The Great Siege of 1565, where the Knights of St. John and the Maltese beat off an invading army of Ottoman soldiers, as chronicled in The Malta Independent on Sunday on 2 September, is one of the two military victories that Malta commemorates on ‘Victory Day’ on 8 September. The second victory, much like that of 1565, was part of a conflict that could have potentially changed the very make-up of Europe.

World War Two was a world-defining conflict, and Malta found itself right in the thick of it. With France invaded and Great Britain on the ropes, Benito Mussolini interpreted events as clear enough evidence that victory for Adolf Hitler’s Germany was only a matter of time. Hoping to be able to get a good deal when the Allies eventually surrendered, Mussolini’s Italy entered the war on Hitler’s side on 10 June 1940. Malta became Il Duce’s first target.

The ensuing two years saw Malta became the most bombed place on the planet to date and saw the Maltese people endure near starvation. The Italians flew just over 35,000 sorties over Malta; whilst the German Luftwaffe flew over 30,000 sorties themselves in 1942, when the blitz truly intensified, alone. In fact by mid-1942, the average Maltese worker was consuming just 1,500 calories a day. By comparison, the consumption of an average worker in Britain never went under the 2,800 calorie mark at any point during the war. One could live with such a calorie intake; but it would lead to rapid weight loss and fatigue.

Above: Italy’s surrender was announced on 8 September, Top – King George VI salutes Malta in 1943 (Royal Collection Trust)

Food wasn't the only thing running out. Medicine was also in extremely low supply; to the point that when Royal Air Force pilots fell sick, they were given a choice of medicine from either a blue, green, or brown bottle - all of which were filled with water as opposed to medicine (in psychology this is called the Placebo Effect). Fuel supplies were also dwindling, and the island’s new Air Commander Air Vice-Marshal Keith Park warned in midst of the 1942 blitz that there was only a few weeks supply left.

The loss of Malta could well have resulted in the entire loss of the North African front. Over there the British, led by Lieutenant-General Bernard Montgomery, were engaged in a long to-and-fro conflict with the German Afrika Korps, led by The Desert Fox Erwin Rommel, and it was key that Malta was reinforced so that it could continue to carry out naval attacks on German supply convoys to the front as it had being doing so in the second half of 1941 when allied attacks sank 60% of Axis supply ships going to North Africa, meaning that a large-scale British counter-attack, Operation Crusader, was a resounding success. With the intense bombing campaign against Malta in 1942 however, the supply lines were once again open. Britain saw the desperate need for a resupply effort, and as a result a huge convoy was put together. This convoy became known as Operation Pedestal, and it was to be a turning point for the war effort in Malta.

The massive map used to plan the invasion of Sicily at the Lascaris War Rooms

The convoy sustained heavy losses, with nine of the fourteen merchant ships sunk along with several destroyers, cruisers and the aircraft carrier HMS Eagle. However, the supplies that did arrive in Malta between 13 and 15 August were key to turning the tide of the war, and as a result the operation as considered a success.

Admiral Eberhard Weichold, who headed the German naval attaché in Rome, summed up the impact of Operation Pedestal on the dynamics of the North African front; “To the continental observer, the British losses seemed to represent a big victory for the Axis, but in reality the facts were quite different, since it had not been possible to prevent a British force, among which were five merchant vessels, from reaching Valetta [...] Thanks to these new supplies Malta was now capable of fighting for several weeks, or, at a pinch, for several months. The main issue, the danger of air attack on the supply route to North Africa, remained. To achieve this objective no price was too high, and from this point of view the British operation, in spite of all the losses, was not a defeat, but a strategical failure of the first order by the Axis, the repercussions of which will one day be felt.”

