For over two centuries, the traditional regatta, held annually on the 8th of September in the Grand Harbour, has been an intensely and passionately contested competition between the Cottonera and Marsamxett districts, now known as clubs. Even today, this rivalry is strongly felt among the devoted supporters of the opposing clubs during the fiercely competitive races, which stretch from the starting point at Ras Ħanżir to the finishing line at the Customs House.

Long before Marsamxett was organised into a regatta district and began taking part in this spectacular event in the mid-nineteenth century, the old cities of Senglea, Bormla (Cospicua), and Birgu (Vittoriosa) - enclosed within the Cottonera Lines, had already laid claim to a long-standing tradition of participation in competitive boat races.

The origins of boat races in the Grand Harbour date back to the late 1620s, specifically between 1625 and 1630. This tradition is widely attributed to the Senglean boatmen and fishermen. Unfortunately, no surviving document confirms the exact year these races were first held. However, a significant clue comes from a 1642 historical document retrieved from the archives of Bormla's Parish Church, linked to the Fraternity of Our Lady of the Rosary. This petition, dated 2nd September 1642, was submitted by Mattino Fiteni, head of the fraternity, to Fra Giovanni de Vihovel Nigraponte, Chancellor of the Order. Fiteni requested permission on behalf of the fraternity to organise a boat race on the feast day of Our Lady of the Rosary (7th October), citing that the people of Senglea already held such races annually.

The Chancellor reviewed the request and forwarded it with his note to Grand Master Antoine de Paule (1623-1636), who approved the event on 9th September. It is likely that the Chancellor's note was simply a reminder that the race Fiteni referred to was the Porto Salvo boat race, held annually on 2nd July to commemorate the feast of the Visitation of Our Lady to Saint Elizabeth.

Why do some historians suggest 1625 -1630 as the period when these races began? The tradition of the first races being organised by Senglean boatmen and fishermen is closely linked to the church dedicated to Our Lady of Safe Haven (tal-Portu Salvu), now known as Saint Philip's Church (San Filippu), located around 200 metres from the Gardjola Garden and built in 1596. During the first pastoral visit by Bishop Baldassare Cagliares (1615-1633), the boat races were not mentioned, perhaps because they were not yet established or were not considered religiously significant. Fortunately, in later years, these races were consistently recorded by bishops in their pastoral visits to the church, continuing until the early nineteenth century.

Considering the 1642 document by Mattino Fiteni, in which the Senglea boat race is referred to as already being an annual tradition, and the absence of any reference during Bishop Cagliares's 1622 visit, one can reasonably conclude that the races began sometime between those years - most likely in the mid-to-late 1620s. Over time, this race became known as the Porto Salvo Regatta. As for the boat race of Birmula/Burmula (now Cospicua), this was held on 7th October 1642 in honour of the feast of Our Lady of the Rosary (Tar-Rużarju).

While we still lack documentation identifying the exact location, it is likely that the race was held near the town itself, possibly in Porta delle Galere or Galley Port - known today as Dockyard Creek. It remains unclear whether these races were held annually, and if so, how regularly. Knowing that October is often a stormy month, it is reasonable to assume that weather conditions may have sometimes disrupted these events.

Naturally, the origin of this tradition raises many questions - how these races began, how they were organised, and how they developed over time in the Grand Harbour. To answer these questions, one must explore the broader historical context, including the cultural and religious practices of the time. For centuries before the arrival of the Order of St John in Malta, essential goods such as wheat, wine, and timber were imported from Sicily.

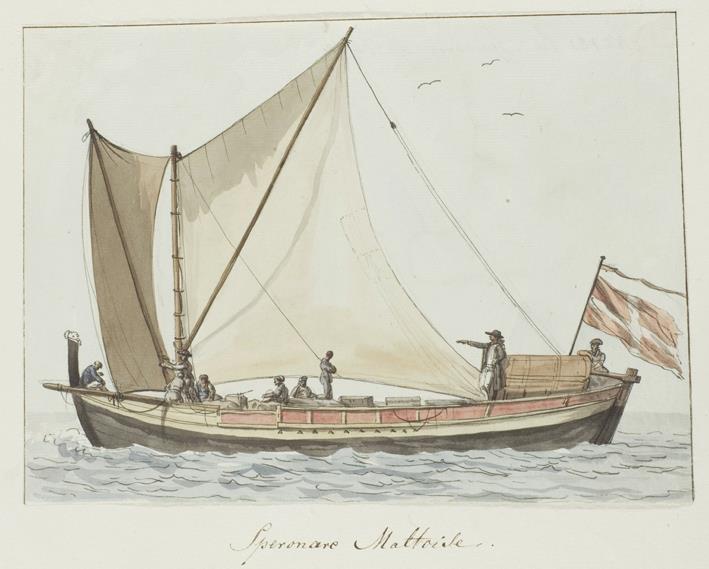

Some passengers, including merchants and relatives of Sicilian residents, would cross the channel on Maltese boats that even predated the traditional Speronara (xprunara). The arrival of the Order brought expanded work opportunities for local craftsmen in the arsenals and opened new trading routes for Maltese merchants, who began to travel beyond Sicily to cities like Marseille, Naples, and Venice to sell local goods and form new commercial.

