I remember how embarrassed I used to be as a young engineering design student in Germany in Saarbrucken and later on in Wuppertal, when asked to give public presentations. I had never been asked to do so in Malta, let alone trained in them. This is what pushed me to organise science and technology initiatives for my students later on when I was directly involved in education initially at De la Salle College.

I was later hooked by Professor Stephen Hawking's books, A Brief History of Time, Black Holes and Baby Universes, The Universe in a Nutshell, and his biographies which I read and reread. His books have never really left my bedside.

Along the years, Hawking made me realise two important facts of life that I was sure would be beneficial to students in their quest for learning and knowledge. Firstly, it was his strength of mind, his freedom of thought that ALS could not conquer and kill. It actually made him thrive and work hard despite great physical limitations. Secondly, his continued study of the stars and the universe and at the same time the humility that man must have. Indeed Hawking loves Newton's letter to Robert Hooke in which Newton declares that standing on the shoulders of giants helped him to see further than he could all alone. Newton with all his discoveries considered himself to be just a little boy finding a smoother rounder pebble or prettier shell when the immensity of the ocean of truth was still to be discovered.

I realised that the determination and great achievements in Astrophysics of this wheel-chair bound theoretical physicist despite his physical drawbacks with motor-neurone disease, must be used to inspire students to be strong in their quest for learning and knowledge. I wished to come up with some pedagogical means to kickstart abilities and skills that lay dormant in students unaware of their latent abilities. My wish was to create a platform for students where their imagination could be let loose and fired into something that could last a lifetime. Schools were becoming more sophisticated, labs were being more accessible. There was therefore the infrastructure more or less available. The more I saw the picture of Hawking in his wheelchair on the A Brief History of Time, the more I asked myself why not give it a go.

I was at De la Salle College where I taught Physics and Graphical Communications when I put into action a plan to actually make up this platform of activities for students, where they could learn new skills or sharpen the ones they already had. It was simply an effort not to miss. My idea appealed to Brother Thomas and Brother Dominic, and Brother James confined in his library never stopped talking about it. My students were incredibly enthusiastic and produced not just detailed technical drawings and plans, but also the 3-D projects - actual homemade ACs units - actual fully functional petrol fuelled rockets, homemade go-carts welded by a 14-year-old... The fun, the passion, the creativity, the doing skills, (and headaches and danger!) were uncontainable!

I eventually brought the idea to San Andrea Senior School where we still organise the activity every year. Groups of students are asked to present viva voce researched investigations of their choice. Seminars are held, supervised by science teachers, and participants are grilled by peers and teachers alike. Finally, a winning team is selected by a panel of experts following a public presentation.

When the project was presented at San Andrea Senior School, the Headmaster at the time, Evan Debrincat, was thankfully a very technical, practical man and thrilled at my idea. He kept asking about the methods I had used at De la Salle. I decided to call the project after Stephen Hawking hoping that students would emulate his tenacity and skills. At the time, I was HOD of Science and Technology, and chairman of the Technology Focus Group meeting at the University, and immediately thought of meeting Professor Hawking himself. I left no stone unturned to get through to him at Cambridge University and I remember how excited I was when he not only asked to meet me but also very generously invited me as a teacher of physics to send him any question I had about the universe! Understandably, my joy was boundless. Professor Hawking wanted a question about the universe so that he could prepare an answer for me when we met, which of course I did! I was more than aware that if I had read all the books he had written, it did not mean that I had actually understood and owned all that he had written! Far from it!

It was with trepidation and anxiety that I drove some San Andrea students and staff in pouring rain at night from London to Cambridge. The climax of my mission was meeting this wheelchair-bound physics colossus, and although he had asked me to send my universe query, I was now not so sure that my question had after all been smart enough, or perhaps easy enough for myself to already know the answer! The silence in the car, the black holes dancing in front of me, the snoring of the girls, the vibration of huge wheels of heavy vehicles I overtook, the wrong junctions I took, the junctions missed, the mad wipers slashing frantically across the windscreen, the speedometer moving up or down in direct proportion to the flow of my racing thoughts... and I kept asking the question, I kept counting the hours before our meeting.

