In my previous article, I discussed Al Athir's account on how, two years after Malta fell into Arab hands, a strong Byzantine army returned to conquer the island. After the devastation that the conquest of 868 provoked, the Arabs proceeded to fortify the main city of the island. Within two years, the new structure was strong enough to hold out against an invading Byzantine Army until a relief force arrived from North Africa which, in Al Athir's words, forced the Byzantines to flee.

Therefore, if one is going to uphold Al Athir's version and support the fact that Malta was not left deserted as affirmed by some of the Arabic chroniclers, the logical question would be: What happened to the island in the following decades? In my opinion, the answer is to be found in Al Athir's text.

Al Athir has more references to Malta in his historical narrative. However, some of them are not associated with Malta. During my undergraduate years at the University of Malta, I still remember Professor Godfrey Wettinger referring to one in particular but which according to Professor Wettinger, was not about the island of Malta but referred to a town in Sicily. Wettinger was following the main historical narrative, starting with Michele Amari and continuing till recently that this locality called "Malta" by Al Athir should not be confused with the island of Malta.

The main reason for this argument is the way Al Athir described this town Malta, without specifying that it is an island and also in the way he spelt the name. Malta is written without the "alif". In one particular instance, Malta is written in Arabic as [ملطة] and not [مالطة] as our island is normally written by Arab chroniclers both past and present. Thus, various ideas were formulated about this particular place. There were those who opined that this 'Malta' stands for the town of Mileto in Calabria. The idea that Malta stands for the name of a tribe was also suggested. It should also be noted that there is a town in Asia Minor, or modern-day Turkey and a village in Yemen, with this particular name.

According to the 19th century Arabic scholar Faris Al Shidyaq, Al Sihah mentions 'Maltiya' as being one of the Armenian lands which were part of the Ottoman kingdom. But even this cannot be the place referred to by Al Athir, as he contextualised his story with the Arabic conquest of Sicily.

At the same time, the possibility that this place is Malta and this is just a spelling variation resulting from a calligraphic error by Al Athir or another way the Arabs wrote Malta in the 13th century has not been explored. In Arabic, the variation lies only in a vowel. Malta is written here with the short vowel "a" instead of the normal long one, called Álif. Therefore, in Arabic, this can be read in various modes such as Malta (to be read in Maltese like habta, sabta, gabra) Malata, meleta, and in other pronunciations. It should be remembered that in Arabic, the short vowels are normally not written down. In the case of Malta, Al Athir did not write the short vowels and this accounts for the confusion that has arisen around the identification of this place.

