, older lava is sampled, as are materials such as crystals, minerals, and volcanic glass – which is the type of rock created when what is fired out of a volcano is cooled very quickly. The chemical composition of these materials are analysed, as are the sizes and shapes of the particles because this can indicate whether the eruption was explosive or not.

Besides that, Grech Licari said that they also carry out a lot of modelling to see where the ash would go in certain weather conditions, to determine possible lava flows, and to identify what different behaviours there could be in an eruption.

Volcanoes and climate change: a surprising relationship

Climate change has – and will continue to have – a profound effect on our lives. But while climate change can be the cause of extreme weather and an increase in natural disasters, it doesn’t have a profound impact on volcanic patterns.

“It’s not extremely significant,” Grech Licari says when asked whether climate change has an effect on volcanic activity.

“There have been some effects observed across geological timeframes – not human timeframes – in certain areas which have a lot of snow or glaciers. When you have glaciers decreasing in size, the decrease in pressure on the land can cause an effect similar to that of an over-pressured bottle, in that when the pressure is released, the bottle overflows,” she says.

“The same thing happens in volcanoes: when you have magma stored beneath the surface and you release such a huge amount of pressure because of the decrease in mass in the glacier, then there is an adjustment period which results in increased eruptive activity,” she continues.

“Once it reaches a balance though, it will not cause more eruptions than it used to… the increased activity is just until the volcano figures the new balance out,” she adds.

More interesting, however, is how large explosive volcanic eruptions can cause changes in climate.

When a volcano is higher up, such as in Iceland, or lower down in latitude, then it is easier for these volcanoes to eject all their gasses into the stratosphere, being that the stratosphere is closer to the Earth’s surface at these latitudes.

The stratosphere is where one doesn’t have weather, Grech Licari explains, meaning that anything ejected into this part of the atmosphere remains there until it disintegrates. This is how a major volcanic eruption can affect climate.

“If there are a lot of aerosols or bits and pieces of cryptotephra, which are non-visible particles of volcanic ash, dispersed in this area they can take a few years to disperse and they will reflect the sun’s energy outwards before it reaches the surface which can actually result in global cooling,” Grech Licari says.

She points out that this is a phenomenon which only happens in the case of major eruptions. One such eruption was the 1783 Laki eruption in Iceland which erupted for months and was at such a scale that its output caused global cooling across the northern hemisphere.

This is a phenomenon which normally reverts however within a decade or so, she adds.

“So in terms of long term climate change, volcanoes are not responsible and it’s mostly human use which is the cause,” she concludes.

Malta and Mount Etna: What are the dangers?

One of the most obvious questions when it comes to Malta relates to Sicily’s Mount Etna, one of the most active volcanoes on the planet which has had particularly dramatic eruptions in the past. This volcanic activity is monitored, but can it be predicted?

“With every volcano, there are signs where you will know that something is brewing – for example there is magma coming to the surface – but you can’t really tell when it’s going to happen… you just know that something is going to happen,” Grech Licari says.

As part of her work in Iceland, for example, Grech Licari says that they knew that something was going to happen because their seismograms registered tremors and deformation of the ground as it starts to lift upwards because the magma was coming closer to the surface.

Based on the frequency of the earthquakes they can then sort of determine where the eruption will happen and they can then use models based on that which then give them indications of eruptions in different locations.

The same thing is done at Etna, Grech Licari says, by the INGV which is one of the leading expert groups in volcano monitoring.

All monitored volcanoes have an alert system, and when there is increased activity the alert system will switch from green to yellow, and then to orange or red if it is erupting.

So what are the dangers for Malta if there had to be a major eruption at Mount Etna?

“It depends,” Grech Licari begins.

There are several volcanoes which are quite close to Malta, not just Etna. Vesuvius, Vulcano and Stromboli, for instance, are both close.

“What’s good about Vulcano and Stromboli is that they erupt very frequently which means that, just like with the gas pressure in a bottle, if the pressure is being constantly released then it won’t overflow,” Grech Licari says.

In Vesuvius’ case, the volcano has been dormant for centuries; if it does erupt it will be an eruption with a significant amount of volume and a lot of ash. Etna is a bit if a unique case, though, she says, and eruptions can vary quite a bit.

The danger for Malta could be if Etna were to erupt like it did in 122BC, she explains. The 122BC eruption was one of the worst on record for Etna, and it was so violent that it caused significant damage to the city of Catania, had a huge ash column which went into the stratosphere, and caused the collapse of a flank of the volcano into the sea.

“A flank collapse into the sea would be the more pressing issue for Malta because of the risk of a tsunami,” she says.

In the case of the ash, the worst-case scenario would mean that flights would be cancelled and people would have to close their windows and stay inside until the ash dies down, but it wouldn’t be a long-term measure.

“The tsunami however is what one would need to be aware of because it can happen very quickly since Malta is so close to the volcano. If there were to be a flank collapse the north-east of Malta particularly would be very susceptible to a tsunami,” she says.

The key to the dream: never give up

Even from a half-hour interview, it is clear that Grech Licari is living out her dream. That dream will continue to develop as she has been selected to follow PhD in at the Victoria University of Wellington in New Zealand focusing on the eruptive history of the White Island volcanoes.

So, what advice can she give to anybody wishing to follow the same career path as she has?

“First and foremost: don’t give up,” she says, noting how because volcanology is such an unconventional career path there will be many people who have doubts about it.

She said that people should stick with some sciences but that there’s no need to know everything at once. Grech Licari says that while she followed Chemistry and Physics in Malta, she had no experience in geology – but this was solved by taking extra classes in Iceland as part of her Masters course.

The upshot is simple: “Never give up, keep pursuing sciences and speak to others in the field so that they can give you advice.”

Aspiring volcanologists can get in touch with Grech Licari on Twitter, where she has the Twitter handle of @GrechLicari.