This year children will be enjoying the excitement of carnival, dressing up, attending parties and watching the floats and companies parade by. But, a little less than 200 years ago, a tragedy took place which should never have happened. And, it would seem, all because someone left a door open.

In 1823 Malta was gripped by famine and while carnival revelry was very much welcomed as a diversion from such misery, the then customary traditional donation of bread to certain groups of children would have been all the more welcome.

Young boys from Valletta and the three cities were in the habit of joining in the last few days of the carnival celebrations. As the processions ended they went to Mass, in Floriana, after which they all went to the Minori Osservanti convent, where they were each to be given some bread and fruit.

This was organised by the Church's catechism teachers with the idea of keeping such young, impressionable boys away from the worst excesses of the carnival celebrations.

When the event took place on February 10, all went well. But the following evening, the Mass in Floriana lasted an hour longer than it should have done. This meant the children's procession arrived in Valletta just as the celebrations in the city were ending and people were beginning to return to their homes.

To receive their bread, the boys went through the vestry door into the convent and down a corridor to leave through another door, in St Ursula Street, where they received their alms. Once everyone was inside the vestry door was shut, to prevent any boys from going back in for another handout.

However, on this occasion the door was left open and seizing the chance to receive some bread themselves, other children and some adults went in unnoticed among the 100 and more o boys entitled to be there. Only then was the vestry door locked.

An account of what followed, written in a private letter, was actually printed by a certain Hezekiah Niles, an American editor and publisher of a national weekly news magazine, the Niles' Weekly Register and the Weekly Register, based in Baltimore, USA.

There is nothing to say who sent the letter, or why details of such an incident should have been printed in an American publication. But the writer described the 'melancholy incident of a most affecting catastrophe' and included very precise details such as that funds given partly by the government and partly by benefactors paid for the bread and fruit distributed to the boys; and that the only lamp in the corridor was unfortunately extinguished, possibly by boys playing around and throwing their caps at it. In the darkness those in front could not make out the eight dangerous steps ahead of them, which lead to the half closed door at the opposite end of the corridor. The moment the boys reached the steps, they quickly fell, landing on top of each other. With so many still pushing forward, prostrate bodies instantly blocked the doorway. Some were even found in an upright position against the partition and not only was the area levelled but the bodies were forced two feet above it.

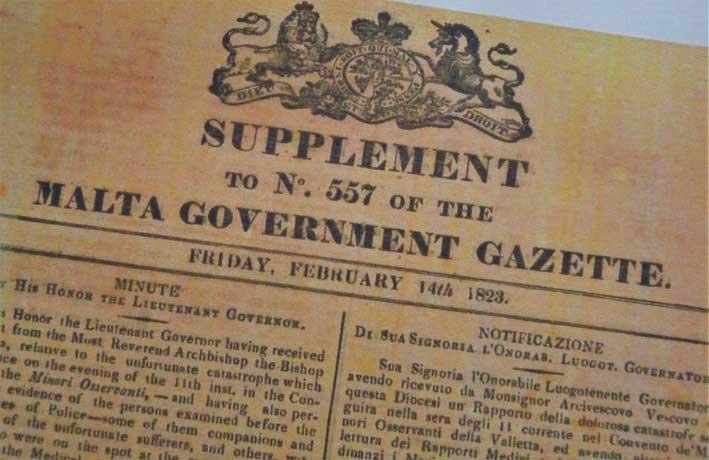

Minutes taken by the Lieutenant Governor of Malta, three days later recorded that the children's screams were quickly heard by those distributing the bread and by neighbours who tried immediately to help. After trying unsuccessfully to get the boys out through the door, which opened inwards, Some people ran to get the vestry door key from the church, and went in. But those who entered from the vestry, passing through the crowd to break down the door at the bottom of the steps; were too late to save many youngsters. However, the boys who had merely fainted soon came round and some who were carried out, apparently lifeless did recover. But 110 boys, aged eight to 15 were killed, either from suffocation or by being trampled on. It was left to the Royal Malta Fencibles, some of whom were bases at St Elmo, to help deal with the final aftermath of the disaster.

The lieutenant governor was convinced only persons with the most depraved or perverted minds could ever think that there was the smallest wilful or intentional fault of anyone's to cause such a tragedy. However, it was evident that there were such individuals on the island as reports, of a malignant nature were raised, and circulated.

He stated it would be the government's first duty to study the reports if there was any truth in the rumours the perpetrators would get the punishment they deserve. A few days later the investigation concluded that the stampede was the result of a succession of errors and no entity was responsible for or accused of the children's deaths.