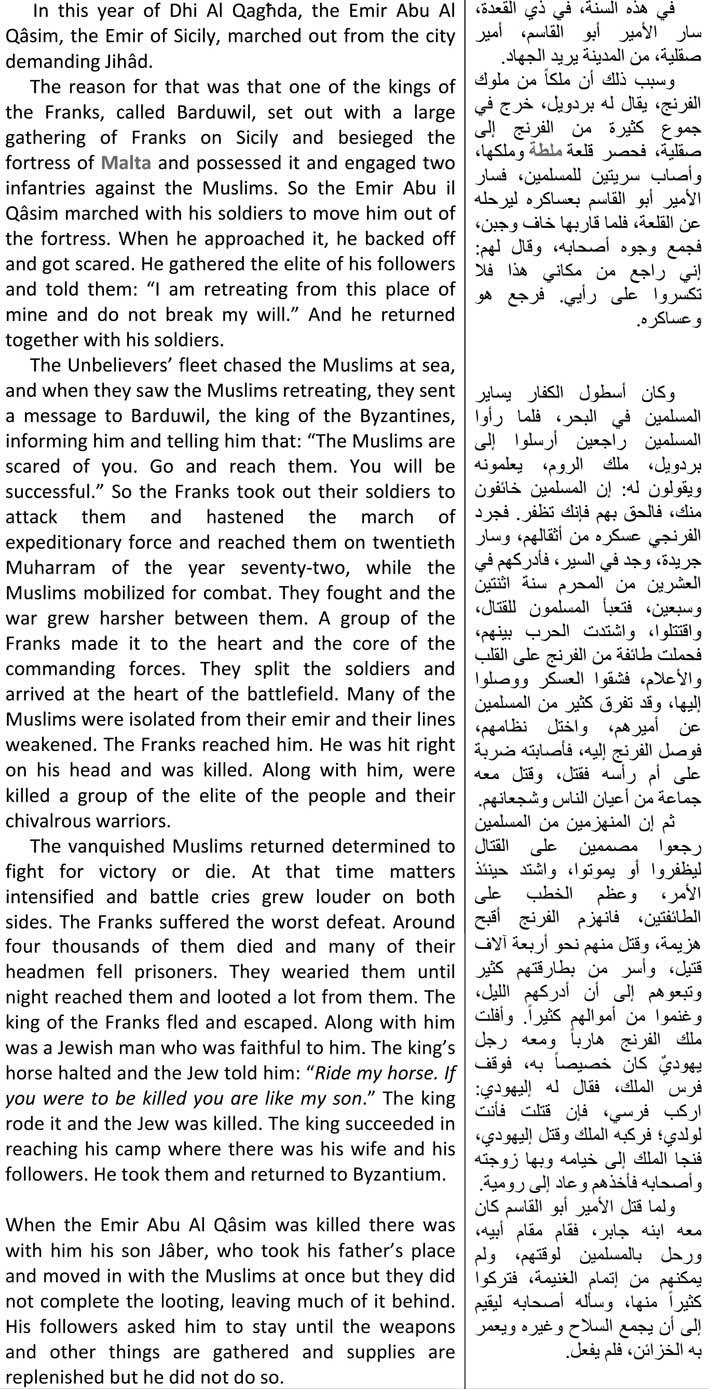

Al Athir mentions this place called Malta when he comes to discuss the killing of the Emir of Sicily, Abu Al Qâsim, which took place in AD 982. He was killed in battle following the loss of Malta to the Byzantines earlier on. Once again, I would like to thank Frans X. Cassar for providing a faithful, literal translation of Al Athir's text. The text of Al Athir is as follows:

This text is self-explanatory. The fort of Malta was part of a wider campaign that the Byzantines and the Franks waged together against Sicily from 891 to 892. The loss of Malta was followed by intensive battles on both sides at the end of which, the Emir of Sicily, Abu Al Qâsim was killed in battle. But according to Al Athir, the Arabs still succeeded in vanquishing the Franks and the Byzantine army returned to Constantinople.

It should be pointed out that Al Athir used the term Franks and Rum intermittently when referring to Christians, without making any distinction between the Christians of the West and those of the East or as they are normally defined between the Latin and the Byzantines. It was after Al Athir's time, that the term Franks started to be associated mostly with the Latin West and the nomenclature Rum with the Byzantines. Even if Arab scholars continued to use these terms intermittently up till the 18th century.

Al Athir described this Christian conquest as having been conducted by Barduwil or Baldwin whom he describes as one of the kings of the Franks. But before getting to the identity of Baldwin, one needs to remember the context of this text. Al Athir is writing at the time of the Christian crusades and the Arabs started using the name Baldwin or Barduwil randomly for any one of the rulers of the Franks, past or present. Such a name became infamous with the Arabs because Baldwin was a very common or popular Latin name with the Western Christians of this period. Furthermore, the first king of Jerusalem was Baldwin I who was a Frank. The popularity of Baldwin made a number of Arab scholars identify earlier Latin kings or generals, as well as Byzantine Emperors by this name.

There should be no doubt that Al Athir is not mixing the Baldwin of 982 with the other Baldwin of the time of the Crusades. This can be confirmed from an extensive reading of Al Athir as he refers to the Frankish king, Baldwin I of Jerusalem in another part of his chronicle where he describes the kinship of Baldwin I with King Roger II of Sicily.

