LG: Ivan what is the concept behind these works?

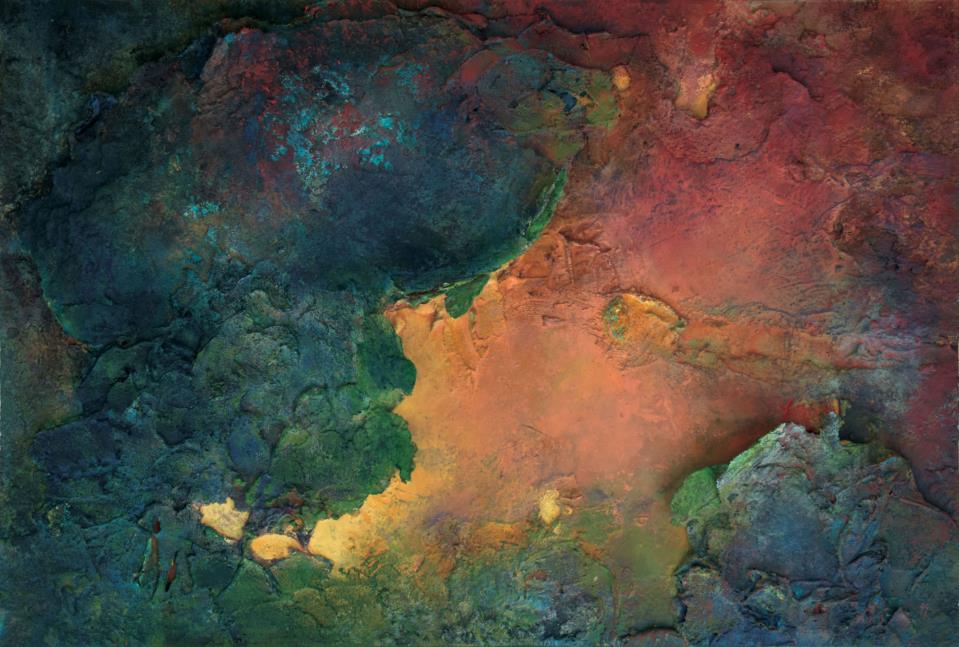

IG: In a nutshell, I tried to achieve beauty in imperfections. Here we don't see an even, perfect surface but rather vulnerable rough textured surfaces. I deliberately "destroyed" and "wounded" the surface and applied plaster and colour. The challenge of working the material itself was beautiful but the concept behind was even more so.

In the Japanese way of thinking of wabi-sabi there is the concept of kintsugi in which a broken piece of ware is put back together and beautified by means of a gold application where it was broken; the object then becomes more valuable than it was before it broke. I encountered this philosophy while working on this project and it matched my mindset. A piece of wood has less value if it is uneven or scratched with parts of it that are falling apart. In these works, something undesired is transformed and healed.

In these abstract pieces the wound is physical but in us, wounds are not superficial; they may be physical but are usually deep set, for example, they can be psychological: an injured ego, a damaged relationship. All that is damaged changes character. In this case, weak, wounded surfaces can become precious.

LG: Prof. Friggieri what do you think of these works?

JF: Let us start from a simple idea. Abstract art is not representational. It doesn't represent figure, landscape or still life. It doesn't deal with themes like The Crucifixion or The Nativity, which form the subject of so many paintings in the history of art.

So one would be taking the wrong approach to Grixti's works if one were to try to interpret them in the terms one uses to describe representational or figurative paintings. What one admires in these works is the technique used in their production, their compositional features, the material used and the way the artist uses it. Plato thought of mimetic art as an imitation or copy of the world as we perceive it, which was itself a copy of the ideal world of Forms. He saw representational art as twice removed from reality as he conceived it. His hostility towards art and artists in general was based on this metaphysical view which his student Aristotle radically disagreed with, and which we now no longer share. Even if, hypothetically, Plato's views were true of representational art, they would still not apply to abstract art, which is not representational in that way. What we admire in Grixti's works is his skill, the way he deals with the surface of the painting, the way he uses colours and shapes, and the other compositional features of the works.

In our conversation, Ivan used the word tferi, to wound, which is the title he used for the collection. Technically, he was "wounding" the surface, but he was also using that term metaphorically, with regard to the content of the painting, or the idea he was trying to convey. This is something he can talk about himself, much better than I can.

LG: Ivan, how did you get the idea of using this technique? You 'wounded' the surface. This makes everything very interesting. Can you tell us more about your technique and process of work?

IG: Prof. Friggieri "peeled" my concept layer by layer. The process of thought began in Poland at the University of Lublin. My tutor Piotr Korol limited us to an exercise in which we could use just one surface and colour. But then I went a step further and changed the surface and the limitations. The works are made of thick fibreboard. The surface was deformed with a chisel. Sometimes I even let the surface deteriorate in water; I also used already deteriorated surfaces. After chiseling, plaster coats, gesso and glue were applied... the surface changed: on certain materials colour was absorbed and on others it wasn't. The process became interesting but challenging. While creating these wounded surfaces I was filled with satisfied determination. Some of them were very challenging because I wanted to push them further to achieve a chanced but controlled effect. There was a struggle between leaving the colours to react naturally on the surfaces and controlling them. Then of course other elements of control were the selection of colours, the composition and perspective. This process of work then fits into a psychological, human, spiritual and material state, but if one just stops on the technique and sees wounds in the surface, that is also enough.

LG: Prof. Friggieri, in talking to Ivan, you were eager to know more about his technique. Why do you consider technique so important? How does it fit into Art theory?

