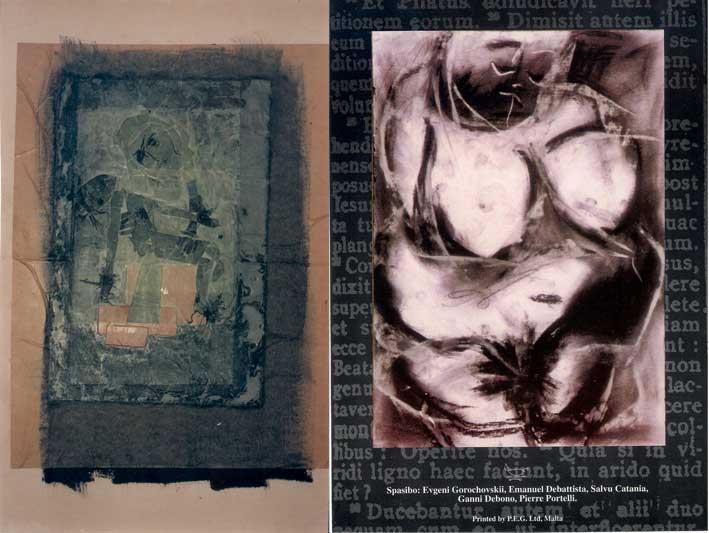

Years ago the curator and art critic who is no longer with us, Emanuel Fiorentino, had organized an intriguing exhibition of my works during the 1980s. These included a series of paintings and designs which portray scenes of the Passion of Christ and scenes which also manifest important aspects of Christianity, such as the birth of the Madonna, the Pietà and others. This exhibition had provoked a scandal as I rendered the Madonna in megalithic and prehistoric form. I exploited the form of the 'goddess of fertility' or, as she is more popularly known, 'the fat lady'.

In fact I recall with a certain cynicism and a smile (or even a laugh) that Emanuel had shown me anonymous letters which were sent by people who had seen the exhibition. They could not understand that I tried to unify the idea of our roots with the history and culture of our antiquity. On the other hand, it provoked a discussion on my placing of a megalithic Madonna together with stylized Byzantine-form Christ using minimalist and modernist lines.

Our culture is in fact rich because of these extremely beautiful historical cultural levels which are all different and even radically opposed, yet in an organic fashion they are integrated together in our culture. Malta has the intriguing ability to organize different cultures in a single bundle and this is what makes our culture strong. Unfortunately we ourselves are many a time unconscious of this.

If we are attentive, we may observe that our culture is not a pastiche of different cultures, but these different cultures found a way of integrating and consequently shaping a multi-ethnic culture within our own genetics. It is beneficial for us to be aware so that this genetic concoction would continue to be developed. My art was also reflecting these points. I was criticized not only by those who are scrupulous but also from those who always tried to portray themselves as avant-gardes.

The latter contingent could not understand how an artist like myself, who is far from being a religious person, could choose a religious theme as an artistic subject. The problem here is that these people forget that art as a sphere of activity is anchored in the culture which embraced each individual in their specific territorial and spiritual parameters. Christian values are not monopolized by a single and particular church.

Our history, also unified with that of Europe, is the history, whether one agrees or not, of Christianity. It is difficult and almost impossible to separate European history from that of Christianity. And if one bypasses this aspect, we will be making a drastic mistake in the analysis of history and even in that of our own development. We must understand that religious themes left in the hands of artists transcend religiosity. We have many examples such as the 'Vence Chapel' by Matisse, the 'Crucifix' and the 'Chapel of War and Peace' by Picasso, Rothko's marvel of spiritual metaphysical thought, Kandinsky, Malevich and many others who go beyond the particular religiosity of the church.

These are important thoughts which harmoniously form part of the new politics of the Mdina Biennale of which I am Artistic Director. The global response to this event has been phenomenal: Artists from Germany, Russia, England, the United States, Egypt, Chile, Italy, France, China, Australia, Poland, Iran, Iraq and many other countries immediately reacted to the event and proposed new work for the Mdina Biennale. The same goes for local artists. I discussed the Mdina Biennale with many artists to initiate artistic debate, because I do not believe that a Biennale is simply an opportunity to hang works and head off.

