You were President of the Labour Party in the mid-1980s. It was a tough time for Malta. The MLP had won more seats in Parliament without having obtained the majority of votes in the 1981 election. How would you describe those eventful, difficult years? Shouldn’t the Labour Party have conceded defeat?

The difficult years had started prior to 1981. With the change in the PN leadership in 1976/7 following the resignation of Dr George Borg Olivier and the arrival of Dr Eddie Fenech Adami at the helm. The PN changed strategy altogether and went on a straight confrontation with the ruling MLP while broadening its appeal towards slices of the electorate that previously were considered to be pro-Labour by definition. As the Labour government sought to introduce reforms like for pensions or how newly graduated doctors would spend two years working at the main hospital, then St Luke’s, the PN backed through and through the contestation that emerged.

Moreover, within the Labour leadership there grew the suspicion that the PN Opposition wanted to undermine the aim of completely phasing out the presence of the military base by 1979, which was the centrepiece of all that Labour had been doing since 1971. This ignited resentment to a much greater degree than was then imagined in right wing circles or elsewhere. It fuelled the mobilisation of street action by Labour heavies (and sundry fellow travellers/agents provocateurs) that spilt over into unacceptable violence (like on The Times and on Dr Fenech Adami’s residence in October 1979, but again, these were prompted by an attempt, rarely recalled, on Dom Mintoff’s life in Castille on the same day).

The elections of 1981 were won by Labour with a minority of the popular vote and a majority of seats in Parliament. That could easily have happened in the 1971 elections with the blatant gerrymandering of district boundaries by the Nationalist administration. The attempt was nullified by Labour’s unexpected net win of 5 votes in the Siggiewi district; had it gone differently, the PN would have proceeded to govern. That point was clear to many Labour leaders and supporters and they had kept it in mind.

Moreover, Labour’s 1981 win was totally in line with the Constitution as well as in line with what happened in other democracies, not least the British one, which our system was based on. In 1951, a similar outcome had prevailed in the UK, when the Conservative Party took over the government with more than a million votes less than Labour’s. In other systems like in the US, similar scenarios had developed (the latest in line being the Trump presidential victory of 2016). There was no constitutional rationale for the suggestion that the Labour party should have conceded defeat.

This having been said, it was clear that the situation was politically indigestible, also for many of Labour’s leaders and rank and file. PM Mintoff proposed that Labour should govern for two years and call anticipated elections (personally I believed this was the best approach, but at the time, I was outside the loop).

His proposal found little traction and the political process moved slowly and very painfully towards finding a wide ranging compromise that would, in future elections, deliver a majority of parliamentary seats to the party which in a two-sided race won the absolute majority of the popular vote. Most people on the Labour side were convinced that the PN would never have conceded this had they won in 1971. (Perhaps one should keep in mind as well that in those days majorities of the popular vote were secured by what now would be considered as derisory margins, in the ballpark of 4,000 votes.)

Eventually the compromise took the form of a trade off, “majority rule” coupled to a constitutional guarantee on the basis of an enshrined neutrality clause to ensure that the decision for Malta to cease operating as a military base would not be reversed in the future.

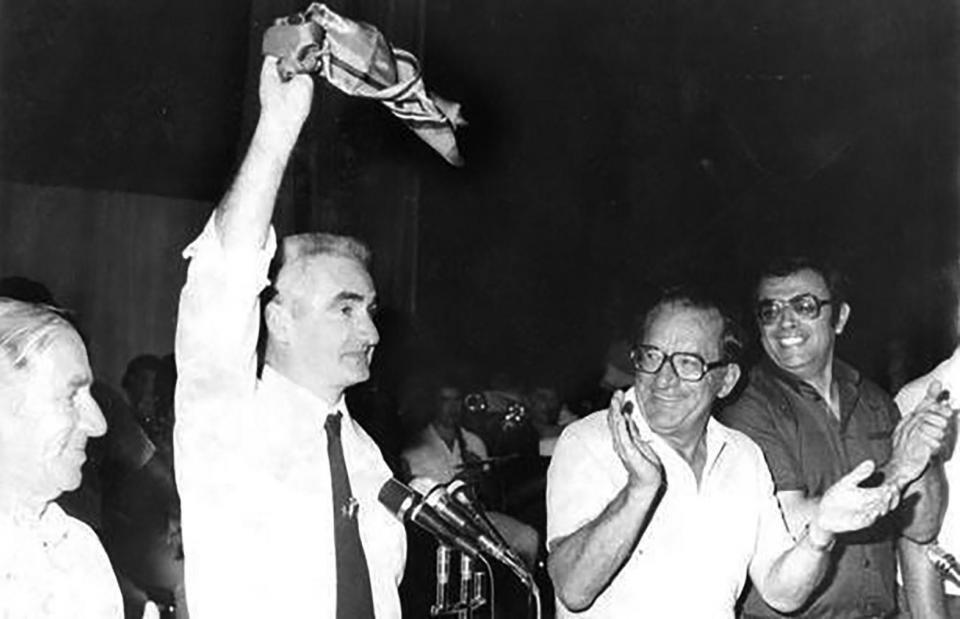

Alfred Sant (right) at the Malta Labour Party’s annual general conference in 1986 with then Prime Minister Karmenu Mifsud Bonnici and then MLP secretary general, Marie Louise Coleiro