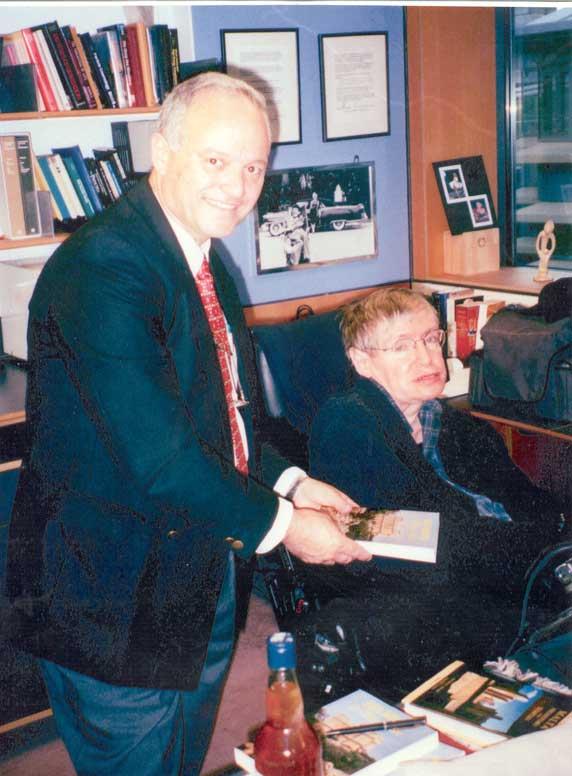

We met at the DAMTP in Cambridge. We reached the University hours before the appointed time. I did not want to risk anything at all. Better to wait safely and patiently than wait in traffic jams. We had the opportunity to have a lovely meal in the university canteen as we waited to be called and eventually we were escorted to his office. It was so beautiful discussing physics with him and the Ph.D. students in his office. I still remember them jotting down formulae and drawings on the board. His monotonic voice still rings loud and clear as our eyes met, and his explanation to my question on the expanding universe appearing incredibly fast on the monitor during the brief discussion. I still cherish with great pride and gratitude those unforgettable moments when he expressed his sincere happiness and joy as I told him all about our school San Andrea, and the need to have his name on our science endeavours! To this day, we still call it the Stephen Hawking Science and Technology Project.

I remember the cup of tea he drank and the way he drank it. I remember how silent the three students were, bewitched, literally mesmerised by his presence the three students. I myself was in awe of the person who dared defy Hoyle and said that black holes are after all not truly completely black holes! I still remember his cold, immobile hand as I grasped it almost with reverence while placing in front of him a humble bottle of pure honey from the Mġarr garigues and a copy of my book Selmun A Story of Love.

But mostly I remember the captivating smile on his face, the understanding twinkle and kind brightness in his talking eyes as he spelt on his monitor, "I am so glad to be of service to science in Malta..."

The quest for discovery is inherent in human nature: a toddler explores the little room, the explorer ventures into strange, untrodden jungles; someday the spaceship will leap into intergalactic space. Man is always in 'quest of' land, new horizons, and new knowledge: the quest for discovery rattles humanity's curiosity and creativity. Man has no respite, will never have. Man is not man without this quest. "If we reached the end of the line, the human spirit will shrivel and die," Stephen Hawking wrote somewhere in his The Universe in a Nutshell.

And he has done simply that: he has never given up, going on with extraordinary intelligence, wit, humour, charisma, singular stubbornness always seeking a delusive theory that would seal everything. That has kept him going and going, probably keeping him alive despite the short life prognosis he was given in his early twenties when he was diagnosed with ALS, making brilliant discoveries in the process.

His birthday on 8 January , 1942, as strange coincidence would have it, was the 300th anniversary of Galileo's death, coinciding almost to the day with Isaac Newton's own birthday. Stephen however considered this as simply another coincidence as probably as many as 200,000 other babies were born with him on that day. He even occupied the same Chair as Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at Cambridge once held by Isaac Newton. Time, as fate always come round: he died on 14 March, 2018 the same day when Einstein was born in 1879.

His father Frank, a specialist in tropical medicine, and his mother Isobel had been to Oxford as students. He was a smart boy at St Albans, skinny and puny, uniform always in a mess, speaking fast and confused; his peers called his speech "Hawkingese". He seemed to have been fun in class, witty, sometimes bullied as well as respected. His writing was untidy, his work shoddy and careless, never tied to his studies, brilliant at Mathematics. Aged 17 he went to Oxford getting a first-class degree that was the entry ticket to his research career in Cambridge. As an undergraduate he is remembered as laid-back, fun loving, athletic, enjoying life.

