Outgoing EU Health Commissioner Tonio Borg is ruling out a return to Parliament, but he is ready to contribute to the Nationalist Party in other ways. The 57-year-old's term as Commissioner ends next Saturday, when the new Juncker Commission formally takes office.

It is not unusual for commissioners to participate in national politics after their term is over. Former commissioners who returned to active national politics include Lithuania's current president Dalia Grybauskaite, former Commission President and Italian Prime Minister Romano Prodi, and fellow Italian Franco Frattini, who left the Commission to become Foreign Minister in 2008.

Dr Borg insists that he would not be emulating their example. After over 30 years' experience - he started contesting general elections in 1981, and made it to Parliament 11 years later - Dr Borg says that his active political participation was a "closed chapter."

Dr Borg does have other plans in mind in the near future.

He plans to return to lecturing public law at the University of Malta next month, stating that he missed doing so. While Maltese ministers are allowed to lecture at university, European Commissioners cannot take on any other work, and Dr Borg went on unpaid leave for the duration of his term in office.

Next month, Dr Borg will also be publishing his first book, Nidħqu bina Nfusna, in which he recounts various humorous anecdotes about local MPs - past and present.

However, he emphasises; "I do not see myself returning to Parliament at this stage; I think that there are enough competent persons there."

This, he makes clear, does not mean that he has distanced himself from the PN, although obviously, he has not been actively involved in it during his term in Brussels.

"I have not changed my principles simply because I moved here," he states, pointing out that according to the party's statute, he is a member of its general council for life, and does not intend to renounce this privilege.

"And if the party seeks my assistance, I will be happy to provide it."

Dr Borg said that the ongoing reforms taking place at the PN was a process that needed to take place, although he adds that it is too early to gauge their effect.

But he dismisses any suggestions of a party in deep crisis, stating that it was only a matter of time before the PN returned to the Opposition benches, and that this was not the end of the world in itself, particularly after the party spent "25 years minus 22 months" in government.

"Time in Opposition is an excellent time for a party to reform itself," he points out.

After the sudden resignation of John Dalli, the nomination of Tonio Borg - the deputy prime minister and one of the most politically experienced members of government - was perhaps an obvious choice for the government.

As it turns out, the media made the right guess before he actually found out.

"When rumours that I would be succeeding my predecessor surfaced, I was ready to issue a denial," he maintains. "But then the Prime Minister called and said that I was required to take up the post, because there was the need to show that we could present a Commissioner who was ready to work."

Dr Borg concedes that it was not easy to accept - "I was happy to be where I was" - but recognised that becoming an EU Commissioner was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.

His reputation as a conservative politician preceded him - an MEP called him a dinosaur during his hearing, and a political group opposed him for his "antediluvian" - and he describes the hearing as a "baptism of fire."

In retrospect, however, he is almost pleased that this was the case: "everything that followed appeared easy in comparison."

The Commissioner adds out that one of his greatest satisfactions was to see several MEPs who had voted against him thank him for his contribution further down the line.

"The first thing I did as a Commissioner was to approach those who had not voted for me to assure them that I would be a truly European Commissioner and that I was ready to receive their suggestions," he maintains.

"I have nothing against those who may have been misguided in my regard."

Dalligate

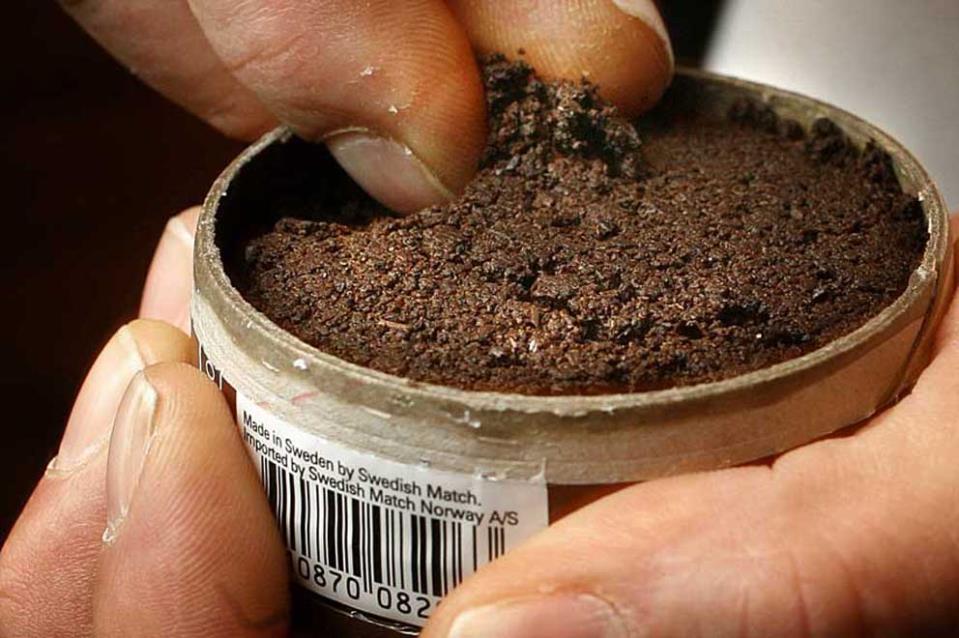

But Dr Borg continues to steer clear from commenting on the circumstances which brought him to the European Commission in the first place: Mr Dalli's resignation after a manufacturer of snus - a form of smokeless oral tobacco native to Sweden and illegal in the rest of the EU - claimed that an associate of his asked for a bribe to repeal the EU ban on the product.

Dr Borg even carefully refers to Mr Dalli as "my predecessor" throughout the interview: in fact, he has deliberately avoided commenting on Mr Dalli's case - which, he clarifies, he only found out about when it was made public - from the outset.

