As a fresh shake-up – the second in as many years – appears imminent at the Vatican Bank, Maltese economist Joseph F.X. Zahra, entrusted by Pope Francis to serve in two entities seeking to reform the bank and the Vatican’s economic affairs, is facing accusations of being at the centre of a conspiracy.

According to sources which spoke to Italian newspaper Il Giornale and news magazine L’Espresso, Mr Zahra is heading a so-called “Maltese lobby” which is seeking to gain control over the Vatican Bank – whose official name is the Institute for the Works of Religion (IOR) – for their financial gain.

When contacted by The Malta Independent, Mr Zahra categorically rejected the accusations, but also said that they were to be expected given his involvement in the reform process of a financial institution whose history has often been marked by controversy.

“A clear mandate for reforms was given to the Reform Commission by Pope Francis last year. Sadly these are the expected reactions that one gets during a reform process. Experience has shown that a price one pays in any reform is that of fabricated stories and other allegations that are aimed at eroding credibility of the reform process.”

Mr Zahra stressed that he was not in a position to comment on the workings of the two entities the Pope appointed him to serve in, but a report on La Repubblica – a sister newspaper to L’Espresso – suggests that he may have been caught up in the crossfire as factions within the Holy See are divided over the direction the reforms should take.

The ‘Maltese lobby’

Mr Zahra was already one of the five members of the International Audit Committee of the Holy See and the Vatican state before receiving two further appointments from Pope Francis.

On 18 July 2013, the pope created the 8-member Pontifical Commission for Reference on the Economic-Administrative Structure of the Holy See, and Mr Zahra was appointed as its president and legal representative.

According to an official statement, the commission was tasked studying “the organisational and economic problems of the Holy See, in order to draft reforms of the institutions of the Holy See with the aim of simplification and rationalisation of the existing bodies and more careful planning of the economic activities of all the Vatican administrations.”

Mr Zahra earned another papal appointment last February, when Pope Francis established the Holy See’s Secretariat for the Economy and appointed a 15-member Council for the Economy to draw up policy guidelines and analyse its work.

The council consists of eight cardinals – including Munich Archbishop Reinhard Marx, who was made the group’s coordinator – and seven lay experts, including Mr Zahra, the group’s vice-coordinator.

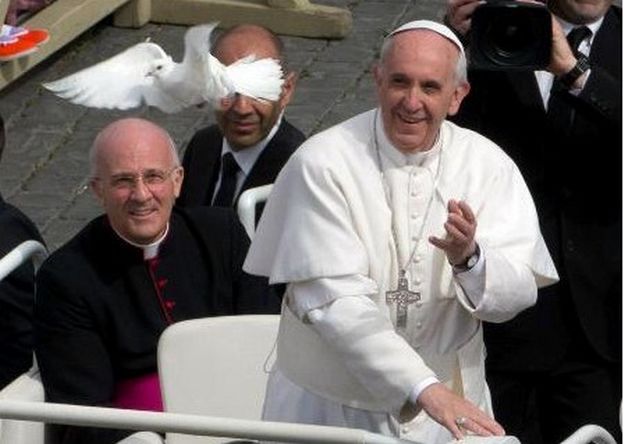

(Mgr Alfred Xuereb, sitting behind Pope Francis)

Another Maltese occupies a prominent position within Secretariat for the Economy itself, which is headed by Australian Cardinal George Pell: Mgr Alfred Xuereb, the Pope’s personal secretary, was made its secretary-general. Mgr Xuereb also serves as the Pope’s delegate on the commission presided over by Mr Zahra, and the Pontifical Commission for Reference on the Institute for Works of Religion, which was instituted in June 2013.

But Mr Zahra is the only Maltese member of the alleged “Maltese lobby:” the other two are Frenchman Jean-Baptiste de Franssu and Italian professor Francesco Vermiglio. Both men are members of the Council for the Economy, and the former also forms part of the pontifical commission Mr Zahra presides on.

The common link between the three, L’Espresso alleges, is the company founded by Mr Zahra – Marketing Intelligence Services Co Ltd, popularly known by the abbreviation Misco – and its subsidiaries.

But claims of any long-standing ties between Mr de Franssu and Mr Zahra appear to be baseless: the two only appear to have met after both were appointed to the same pontifical commission. The Frenchman’s only apparent link to Misco is his participation in a conference which was organised by Misco Directors’ Network Ltd in November 2013, four months after the establishment of the commission: he had never been, as L’Espresso and Il Giornale claimed, a manager of the company, nor otherwise involved in Misco or any of its subsidiaries.

Mr Zahra and Prof. Vermiglio, on the other hand, are known to be friends: during Mr Zahra’s term as Bank of Valletta chairman, Prof. Vermiglio was appointed to the bank’s board of directors as the representative of the Banco di Sicilia, which held a 14.56% stake in the bank at the time.

