Malta's history has been pushed back by 1,000 years in a discovery that is rewriting the islands' pre-history, as scientists have found new evidence that shows that hunter-gatherers voyaged at sea to Malta, well before the first farmers.

The research, led by Professor Eleanor Scerri of the Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropology and co-investigator Professor Nicholas Vella from the University of Malta, uncovers an entirely new period in Malta's timeline, pushing back the first signs of human life by at least a millennium, around 40 generations, and officially adding the 'Mesolithic' era to the country's story for the first time, pre-dating the Neolithic period.

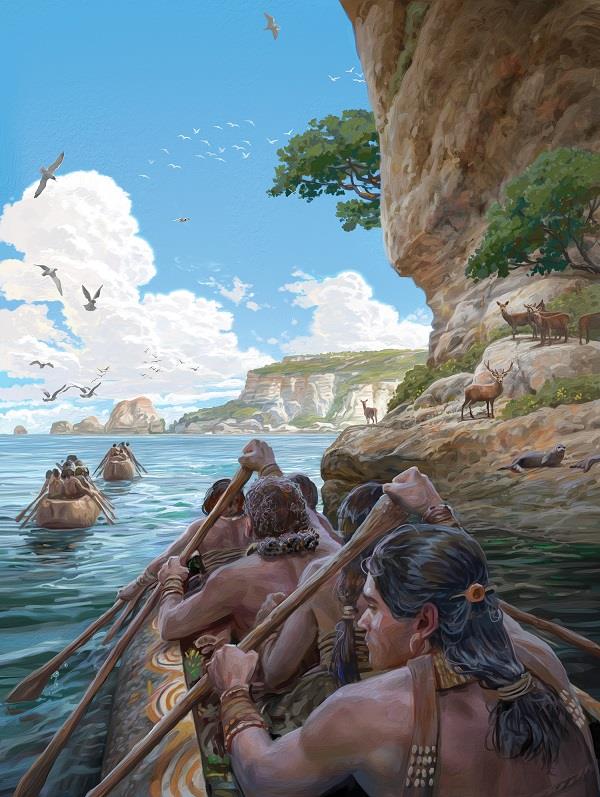

In a paper published in Nature on Wednesday, new evidence showed that hunter-gatherers were crossing around 100 kilometres across open Mediterranean waters to reach Malta, likely in simple dugout canoes, with a speed of about 4km per hour, breaking prehistoric seafaring records.

The discoveries were made by a scientific consortium at the cave site of Latnija, in the northern Mellieħa region, where using state-of-the-art methods in archaeological science, researchers found traces of humans in the form of their stone tools, hearths, cooked food waste, and beds of ash

The site, which is found behind Paradise Bay, has remained archeologically preserved, with all its deposit remaining untouched.

The study, which consisted of site excavation over five years, revealed that humans were living in Malta from at least 8,500 years ago, on a diet of wild food including birds, fish, marine mammals, and local species.

Photo: Huw Groucutt

Through carbon-dating, researchers were able to establish the dates of ancient DNA recovered from sediments and carried out research with protein fingerprinting of bone fragments, and temperature and rainfall records from fossil water geochemistry tapped in cave formations, Scerri said.

"We found abundant evidence for a range of wild animals, including indigenous Red Deer, long thought to have gone extinct by this point in time. They were hunting and cooking deer alongside lizards, tortoises and birds, including some that were extremely large and extinct today, as well as foxes" Scerri said.

Researchers found thousands of animal bones, many of them burned, Scerri said. She added that these diets are typical of other Mesolithic hunter-gatherers who had lived on coastal Sicily but were very different to the diets of farmers who came later.

Vella said that these seafarers would have led to over several hours of darkness in open water, and these hunter-gatherers would have relied on sea surface currents, prevailing winds, the use of landmarks, stars and other wayfinding practices.

Photo: Huw Groucutt

The Professors said that remote islands like Malta were long thought to be among the last frontiers of untouched nature, inaccessible to humans until the agricultural revolution.

Europe's last hunter-gatherers were seen as unwilling or unable to get to small and remote islands as they usually need to exploit large areas to hunt and gather wild foods without depleting resources.

Navigating very long sea-distances was therefore thought to be either beyond their capabilities, or not worth the attempt.

However, this discovery upended those views, as evidence has shown that Malta's first people were not the farmers coming from Sicily around 7,000 years ago, who had seemingly found an untouched landscape by humans, but hunter-gatherers who arrived a thousand years earlier, surviving on a rich and now-lost ecosystem of extinct animals and species once believed never to have existed on the islands, Vella said.

"We have to revise the curriculum and amend our history books with these findings. This project is important, not only for Malta, but also more widely, as it is a complete first for hunter-gatherers to cross the Mediterranean, breaking the record of the longest distance travelled in the Mediterranean. This will have repercussions on what we know on the Neolithic period," Vella said.

The team also found clear evidence of a largely mixed diet, including the exploitation of marine resources, such as remains of seal, sea snails, various fish, including grouper, and thousands of edible marine gastropods, crabs and sea urchins, all found indisputably cooked.

The discoveries also raise questions about the extinction of endemic animals in Malta and other small and remote Mediterranean islands, and whether distant Mesolithic communities may have been linked through seafaring, Scerri said.

Photo: Eleonor Scerri

"The results add a thousand years to Maltese prehistory and force a re-evaluation of the seafaring abilities of Europe's last hunter-gatherers, as well as their connections and ecosystem impacts," Scerri said.

She added that this Mesolithic period is the final stage of hunter-gatherer prehistory, who were able to survive the last Ice Age. They used tools made of local limestone and were able to exploit resources from the air and the sea, overcoming land size limitations, she said.

"The site is now being secured, and this is just the beginning. There is ongoing research and more jaw-dropping results in the pipeline, which are being verified," Scerri said.

"Our discovery connects Malta with a much deeper human prehistory, it roots Malta to the story of humanity itself," Scerri said.

She added that there is global interest in the research programme, by the BBC, National Geographic, the New York Times, and many others.

A documentary is also being produced to showcase Malta at its best, and appeal to a higher-spending, culturally aware demographic, Scerri said.

Dr James Blinkhorn of the University of Liverpool and MPI-GEA is one of the study's corresponding authors.

The research was supported by Malta's Superintendence of Cultural Heritage and funded by the European Research Council and the University of Malta's Research Excellence Award.

Credit: Daniel Clark