It was a time of violence and civil unrest, with the PN initially boycotting Parliament and embarking on a campaign of civil disobedience. It culminated in the Tal-Barrani incidents and the murder of Raymond Caruana in 1986. Later years showed us that you worked hard to eradicate the violent elements within Labour. So how could you be comfortable as party president when so much violence was happening? Did you make internal pressure on the then leaders to calm the waters? How did they respond?

Your narrative implies that violent elements were to be found uniquely on the side of the Labour Party. Which is not correct. As of the late 1970s to 1987, there were numerous bomb attacks on residences and public edifices. The Deputy PM’s house, the residence of the PM’s brother, the house of the Police Commissioner and a police station (where a police officer was seriously wounded) were among the targets. Surely, these could not have been run by PL “violent elements”. The perpetrators were never discovered.

Curiously, the final strike in this sequence happened shortly after the PN won the 1987 general election and it happened on a tourist bus. Nobody has ever remarked on this bizarre ending but it still seems to me like somebody was placing a reminder about the clearance of “invoices” related to the bombing incidents that had been left pending. There were no further disturbances of that sort in later years.

Again your narrative overlooks the fact that the PN during some of these years at least built up a group of trained – there’s no other word for it – squadristi. Ostensibly established to defend the PN against Labour’s tough guys and street “hotheads”, their remit went much further though good care was taken to keep it under the radar. When some of their activities came out into the open following a police raid on the PN headquarters, the PN took their first serious hit in public opinion in the years subsequent to the 1981 election.

All this is not to excuse Labour’s frequent reliance on the strong arm deployment of scores of “militants” on the streets to make a point or shout down opponents of the Labour government’s approaches. I have discussed this problem at some length in my book of reminiscences published in 2021 “Confessions of a European Maltese – The Middle Years” and in a discussion of Dr Fenech Adami’s political record in “Fehmiet u Għarfien” published last month.

In fact, during the years 1979-1987, both political parties risked being undermined by a loose alliance of criminal actors, coming from both sides of the political fence, or indeed without any real political allegiance, who were probably acting in collusion with each other. These were driving the sporadic violence that became part of the political scenario.

My view in all this was that contrary to what the right wing press was all the time emphasizing, the huge majority of Labour supporters, workers, middle class employees, self employed, pensioners, wanted their party to win arguments and elections but were totally against violence in how it did this. Against the background of the tough language that both parties were deploying to put their claims forward, this needed to be asserted. Labour was not in a lager, just defending its claims against surrounding forces, but had an agenda for change that was based on clear objectives, that were being contested by people who disagreed with, or misunderstood them. Such objectives needed to be clarified and explained.

As President of the Party and before that as chair of a party Information Department, set up in early 1982, with colleagues of mine, we launched grass roots consultations and meetings within the party that made these points while pushing forward the Labour government’s message, tying it in as well to an overview of how socialism (including in its Marxist variants) had progressed in Europe. That approach made sense and had resonance (though few noticed this) because it was not driven by government ministries or by ministers, but by people working from within the party structures.

It was when leaders realised that “ordinary” people working within the party structures or supporting the party from “outside” resonated to this kind of discourse, that they started giving it attention. All this may sound anodyne to you, but it worked.

I mentioned Raymond Caruana. But I must also refer to the murder of Karen Grech in 1977. Two political murders that remain unsolved to this day. Over the years there were times when it was said that there was progress in investigations. But the culprits were never caught. What are your thoughts?

Personally I doubt whether the police force was equipped well enough, intellectually and technically, to handle both cases, which were politically highly charged and not so easy to investigate. This was compounded in a crucial way by the political interference to which the police corps was subjected, not just in terms of the government’s heavy handed controls within the administrative system, but just as much in terms of the Opposition’s networks of informants and worse within it.

Both cases hit as well the omertà factor that is very present in Maltese society, in Karen Grech’s case that of the professional castes, in Raymond Caruana’s that of the street militants/hoodlums. My conclusion right across was/remains that as part of the radical modernisation exercise that Malta needed to go through, modernisation of the police force on a number of levels has to be a top priority. Later, I did get the chance to try and get such a reform moving and I believe it would have worked but it was aborted as of the fall of 1998.