Gradually, ALS took over his body and confined him to a wheelchair. At 21, in 1963, he married Jane Wilde, a student friend and they had three children. The wheelchair did not shut him away from life: he loved life, he wanted to live life under his own terms, and he did. He spoke through a computer, his body was not free, but he even danced in his wheelchair and teasingly drove the wheelchair over students' toes. It is said he sometimes drove his wheelchair over the toes of people he did not like, like Prince Charles, and regretting not having the opportunity to run over Margaret Thatcher's toe!"

I cannot move, I cannot speak, but my mind is free! He eventually became the most famous theoretical physicist forwarding the unexpected link between the universe and quantum dynamics. Despite the fact that he never received a Nobel Prize for his theories as they were never verified by experiment, he received the more valuable Milner Prize worth millions of pounds.

Some of his achievements

The existence of Black Holes were first predicted by Einstein and Oppenheimer of atomic bomb fame who worked on this idea, suggesting that stars would collapse under their own gravity to a singularity with so massive a gravity that not even light can escape them. Hawking changed this attitude: black holes are not just sucking destructively, with Roger Penrose he theorised that an exploding singularity was what created the universe. That is, crushing everything into an infinitesimally small singularity, is the reverse of the creation theory of the Big Bang when everything is exploded out of singularity. He also went on to theorise on matter and anti matter, leading him to propose the radiation from the edge, called the Hawking Radiation that must come from a black hole. He wanted to find what is now called the theory of everything, a simple, elegant formula, or structure, or framework that would explain everything, most of all his astonishing theory that linked the large cosmos and gravity to the infinitesimally small sub-atomic particles.

Hawking was the person who explained how a huge explosion from a black hole's singularity collapse some 15 billion years ago, was the starting point of our universe, a singularity exploding into matter and energy that clumped together to form us, life, planets, solar systems, stars, galaxies...

On God

Stephen Hawking was the scientist whose lasting gift to mankind is his linking the great theories of pioneers such as Newton and Einstein. He did actually conclude that God does not exist. "I believe the simplest explanation is, there is no God. No one created the universe and no one directs our fate. This leads me to a profound realization that there probably is no heaven and no afterlife either. We have this one life to appreciate the grand design of the universe and for that, I am extremely grateful."

His words unleashed great discussions and great debates that had never really abated since the great arguments in the middle of the 19th century between divine creationism, and Darwin's budding science of evolution. The Genesis creation and flood narratives were then questioned and the situation has never been really ironed out, so that Stephen Hawking's assertion that he had come to the conclusion that "there is no God", which raised many an eyebrow. But he appears to be calm embracing this view, and confident in this, indeed succumbing to the fact that it is enough during the one life we have, to lie back and appreciate this grand design of the universe. Incidentally, this somehow happens to remind of the predicament of a humble local priest, a great and brilliant poet, Dun Karm Psaila and what he says in "Il-Jien u lil hinn minnu" when he himself questions the existence of God. The poet simply decides to stop worrying, his faith is enough, his belief is enough, hearing the heart beat of his mother as a baby is enough, love should see him through. Only Stephen Hawking would not let go silently, he was grateful for a fruitful life more than anyone else was.

In realty the debate is still on, it has always been and as long as man believes and as long as there is faith it will keep going on and on, because no one and nothing is going to take away anxiety, curiosity, imagination, fear, love, hate, gratefulness, self-awareness, analysis, synthesis and other attributes from mankind which raise humanity that enormous step above other animals. After all, as Hawking himself once said, we are just an advanced breed of monkeys on a minor planet of an average star; only we can understand the universe, and that is something monkeys cannot do. And that makes us so special.

He was aware that he had to keep looking at the stars but at the same time looking at his feet and being curious in the process, and asking questions - probably the same questions he asked himself when as a little boy his mother would make him lie down looking at the night sky in silence, just asking himself questions. And wondering about the stars.

Stephen Hawking's ashes will be interred next to the remains of Isaac Newton, J.J. Thompson, Ernest Rutherford and 17 British monarchs in Westminster Abbey.