Regarding the origins of these boat races, two plausible and historically grounded theories are often proposed. One theory suggests that Senglean boatmen and fishermen were inspired after some locals - possibly sailors aboard Maltese vessels or businessmen visited Venice in early September and witnessed the traditional boat races along the Grand Canal. Enchanted by the rivalry among the Venetian gondoliers and the festive atmosphere, these Maltese returned home with the idea of replicating the spectacle in the Grand Harbour. Another possibility is that Venetian sailors serving on the Knights' galleons, upon observing the various passenger and fishing boats in Malta's harbours, encouraged local boatmen and fishermen to organise races similar to those held in Venice and other Italian ports.

Regardless of which version is true, it is believed that some enthusiasts approached the rector of the Church of Our Lady of Safe Haven (Portu Salvu) and requested permission to organise a boat race in the harbour as part of the external festivities for the feast of the Visitation of Our Lady to Saint Elizabeth, celebrated on 2nd July. The rector welcomed the idea, perceiving that such an event could elevate the popularity of the parochial feast among residents of nearby towns and villages. He pledged to cover the costs of the race, including flags for the winners, using donations received at the altar of Our Lady of Safe Haven.

Over time, the Senglea parochial boat race, known as It-Tiġrija tal-Porto Salvo, became fiercely competitive among the local boatmen and fishermen, quickly gaining popularity within the harbour community. At its height, a wide range of traditional passenger and fishing boats,including xprunari, ferilli, barkazzi, kajjikki, braken, and dgħajjes tal-passtook part. Some of these boats were rowed with paddles; others used sails. The race was held annually on 2nd July in the Grand Harbour, running from beneath the Gallows Tower (Fort Ricasoli) to Senglea Point. It began with the sound of a petard and was supervised by the church rector and an appointed jury tasked with ensuring all crews adhered to the rules.

The popularity and rivalries of parochial boat races between the local crews

This local regatta became a spectacular annual event, drawing crowds from surrounding cities and towns. On the feast day of Our Lady of Safe Haven, spectators would cram Senglea Point, the Valletta bastions, the Quarry Wharf (Xatt il-Barriera), the rocks under the Castrum Maris (later Fort St Angelo) and on boats along the racecourse. The winning boats were confirmed by two jury members in a boat, in the presence of the Viskonti, the Captain of the Rod (il-Kaptan tal-Virga or il-Ħakem), and the Night Captain of Senglea (il-Kaptan ta' bil-lejl tal-Isla) in a separate craft. After Vespers, the church rector presented linen flags (imported from Messina) to the winning crews in the church square, to the cheers of the rowers and spectators.

Naturally, such competitions bred intense rivalries - even among crews from the same town. Sadly, many races saw serious collisions and bitter arguments, sometimes escalating into physical confrontations. During a private audience with Bishop Davide Cocco Palmieri (1684-1711), the then-rector of the Church of Porto Salvo, Father Xmun Schembri, expressed concerns over the race's future. He complained that the annual income from the altar was insufficient to cover the regatta's costs and that ongoing feuds between crews were turning the event from one of celebration into one of hostility. Another problem was that every crew expected to receive a Palju (linen flag), regardless of whether they won.

Bishop Palmieri, while acknowledging the regatta's deep-rooted popularity and its capacity to draw crowds from across the harbour area, noted that the funds used for organising the race could serve other community needs. However, rather than cancel the event, he urged Father Schembri to continue supporting it with some reforms: the number of races should be reduced from 12-14 to just six categories, only the winners should receive a flag, and all boats in every category must be of equal weight. Unsurprisingly, these reforms were unpopular. Some rowers withdrew from the race entirely, while others participated under protest.

There were periods when the regatta lost public interest,often due to the absence of well-known rowers, reduced participation across boat categories, or disruptive incidents like boat collisions and violent altercations at the finish line. Despite these setbacks and financial difficulties, the race continued to be held annually, except in years when the harbour was congested with M merchant vessels. In one such instance, recognising the financial strain on the rector and organisers, Maltese ship captains began donating a few scudi upon entering port with merchandise. Local businessmen, eager to preserve this cherished tradition, also contributed funds to cover the loss. Their efforts helped ensure the survival of this cultural event.

By the mid-eighteenth century, the Porto Salvo boat race experienced a revival. It became so popular that it was perceived as a national event. During regatta days, the Grand Harbour was filled with small crafts carrying spectators who eagerly watched the fiercely contested races in a lively and festive atmosphere. The Grand Master himself would cross the harbour by gondola from the Custom House to Senglea Point, where he watched the races and presented linen flags to the winners. After the regatta, the Grand Master would host refreshments at the Casa Magistrale for judges, magistrates, notaries, and other dignitaries. The races remained widely celebrated and attended for many years.

