The chief Scientific officer of the Plant Protection Directorate (PPD), Matthew Tabone, has told The Malta Independent on Sunday that the process of micro-propagation, that is, genetic cloning, is presently being conducted at the PPD in Attard and is salvaging endangered local plant species from going extinct.

Tabone, who forms part of the PPD's Conservation of Genetic Resources Unit (CGRU), spoke to this newsroom about this modern method of plant preservation and conservation, and detailed how genetic cloning or micro-propagation, is already saving very rare plant species from potential extinction.

During a visit to the PPD's facilities, Tabone showed how his unit has helped multiply the population of some extremely rare and endemic plants through its Plant Tissue Culture Laboratory (also referred to as the Tissue Culture Lab). This laboratory is typically called upon for intervention after an entity, such as the Environmental Resources Authority (ERA), struggles to propagate a certain plant enough through conventional means.

The Tissue Culture Lab, also known as the in vitro lab, is where such interventions take place, through which experts may "multiply plants by hundreds" and grow their population exponentially.

Produced in sterile conditions, selected rare plants are multiplied through a specialised scientific process after being deemed viable to grow into a plant and produce a next generation.

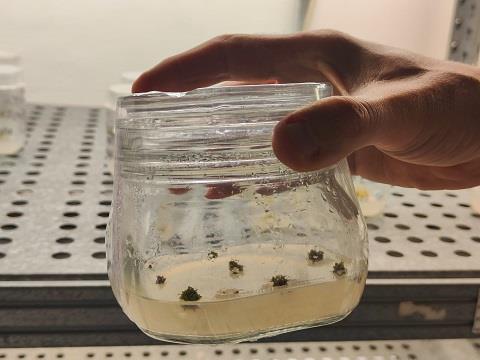

First, scientists fill up jars with an agar solution (a gelatinous substance filled with nutrients that promote plant growth) and place four little plant nodes inside each container, closing and leaving them inside. If the agar medium does not promote plant growth, then the scientists will need to amend its internal contents and start over.

If the plant nodes are growing, then after approximately one month, the agar is replaced so that the plant nodes can be replenished with more fresh nutrients. After growing taller and closer to one another, the scientists then divide the nodes to give themselves four to six plants from each one (depending on the nature of the plant species), before then placing the new segments in separate jars to replicate the process and continue growing the population.

Through this method of cultivation, the team within the CGRU can produce up to 30 distinct plants from a single starting jar.

Following sustained and sufficient growth, the plants are then extracted from these jars, potted and slowly acclimatised into their natural environments via greenhouses, screenhouses and shade houses, before then being sent out to grow in the natural environment. These acclimatisation stages, through the changes in environment, are a shock to the transferred plants, and therefore, are fragile moments within this process that leads to the natural loss of some lab-grown organisms.

Barring any setbacks, this entire process - from first replicating a plant in the laboratory to dispersing hundreds into the wild - takes around five to six months.

The CGRU's efforts have already resulted in some rare plant species having gone from just a single-digit number of found individuals in the wild to grosses available for dispersion back into their natural habitats.

Such was the case for five varieties of Sea Lavender (Limonium) plants and two species of mulberry (Morus) trees.

Once these newly-bred plants reach a mature enough stage, the Directorate then liaises with other environmental entities, such as the ERA and Ambjent Malta, for them to be dispersed in appropriate locations within the country's natural environment, for example in suitable Natura 2000 sites.

The chief Scientific officer added that plant and crop species can be ameliorated genetically (genetically modified for the better) via conventional breeding or through an internationally contentious exercise known as gene editing, through CRISPR technology. Despite existing reservations from experts around the world, Tabone personally believes that gene editing "is the future of this sector".

Limonium plants potted inside greenhouse (stage after jars in Tissue Culture Lab)

Limited Limonium - saving the Sea Lavender species

One highlighted example of these efforts was demonstrated through an ongoing collaboration between the CGRU and a PhD student through a project aimed towards revitalising the diminishing Limonium plant species. Together, they envisioned increasing their population through micro-propagation.

Tabone described that there are five different varieties of the Sea Lavender plant species across the Maltese islands: the Maltese Sea Lavender (Limonium Melitense), the Violet Sea Lavender (Limonium Virgatum), Lanfranco's Sea Lavender (Limonium Lanfrancoi), Zerapha's Sea Lavender (Limonium Zeraphae) and Narbonne's Sea Lavender (Limonium Seritonum).

"These five types of Limonium have very restricted distribution and are all endemic plants," he said. "Their populations are very, very limited."