JF: The ancient Greeks did not have the concept of fine arts as we use the term today. They used the word techne, plural technai, which meant skill, the same word they used for other kinds of work, like medicine, flute-playing, carpentry, and so on. Artists showed a special kind of skill, they were experts in the exercise of mimetic skills, in the sense we were talking about. They were good at making things. This is where the word poetry comes from: it is the skill of using language in a particular way. And this applies to the other arts as well. Skill is not, of course, the only thing one needs to be (or be called) an artist, but it is a crucial element nonetheless.

LG: Ivan besides technique, what else do you want your viewers to see without influencing them?

IG: Well, the physical, psychological and spiritual dimension merge in this project. Everything around us including us, is vulnerable. We can be damaged but also healed and revived. In part these works can refer to humanity and its brokenness or scars that need healing. Healing one's scars is usually a layered process which ends in self-discovery and consciousness that brings redemption. Past scars and human flaws are covered under various layers of time. There has to be a conscious acceptance of emotions; once these truths are revealed they are healed. When we confront our wounds and become aware of them, we begin to seek beauty within them.

LG: Ivan, are you an artist in search of beauty?

IG: Well, with this question I have to mention the spiritual aspect as well. I think it is an intrinsic tendency to be attracted to beauty, however, real authentic beauty is hardly ever achieved. In different eras and civilizations, art and painting had different objectives, aspirations, status and style but I think beauty was a common factor. Kalos is a Greek word, that means beautiful, good and perfect. A certain formula or code can be observed in nature which refers to the origin of beauty and harmony. The Greeks applied this with the golden ratio and Fibonacci also developed his formula that can be seen all around us, in how nature behaves and takes shape. Yet harmony is not only in shape or proportion, it is also in colour.

I agree with Dostoyevsky who says that "beauty will save the world" and also with Jordan Peterson "beauty is a pathway towards God". I believe that beauty and perfection have divine qualities and that God, the primum movens, is unique, divine and consequently beautiful and perfect. But at the same time as a believer, I also affirm that together with love, beauty is a very profound term. Furthermore, Jesus on the cross transformed and dignified wounds and suffering into something beautiful that saves. "With his wounds he saved the world." This is spiritual concept that is parallel to this project.

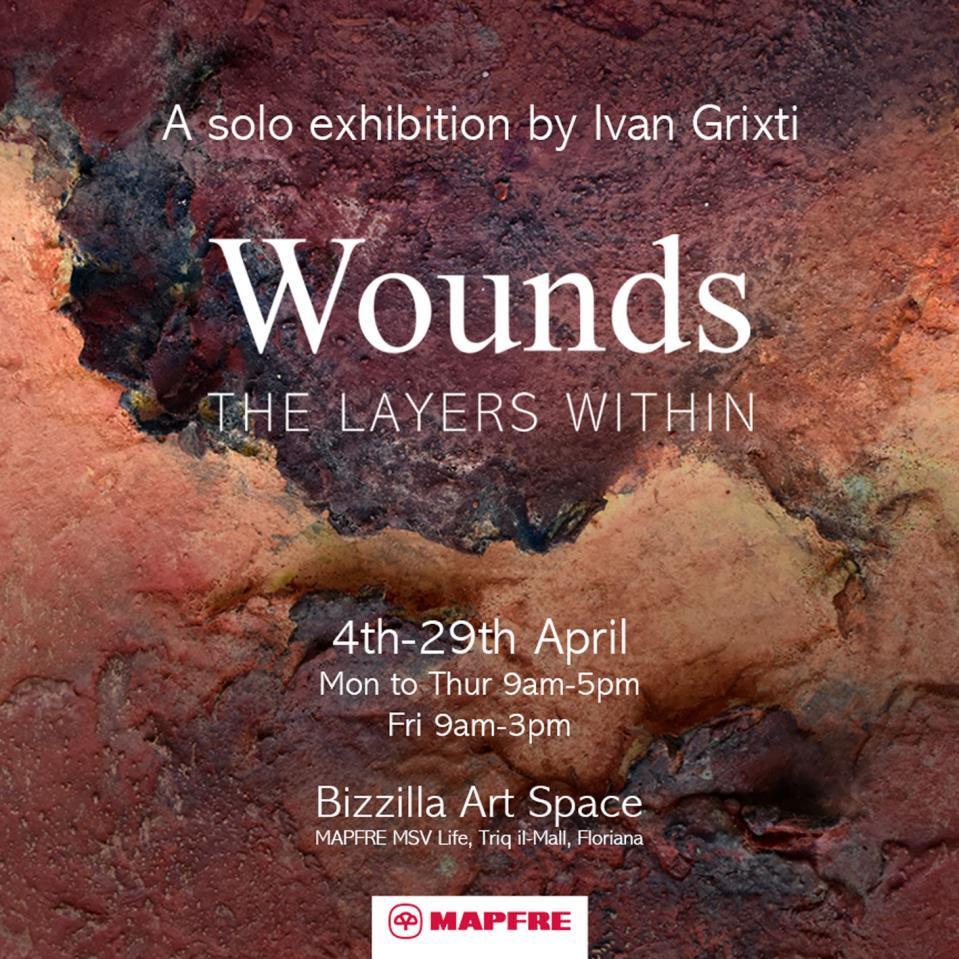

The exhibition Wounds - the layers within runs from 4 to 29 April at Bizilla Art Space, Mapfre MSV Life, Triq il-Mall, Floriana. It can be viewed from Monday to Thursday between 9am and 5pm and Fridays between 9am and 3pm. Meet the artist dates will be published on the artist's Facebook page https://www.facebook.com/kontempartgallery