On the other hand, it should be pointed out that the date in this Arab text is correct, as is that of the Emir of Sicily, Al Qasim. This correlates with what Alex Metcalfe states regarding the death of Emir Al Qasim in 982.

At this time, the king of the Franks was the Holy Roman Emperor Otto II. He was waging war in Southern Italy and this brought him in direct conflict with the Byzantines and the Fatimid Caliphate. At first, he was successful. He started the campaign in 980 and by the following year his armies had succeeded in reaching Southern Italy and were carrying out incursions on Arab Sicily. Therefore, this account by Al Athir falls exactly during the time when Otto II's armies were attacking Sicily and in that year, his forces had the upper hand. It was only in the following year, in 982, that Otto's forces suffered a heavy defeat and had to retreat to the north of Italy.

Otto had more than one general called Baldwin in his army and many of these Baldwins were Flemish. Al Athir seems to exclude that Baldwin was an admiral, even though Barduwil had to rely on a fleet to besiege the fortress of Malta. Admirals are known in Arabic as Emir il baħir.

The nearest Baldwin king one can find to 982 was Baldwin IV of Flanders. He was son of Arnulf II of Flanders (c.960-988) and Rozela of Ivrea (955-c1003) but was born in 980! Baldwin IV is recognized as having been a good warrior and is mostly remembered for his military campaigns in the Low Countries. However, due to his age, he cannot be the Baldwin to whom Al Athir refers in this text.

Al Athir adds another important detail. He defines Barduwil as the king of the Byzantines. While in this period, the Byzantine Empire was considered on a par with the Latin Emperor of the West, the Crusades had created the perception among Arabs that the Christian kings were one and the same family and the Byzantine Emperor was a vassal of the Latin Emperor. This is due to the fact that at the time of Al Athir, the Byzantine Emperors had lost much of their power after Constantinople was sacked by the Venetians in 1204 during the fourth crusade, with the result that the Byzantine Emperors started to appear as vassals to the Latin Emperor in the eyes of the Arabs. This explains why Al Athir defines the Byzantine Emperor as one of the Kings of the Franks.

In 982, the Byzantine Emperor was Basil II, who lived from 958 to 1025. Like Otto II, Basil too was engaged in a war against the Fatimid of Sicily. He had a formidable navy with which he succeeded in dominating both the Eastern and the Central Mediterranean. More importantly, in Greek, the name of the Emperor is Basileos, which one may rightly conclude to have been transliterated as Barduwil in Arabic.

According to Al Athir, the fleet of Basil II reached Sicily and conquered the fortress of Malta. Thus, the Arabs in Sicily found themselves besieged on two fronts. They were attacked by the forces of Otto II From the north, and from the East they were harassed by Basil II's fleet.

From a geopolitical point of view, it is very difficult to believe that in this warring scenario the island of Malta was left deserted, as was claimed by Himyari. With the Byzantines desperate to establish a base from where to launch their attacks on Sicily, they would have marched and occupied a deserted island with formidable harbours. Malta's good harbours would have served the Byzantine navy well. As a historian, it is very difficult for me to accept that between 870 and 1054, which are the two dates during which we know that Malta was attacked by the Byzantines, no other attacks took place. It is even more difficult to believe that Malta was left deserted and was not occupied and used as a base by the formidable Byzantine navy during the seaborne campaigns of 982.

Therefore, if Al Athir's 'Malta' or [ملطة] stands for our island, this proves that the Fatimids created and fortified Mdina and the island was never deserted or better still unpopulated. The Arab city had gone through a siege in 982. This time, the return of the Byzantine army was successful and gave them control of the island.