Landing craft gather at Grand Harbour as preparations for the invasion of Sicily intensify

In fact, in August – the same month the convoy arrived in Malta – 35% of all Axis shipping to North Africa was lost. Historian Tony Spooner writes that the following month, Rommel’s forces received only 24% of the 50,000 tons of supplies needed monthly to continue offensive operations. The supplies that did arrive had to be landed in Tripoli, which was many miles behind the battlefront. The lack of food and water started to take its toll; Spooner writes that there was a sickness rate of 10% amongst Axis soldiers as a result of the lack of supplies. Similar success was registered in October; two fuel-carrying ships were sunk, and another lost its cargo despite the crew managing to salvage the ship, meaning that the Germans were desperately low on fuel – which was much needed for its tanks. Knowing this, the British launched an offensive on 23 October in what became known as the Second Battle of El Alamein. Meanwhile, an air-submarine raid launched from Malta sank what was effectively the last effort at re-supplying Rommel at El Alamein. The three fuel tankers in the convoy were sunk at the cost of seven British bombers and fighter-bombers. Montgomery’s commonwealth forces succeeded at El Alamein, and the tables had truly turned on Rommel and the Afrika Korps.

With victory at El Alamein, and Operation Torch landing in Morocco in November 1942, Allied forces closed in on full control of the North African front. This couldn’t have been done without the work of the RAF and Royal Navy forces stationed on Malta. The naval base at Manoel Island was known as HMS Talbot (even naval land bases were named as if they were ships – Fort St. Angelo for instance was known as HMS Egmont), and the base supplied 1,790 torpedoes to British submarines. Spooner estimates that these submarines alone sunk around 650,000 tonnes of Axis shipping, with another 400,000 tonnes damaged.

The naval base at Manoel Island, known as HMS Talbot

Such was the effect of the naval efforts out of Malta that the Chief of Staff of the Afrika Korps Fritz Bayerlein once claimed; “We should have taken Alexandria and reached the Suez Canal had it not been for the work of your submarines”.

Convoys, such as Operation Stonehenge and Operation Portcullis, were now arriving in Malta without losses, so much so that supply ships began to be sent without escort. The island was truly on the offensive as 1943 dawned and with victory looming on the African front, all eyes turned to Italy.

The Axis surrendered in North Africa on 13 May 1943, and in the same months operations had begun in preparation for Operation Husky; the invasion of Sicily. Islands like Pantelleria and Linosa were neutralised, whilst bombings on Sicilian airfields increased into July. In the same month, American General Dwight Eisenhower, Admiral Andrew Cunningham, the now General Bernard Montgomery, and RAF Air Marshal Arthur Tedder occupied the Lascaris War Rooms in Valletta. The underground chambers were used as an advanced headquarters for the impending invasion.

British tanks charge through a gap in a minefield during the Second Battle of El Alamein

The planning was exhaustive and brought together British, French, Canadian and American forces which sailed from various places such as Malta, Tunisia and even the United Kingdom itself. Air support also came from Malta, but bombings on Greece from the Middle East were also used to make it seem like an invasion was to take place there instead. In fact, the preparation for Operation Husky involved one of the most perfectly executed acts of deception in the whole war; Operation Mincemeat. A corpse was disguised as a British Royal Marine Officer and deposited it into the sea with a briefcase full of fake invasion plans. The idea was that the corpse, which was actually that of Glyndwr Michael – a Welsh homeless man who had died after eating rat poison, would drift into Spain and that the fake plans, which indicated that Operation Husky was actually an invasion of Greece and not Sicily, would be passed onto the Germans by Spain’s General Franco, who despite being neutral in the conflict somewhat sympathised with Hitler’s cause.

Historian F. H. Hinsley later wrote that the deception was a resounding success and that the Germans had moved a substantial part of their forces from Sicily to Greece, until the invasion of Pantelleria later diverted their attention back to the western Mediterranean. Still, when the real Operation Husky was launched against Sicily on the night of 9 July 1943, the island was liberated more quickly than anticipated and losses were lower than predicted. By the end of July in fact, it was clear that the only option for the Axis forces was evacuation through Messina to mainland Italy and the continuing of the fight there.