Unfortunately, around 1770, this traditional regatta came to a halt. Occasionally, the harbour's congestion with trading vessels, brought on by periods of economic slowdown made it impossible to hold the races. This suspension deeply disappointed not only the boatmen and fishermen but also the thousands of spectators who traditionally lined the harbour's bastions and wharves to cheer on their crews.

Gozitan historian Giovanni Pietro Francesco Agius de Soldanis (1712-1770) mentioned the regatta in his writings. Meanwhile, Father Ignazio Saverio Mifsud, concerned about the race's decline, lamented in his journal Il Giornale Maltese in 1757 that he did not know when this beloved event would be revived. Thankfully, by the early nineteenth century (circa 1806-1808), the regatta re-emerged, alongside other races - such as the one in Kalkara. In one documented case, Father Paul Camilleri, on behalf of residents of Tas-Salvatur, appealed to Civil Commissioner Sir Alexander John Ball for permission to hold a boat race on 28th September in honour of Saint Liberata, the local patron saint. Permission was granted, with the condition that the organisers inform port authorities to ensure proper supervision. While it's believed the race took place in Kalkara Creek, no further documentation has been found confirming its exact location or whether it became a regular event.

As for the Porto Salvo race, the outlook was more positive. A group of businessmen, recognising that interest in the regatta was fading, sought permission from the civil commissioner to organise the race that year and in subsequent years. Permission was granted under the same conditions as the Kalkara race. Although the regatta experienced interruptions, it endured, and thanks to community support and determination, this historic tradition lived on.

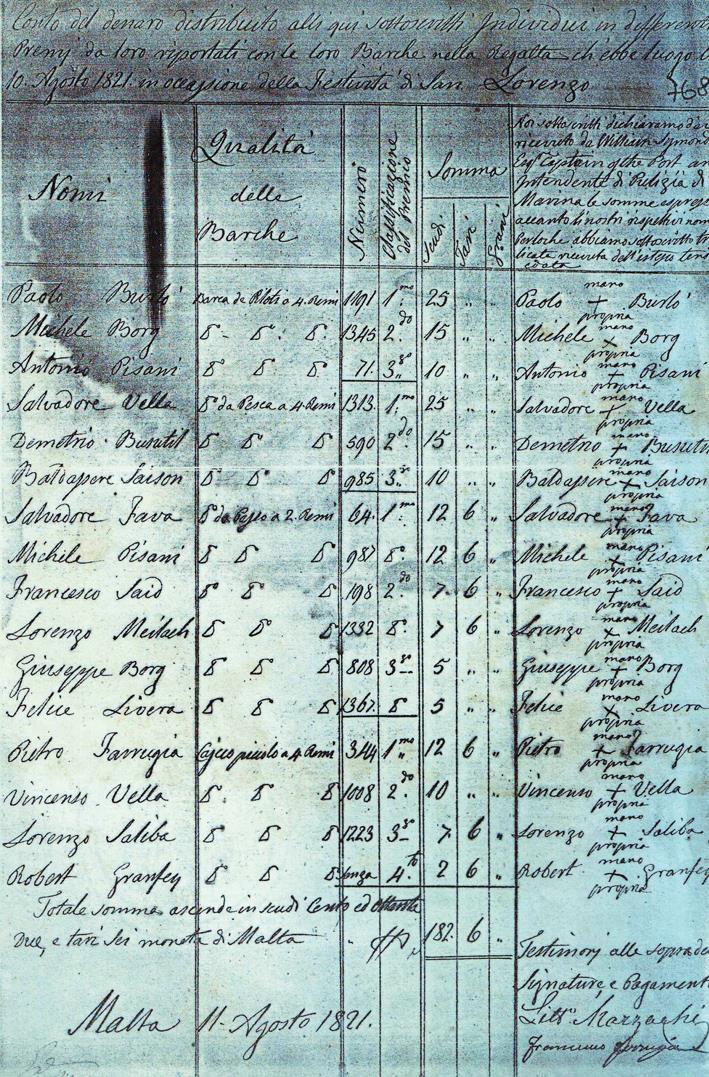

Another historical boat race associated with the city of Birgu (Vittoriosa) is recorded as having been held on the 10th of August 1821. Historical documents related to past boat races provide some insight into how this particular event came into being. On 18th June 1815, the British and their allies defeated Napoleon Bonaparte's French forces at the Battle of Waterloo. In Malta, the local British administration organised a number of festivities to commemorate this victory. One of the more prominent celebrations was the traditional Maypole, held in Palace Square in Valletta. For many years, this event remained a popular choice to mark the day, drawing large crowds to the capital. However, the Maypole event often turned unruly, with intense competition leading to injuries during the scuffles that broke out among participants trying to claim prizes.

In 1821, concerned about public safety and the violent incidents at the Maypole festivities, the governor prohibited the celebration for that year. Instead, he proposed that a boat race be held on the 10th of August, the feast of Saint Lawrence. So far, historical sources indicate that this race, whether it was a parochial race or not was only held once.

Part 2 will be published in the following weeks