But the main reason why Al Althir's "Malta" is not considered to be the island of Malta is not in the spelling but more in the way that Al Athir described the action leading to the fall of the fort, when he wrote that "one of the kings of the Franks called Barduwil, went out with a large gathering of Franks on Sicily and besieged the fortress of Malta". As Al Athir did not specify the geographical position of Malta, this fortress is normally taken to be in mainland Sicily. However, a study of the medieval Arab texts yields no reference to a town in Sicily by the name of Malta or ملطة. Each time that a medieval Arab chronicler spoke about Malta, he always referred to our island as [مالطة]. Indirectly, Al Athir hinted that the fortress of Malta was not in Sicily as he recounted how the Arabs had to engage their fleet for its recovery but due to the intervention of the Byzantine navy, the mission proved a failure.

Secondly, it was normal among Arab chroniclers to discuss Malta together with Sicily and they never questioned that the place being described is our island. A case in point is Al Maqrizi, who wrote about the siege of Malta in 1429 and linked it with an attack on the island of Sicily. This passage is going to be a subject of a separate study, which will appear soon in a book about the Great Siege, which is being edited by Maroma Camilleri. It would be extremely strange and verging on the incredible that in Sicily there was a very important town called Malta, which was subject to a siege and the nomenclature [ملطة] is only mentioned once in the Arabic narratives of the Middle Ages, that is, in this particular story.

The third indication that this fort was in Malta is to be found in the historical narrative itself. The fortress of Malta fell before 1st Dhi Al Qagħda of AH 372, which corresponds to Tuesday 17th April 982. On that date, Abu Al Qâsim called a jihad for its recovery. Most probably, the fort of Malta was conquered in the previous summer and it took over a year for the Emir, Abu Al Qâsim to declare a jihad to regain it. According to Al Athir, Al Qâsim declared war on the 1st Dhu Al Qagħda of AH 372, that is, at the start of the sailing season. The main campaign was fought in Sicily on 1st Muharram AH 372 or 26th June 982, during which, Abu Al Qâsim was killed. The fact that the Emir had to wait for winter to pass before starting the campaign indicates that he had to engage his fleet to wage war. In simple words, the fortress was an island in Sicilian waters. It should be remembered that in winter the fleet was rarely engaged in battle. The navigation season in the central Mediterranean started in April and ended towards the end of October. If Malta was in Sicily, as has been claimed, then Abu Al Qâsim did not have to wait for winter to pass before launching his attack.

Fourth. The Byzantines had the time to replenish their fort with troops, as they sent two armies of foot soldiers to oppose the landing of Abu Al Qâsim's forces.

Fifth. It should be pointed out that Al Athir uses the verb ملكها (malakaha), which literally means that the Byzantines have possessed the fortress of Malta. Thus, by using such a verb he is implying that it was a permanent takeover.

Sixth. Al Athir avoids discussing what happened to Malta and at no point, does he speak about its re-conquest by the Arabs. His text shows that this fortress was held in high esteem by the Arabs in Sicily. The proper reading of this text would be that Malta was attacked together with Sicily in a coordinated attacked made by the Byzantines and the Franks on the Fatimid of Sicily. The Arab forces tried to regain Malta but as already stated, they were repelled by the Byzantine fleet. The Byzantine army followed the Arabs to mainland Sicily, where they were joined by the armies of Otto II and a big battle was fought during which Al Qâsim was killed but the Arabs still were victorious. This explains Al Athir's euphoric description of the Arab victory over the Franks and the Byzantine forces without referring to Malta's destiny, as this would have demeaned his narrative. In fact, it is known that Otto II had to withdraw his armies from Sicily. Instead, Al Athir says that Al Qâsim's son, Jâber, did not want to continue fighting, which means that the Arabs lifted their siege and did not cross the channel and fight the Byzantines who were occupying the fort of Malta.

With the help of Frans X. Cassar, who is patiently researching medieval Muslim accounts for references about Malta, I will be presenting more Arabic texts that can help us know better what really happened in the dark years of the 10th and 11th centuries.