"Otherwise I would have spent my term living in the shadow of something I had absolutely no involvement in," he explains.

"I had my reasons - not excuses - not to comment in any way, particularly after the court cases began... I concentrated on the work at hand, and I think that this is what my predecessor, as well as my successor, would have wanted me to do."

Because of the circumstances, of course, his most immediate priority was ensuring that the tobacco directive at the heart of the controversy went through. To avoid any undue accusations of impropriety, he deliberately made no changes to the directive he had found on his desk.

The directive was thus adopted by the Commission just three weeks into Dr Borg's term in office, and his main objective then was to ensure that it came into force as soon as possible. The process was concluded in record time: the revised Tobacco Products Directive - replacing one adopted in 2011 - came into force last May.

MEPs most susceptible to tobacco lobbyists

While the Commission is the only EU institution empowered to propose laws, it is up to MEPs and member states to approve them - and to revise them as they did so. The risk, therefore, was that the revised Tobacco Products Directive would be diluted to the point of becoming practically worthless, if not make things even worse.

One might expect that member states - particularly those which are home to a significant tobacco industry - would seek to weaken the laws, whereas MEPs, as the direct representatives of EU citizens, would be more inclined to seek to strengthen them. But the situation did not exactly develop in this manner.

"The main opposition I faced was from MEPs," Dr Borg explains.

Not that member states did not resist certain measures. Poland, for instance, is set to challenge a ban on the menthol cigarettes: the directive bans all "characterising flavours" in tobacco products in a bid to reduce their appeal to the young. And the requirement for text and pictorial health warnings to cover 75% of tobacco packs was reduced to 65% at their insistence: an acceptable compromise, in Dr Borg's view.

But there were MEPs who were seeking to reduce it further to 50%, and place the warnings at the bottom of the pack, rather than the top, which would greatly reduce their visibility in shop shelves, among other measures.

"The pressures of the tobacco industry were mainly felt by MEPs... governments were anti-tobacco, the Commission too," Dr Borg observes.

Mr Dalli had also been accused of holding a number of undeclared meetings with tobacco lobbyists:

However, his predecessor was accused of holding a number of undeclared meetings with tobacco lobbyists, and it was a manufacturer of snus - a form of oral tobacco native to Sweden - which claimed that an associate of his asked for bribes to repeal an EU ban on the product.

But Dr Borg states that he faced no pressure from tobacco industry lobbyists whatsoever, although he points out that they were probably aware of his intentions, and consequently saw no reason to attempt to persuade him to make changes to the directive.

He was, however, approached by representatives of the Swedish government which lobbied, unsuccessfully, in favour of repealing the snus ban.

Dr Borg also held meetings with anti-tobacco campaigners, stating that they have helped him get the directive through, particularly when MEPs presented amendments which could weaken it.

All these meetings, he is careful to add, were properly declared.

Defusing the GMO controversy

Another issue which Dr Borg strove to address - though his successor will be the one concluding the process - is the controversy surrounding the use of genetically-modified organisms (GMOs), which are ubiquitous in the Americas but far less widespread in Europe.

Products containing GMOs are not illegal in the EU, provided the GMOs used are authorised in the EU and the products are properly labelled. The most controversial issue is the cultivation of GMO crops: most EU countries - Malta included - are outright opposed to cultivating GMOs, but some - most notably Spain - have embraced them.

The pro-GMO minority means that the Council cannot muster a qualified majority to block the cultivation of a GMO crop that has been approved by the European Food Safety Authority.

As things stand, pro-GMO countries are wary of restrictive measures which may affect their agricultural sector, while anti-GMO states fear being forced to allow the cultivation of GMOs in their territory.

So Dr Borg sought to revive a proposal that had previously failed, but which appeared to have garnered increasing support by then.

Until now, whenever a GMO crop is approved for cultivation in the EU, member states are technically bound to allow its cultivation in their national territory. What is being proposed is to allow each member state to ban the cultivation of GMO crops, although they would not be able to prevent the importation of GMO-containing products.

MEPs appear to be supportive, and since the number of member states objecting to the proposal has dropped, Dr Borg is confident that an agreement will be reached by the end of the year.

"This should help defuse existing tension on the cultivation of GMOs," Dr Borg maintains.

Another controversy Dr Borg has had to deal with was the "Horsegate" scandal, in which meat products across Europe were being found to contain improperly declared meats, including horse meat which is considered a taboo food in countries such as the UK.

Dr Borg emphasises that the scandal presented no threat to public health, but notes that it has nevertheless received priority and tackled through measures including DNA testing and harsher fines, stating that this has led to a huge reduction in fraudulent labelling of foodstuffs.

EU Commissioner 'a small country's biggest advantage'

While Dr Borg emphasises that he was a European Commissioner, and not the representative of the Maltese government - and that he was ready to initiate proceedings against the Maltese government if deemed necessary - he notes that no Commissioner "forgets where they come from."

He observes that while Commissioners have specific portfolio, each law is discussed by the entire College of Commissioners, and that in these debates, Commissioners had the opportunity to bring forward their own country's perspective.

"I have not just been a Commissioner for Health and Food Safety full-stop; I was the European Commissioner responsible for these issues. But I took part in debates on every issue," Dr Borg notes.

This, he argues, was the greatest advantage of being a small country in the EU.

"At the Council there is a weighting of votes, although there is a veto on taxation, security and foreign policy. Six seats in the European Parliament is a proportionally high number, but it still represents six out of 751," he observes.

"But every other country only has one Commissioner: small countries' biggest strength is in the Commission."