Karmenu Mifsud Bonnici (second from left) appointed Designate Leader of MLP on 15 October, 1982, in the presence of then Prime Minister Dom Mintoff Photo: Times of Malta

In the years when you were president of the party there was the transfer of power from Dom Mintoff to Karmenu Mifsud Bonnici as Labour leader and PM. Mifsud Bonnici was “imposed” by Mintoff. Nobody had dared dispute that choice, at least in public. Today, 40 years later, can you say if there had been any internal resistance to this move?

The choice you mention though had been brewing for five years at least.

Post-1979 and prior to the 1981 election, the belief was widespread within the MLP that Dom Mintoff would soon leave – he had accomplished his dream of ensuring the British military base was gone and of launching the social welfare state. He himself would throw hints about this, though there were quite many people who suspected that this was the usual ruling alpha-male tactic of provoking reactions to smell out who was intending to undermine his leadership. A few (but they were less than vocal and very timid) thought Mintoff needed to bow out: his government had gone flabby, ministries had become clintelistic fiefdoms, and the Opposition Nationalists were making waves.

Quite a number of Labourites rooted for Minister of Public Works Lorry Sant as successor, but though he enjoyed substantial grass roots support, it would always remain in the minority as there were too many to oppose him, his style and reputation. Joe Brincat’s initial popularity during the first half of the 1970s had been consistently eroded within the party, some hinted at Mintoff’s behest. Wistin Abela attached to the Office of the Prime Minister and a leading light for Labour from Zejtun, though a papabile, was seen as at best a last ditch compromise figure and therefore attracted sub-optimal following. Lino Spiteri was still at the time Deputy Governor at the Central Bank and out of politics, which he re-entered as of the 1981 general elections.

In this situation, Mintoff took the initiative by proposing that Joe Brincat, then deputy leader party affairs would become Justice Minister and thereby relinquish his party role according to the MLP statute, and Dr K Mifsud Bonnici would take his place. The choice of Mifsud Bonnici was both surprising and astute.

He was practically unknown to the wider public, his low profile style and soft manner of speech were exactly the opposite of how Labour politicos used to operate, while his name and career (at least up to the mid-1960s) reeked of PN and the Church. Post the mid-1960s, he had swung left, became a trusted confidant of the GWU and through it had links with Labour, mostly as some kind of advisor. His presence had been totally capillary as one who really wanted to be of service – so if the wider public hardly knew him, local and national decision makers within the Labour Movement (party and GWU) knew him well and liked him very much, even if some doubted whether his qualities made for leadership material.

I guess that when KMB was nominated deputy leader of party affairs by mid-1980, possible future contenders for the leadership like Lorry Sant understood what was going on, but there was nothing much they could or wanted to do to turn the situation around. The 1981 election result made matters more complicated and (again this is my guess) their judgement was that they had best bide their time.

In my remembrance of how things developed, there was little to no overt resistance to KMB’s progress from deputy leader, to successor in waiting and then substantively to Prime Minister and party leader. In 1985, when although already installed as Prime Minister, Dr Mifsud Bonnici asked for a secret vote of endorsement at the MLP general conference which I then chaired, there was resistance to this. Most delegates opined a vote was not necessary and certainly not a secret vote. In line with KMB’s wishes, I ruled in favour of a secret vote. Lorry Sant then came from the floor to give me his open vote in favour, because otherwise any negative vote that was placed would be attributed to him, so he claimed in a loud voice.

It has often been said that in spite of relinquishing his power, Mintoff remained the leader with Mifsud Bonnici on the front line. How true is this?

To be honest, I have difficulties in replying. Mintoff did relinquish his post and power, but he still retained a leading role in the power structure. Dr Mifsud Bonnici was far from being the stooge right wing commentators tried to project him as. His strategy was clearly different from his predecessor’s and in substantial sectors, such as EU affairs. But though in many ways he was his own man, and had a formidable intellect and an equally formidable stamina, he did at times defer too much to what Mintoff wanted or said.

There were occasions, and they were quite crucial, when Mifsud Bonnici put his foot down, no matter what Mintoff opined, and his decision stuck, as in the final stages when Labour was about to accept the 1986 package that put an end to the political crisis resulting from the 1981 election result. On other occasions, he would immediately align himself with what Mintoff wanted, sometimes because their views coincided, at other times because (I think) Dr Mifsud Bonnici really believed that with his deeply entrenched roots in the Labour Movement, Mintoff’s intuitions could not be faulted by anyone.

So he evidently thought that Mintoff as President of the Republic would be a good idea, in both national and party terms and played along fully with the game of trying to secure such an outcome both pre and post 1987. In the latter period, his alignment with Mintoff on such matters as the issue over the Delimara power station was in my view, a huge mistake.

Next week: Alfred Sant on the bulk-buying system and the employment issues of the 1980s