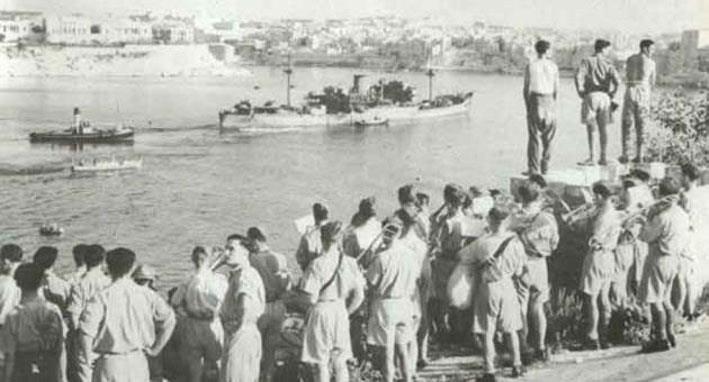

A ship forming part of Operation Pedestal arrives in Grand Harbour amid celebrations

Unrest was rife within the fascist Italian regime meanwhile, and Mussolini had been dismissed as Prime Minister and spirited off to the island of Ponza under arrest. He was replaced by Pietro Badoglio, who begun to try find ways to seek peace terms with the Allies. Indeed, an agreement was reached in early September, and the Armistice of Cassibile was signed. By this armistice, Italy was to defect to the Allies, and all naval ships were to make their way from port to Malta.

The surrender of Italy was officially announced on Allied radio on 8 September. Incidentally, on that same day in Senglea, the statue of Mary, known as Il-Bambina, had been taken back to its home locality from Birkirkara – where it had been held for safe-keeping since January 1941 – for the city’s feast. As the procession reached the still devastated wharf, shortly after leaving St Philip’s church, destroyers in Dockyard Creek aimed their searchlights onto the statue of Il-Bambina, while a loudspeaker from one of the ships broadcasted the news of the Italian surrender across the port.

The tears of joy on the faces of all those present symbolised that as of 8 September 1943, the war for Malta truly was over.

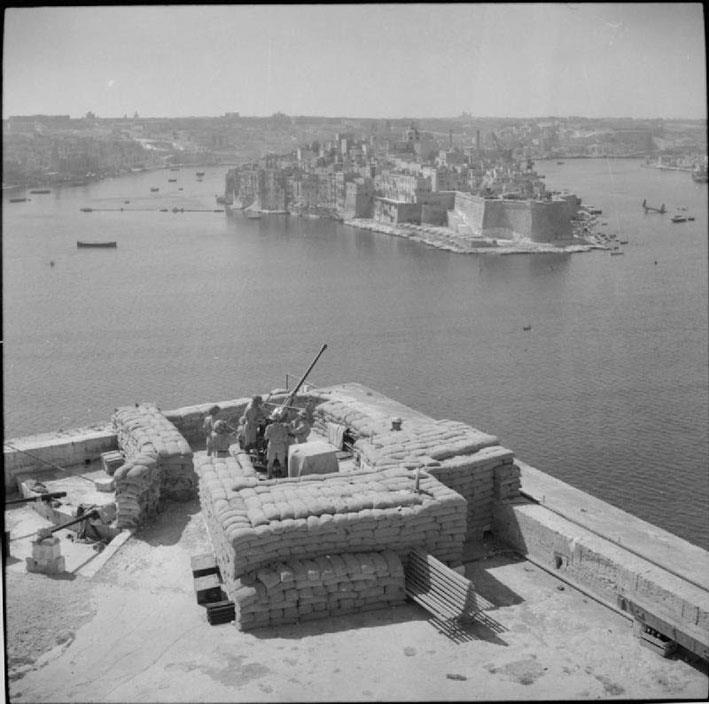

Soldiers, possibly from the Royal Malta Artillery, man an anti-aircraft post over Grand Harbour