Prof. Vermiglio had invited Mr Zahra to address conferences at the University of Messina, and Mr Zahra subsequently lectured at the university part-time for a number of years, stopping when he became chairman of the National Euro Changeover Committee.

The two men are also linked through Misco Advisory Ltd, a joint venture between Misco and Studio Vermeglio: both are directors of the company, which is non-operational at present.

This partnership was seized upon by L’Espresso, which suggested that it – or Misco, which it described as a “financial consultancy” – could be utilised to shift capital into Malta if the “Maltese lobby” gets its way.

But this seems unlikely, not least because Misco is not a financial consultancy firm: it has no licence to do so. Among other things, the company and its subsidiaries engage in market research, business consultancy, accountancy, EU consultancy and training, but not financial services.

(Ernst von Freyberg)

Vatican divided over bank’s next steps

Claims of a Maltese lobby have surfaced as reports suggest that the IOR’s president, German businessman Ernst von Freyberg, is set for an imminent departure from the bank. Sources who spoke to the Boston Globe confirmed that this was the case, but disagreed whether this was a routine part of restructuring efforts or whether this was due to alleged irregularities.

What L’Espresso and Il Giornale have charged is that Mr Zahra and his allies are seeking to gain influence – and access to funds – by installing Mr de Franssu as Mr von Freyberg’s replacement.

The German banker was only appointed president of the IOR on 15 February, 2013, in what was to be one of Pope Benedict XVI’s final appointments before his resignation later that month.

One of Mr von Freyberg’s most notable efforts at the helm of the bank was the commissioning of an independent review of its account holders on May 2013, an initiative which led to the bank asking some 1,400 customers to close down their accounts, as they did not fit into the categories of clients the bank was allowed to have.

La Repubblica, meanwhile, suggests that cardinals are divided over the way forward for the bank, with Cardinal Pell reportedly leading the faction pushing for a shake-up of the Vatican’s financial institutions – including appointing a new president of the IOR.

It also reports that another faction, led by Italian cardinals Domenico Calcagno and Giuseppe Versaldi, is resisting the Australian cardinal’s plans, apparently in favour of a more cautious approach.

Mr Zahra, on his part, is reported to be close to Cardinal Pell: whether this perceived closeness has spurred the conspiracy theories centring on him is anyone’s guess.

Bank’s chequered past

But then again, the Vatican Bank’s past, often tainted with scandal and controversy, does make it somewhat easy to imagine that shadowy schemes and conspiracies are taking place. In fact, Pope Francis’ efforts to overhaul the Vatican’s financial and economic affairs – including through the establishment of the entities Mr Zahra forms part of – can be viewed as a reaction to its tarnished reputation.

The IOR’s origins date back to 1887, when Pope Leo XIII established the Commission for Works of Charity, which was transformed into the Administration for the Works of Religion (AOR) in 1908, during Pope Pius X’s reign.

The AOR was subsumed into the IOR when it was established by Pope Pius XII in 1942. Its statutory purpose is “to provide for the custody and administration of goods transferred or entrusted to the Institute by physical or juridical persons, designated for religious works of charity. The Institute can accept deposits of assets from entities or persons of the Holy See and of the Vatican City State.”

The bank’s surplus is at the disposal of the Holy See: its 2013 annual report – the first annual report the bank ever published, at the behest of Mr von Freyberg – shows that in 2012, the IOR registered a profit of €86.6 million, and gave a contribution of €50 million to the Pope.

(Michele Sindona)

But the bank’s reputation has been heavily dented after it brought in Michele Sindona as a financial advisor in 1969, in a bid to diversify its holdings. Mr Sindona’s own financial empire grew as he channelled part of the Holy See’s investments into it, only for it to collapse in 1974, causing the IOR losses reported to be in the region of $30 million.

Mr Sindona was convicted of fraud, and was eventually jailed for life for ordering the 1979 murder of Giorgio Ambrosoli, the lawyer who was commissioned as liquidator of his banks: he died after drinking poisoned coffee while serving out his sentence in 1986.

Another notorious scandal – one which inspired the plot of The Godfather Part III – centred around the 1982 collapse of the Banco Ambrosiano, a Milan-based bank which was part-owned by the IOR.

(Roberto Calvi)

Fraudulent practices had long been suspected before the bank collapsed, and were corroborated in 1981 when the police raided the office of the Propaganda Due masonic lodge, which included bank president Roberto Calvi – who had been dubbed God’s banker by the press and who had overseen an apparent stellar rise in the bank’s fortunes.

Mr Calvi was sentenced to four years’ imprisonment, but was released pending an appeal, keeping his position at the bank in the process. But when it was discovered that the bank could not account for 1.2 trillion Italian lira, he fled the country using a false passport, only for his body to be found hanging beneath London’s Blackfriars Bridge in an apparent attempt to conceal his murder. Dozens of people were eventually convicted of fraud over the bank’s collapse.