Prior to this project, Narbonne's Sea Lavender was only observed in a single Natura 2000 site through eight found individual organisms in the entire country. Micro-propagation has helped the CGRU produce some 250 of these species.

Morus nigra (black mulberry tree)

More Morus

In the past, similar efforts were also undertaken to restore the decimated population of mulberry trees, specifically the black mulberry tree (Morus nigra) and the white mulberry tree (Morus alba).

Tabone described that in this instance, a micro-propagation project was initiated after a bug entered the Maltese islands through the importation of foreign logs, and found its way into the local natural environment, obliterating many large mulberry trees upon arrival.

"At the time, the government took the decision to help the growers to try and save the local genotypes present in Malta, but also help the growers by giving them these types of trees, available for the local market," Tabone said.

Given the rich value of these trees' fruit, it was "quite natural" to mass produce these trees via micro-propagation. Since then, the demand from growers for the cloning of these trees has reportedly plateaued, meaning that the scientists at the CGRU achieved what they were after.

Plant nodes growing in jars through micro-propagation

Furthering environmental conservation through Malta Gene Bank

On 18 May, it was announced that through a €3m investment, Malta was going to begin preserving indigenous and endemic plants and crop seeds via a national repository. This repository is referred to as either the National Plant Gene Bank or the Malta Gene Bank.

The building was financed by the government while all laboratory equipment and internal offices are financed by the European Union.

"The country felt the need to have a gene bank," he said. "A gene bank is a place where seeds and genetic material are stored for long-term storage."

Despite the building being inaugurated six months ago, the Gene Bank is still not yet in operation and is, so far, empty. Tabone told this newsroom that his team at the PPD is waiting for specialised equipment to arrive to from overseas before they can begin formally setting everything up.

Once this gene bank becomes functionable, the researchers at the PPD will be able to store a variety of these seeds and genetic material in liquid nitrogen, under a controlled temperature of -178°C. Barring any issues, this long-term conservation should be able to store these individual plant/crop species for around a century or more, according to Tabone. Currently, the Gene Bank contains one of just two liquid nitrogen generators on the island.

Once functioning, the Gene Bank will have a dual purpose - conservation and research. These efforts will be oriented towards the conservation of wild plant species as well as unique agricultural crops that are grown by local farmers.

"Over millennia, farmers have developed breeds and varieties that are unique to Malta," he remarked, "Unfortunately, this subject was seldom studied well. To this day, there are very few publications on this."

Chief Scientific officer of the Plant Protection Directorate (PPD), Matthew Tabone

Tabone stated "it is a big shame" that we have probably lost several unique varieties that have gone extinct in local agriculture following the passing of a farmer who solely cultivated them to life. He described that "these are intrinsically linked with farmers" and that in this local sector, it is a reality for rare varieties to die with their respective cultivators. Hence, he hopes for the Gene Bank to act as a catalyst for this literature gap to be filled by researchers.

"Our aim is also to try and find these varieties - food varieties, vegetable varieties, vegetables - all these sorts of agricultural connected varieties that are still existent," Tabone described. "It is in our national interest to conserve these species."

Elaborating on this, Tabone said that this subject is in our national interest due to the possibilities that can emerge from analysing the different genetic traits of particular plant species. Aside from long-term storage and research, the Gene Bank will also provide improved means to ameliorate existing species.

As an example, Tabone explained how a seemingly banal and unproductive seed may be of use if it contains some genetic traits that are useful for our ever-changing world, especially with respect to climate change. He stated that if such a seed is found to have traits suitable for drought, for example, the scientists at the PPD may collaborate with other entities to use these responsible genes to improve a more sought-after plant/crop, make it more productive and allow it to flourish commercially through the added natural resilience.

"The idea is that, in Malta at the moment, genetic analysis on plants does not exist," Tabone said.

Once the Gene Bank is set up and has its database filled up, the country will have a repository that will allow the CGRU to "have a complete picture of all the plants and crops that we have in Malta".

When asked about the benefits of this project, Tabone iterated that having these long-term storage facilities is a matter of food security and national security. He explained that if, hypothetically, wheat was to be decimated through a disaster or a pest outbreak, the Gene Bank could be of great use to replenish this damage.

By conserving this "unique genetic material" ex situ (off-site), the scientists at the PPD would be able to produce wheat safely through its Tissue Culture Lab or out in the natural environment if safe.

"The idea is that, in Malta at the moment, genetic analysis on plants does not exist," Tabone concluded.