On the contrary, the Biennale itself is a work of art per se. It is an 'installation/performance art' in itself. This is how I will organise and exploit it. It is important that artists challenge and debate the chosen theme every time this event is held.

From this, it is already apparent that the spectrum of the Biennale has been significantly widened instead of being restricted to the idea of Christian Art. On the other hand I believe that this Biennale must establish a bridge with the past and thus the first theme for the Biennale is 'Christianity, Spirituality and the Other' where the idea of 'the Other' is to be interpreted in its most expansive sense. This includes faith, a lack of faith, atheism, theism, agnosticism, doubt, any form of spirituality or other. It means that we must create a visual debate on the relationship between man and spirituality in his existence and to see how this eternal theme will be interpreted by artists in the 21st century.

I was extremely pleased when I met with the Mdina Chapter to discuss my ideas and the conditions which should determine the Biennale's performance. My cardinal thesis is that the only criteria for the choice of works should be quality.

I am one who like Don Quichotte still believes, as reiterated by the English Poet Keats, that 'Beauty is Truth and Truth is Beauty'. Today this has an anachronistic resonance; however I am trying as much as possible to revive its position as one of the pediments of contemporary art. After almost two centuries of attacks against Beauty, maybe it is time to again begin to reflect.

Yet there is need to raise whole debates on the new role of modern and modernist aesthetics and to inject them with new and contemporary thought. Thus when vulgarity and sensationalism overshadow art, my logic concludes that works of such nature cannot be art. A piece can be artistic when art is predominant, and not vulgarity, sensationalism or any other non-art factor. Naturally there are works which provoke such a debate with strong effect. We can take as an example the eroticism manifest in Bernini's 'Saint Theresa', of Cafa's 'Saint Rose of Lima' and later in Rouault's incredible series 'Miserere'. Whenever art remains predominant no problems arise. The difficulty is when other non-artistic factors determine the work. This would be a grave mistake on the part of the artist.

In one of the many meetings held with Maltese artists on the Mdina Biennale, two artists expressed their difficulty in participating in a Christian/Catholic event and even found it strange that I took on my role within it. This incited a very interesting debate.

The first thing which I couldn't comprehend was how a contemporary artist is finding difficulty here when contemporary art accepts all and sundry as subject matter of art. It seems as if Christianity alone cannot be a subject of contemporary art according to these artists. A total paradox. Already for 100 years, the field of contemporary art has accepted that anything can be the subject matter of creativity.

And today, in a spectacular manner, the theme of religion is re-entering international contemporary art, after an important absence. Only, this theme is entering with a new characteristic, meaning the artist today has no religious-clerical duty to the creation of spiritual work. This aspect in fact imbues contemporary art with a highly exciting, intriguing and even transcendental atmosphere to spiritual art. In fact we have arrived at a new road which takes us back to the times when an artist today must "explore, criticize, celebrate, plead and subvert everything which confronts him" as rightly stated by Adrienne Dengerink Chaplin, a scholar and professor of art.

It would be a great mistake for one to interpret these works as ridiculous actions, as happened to the works of Chris Ofili in the Venice Biennale (2003) and also in his exhibition 'Sensation' at the Brooklyn Museum, New York (2001), so much so that he provoked an unprecedented anger in the Mayor of New York of the time, Rudy Giuliani.

Ofili's work was defended by Wilson Yates, an American theologian. Yates believes that traditional Christian symbols form an integral part of national cultures and supersede the strict and closed interpretation of any Church and particular religion. Symbols such as these are granted different forms of interpretation by believers and also non-Christians, as well as atheists, agnostics and those in doubt. In fact, Yates interestingly sustains that it is precisely this modern diversity of various interpretations of Christian symbols which is breathing new life into these traditions.

An interesting thing of today is that spiritual art and its religious forms are moving beyond traditional representation. Many are those artists who are developing the theme of religion to provoke questions on historical and intercontinental aspects. African art and that of Aboriginal Australia are classical examples in this sector. My example of the prehistoric Madonna reflects all of this.

Article edited and translated by Nikki Petroni