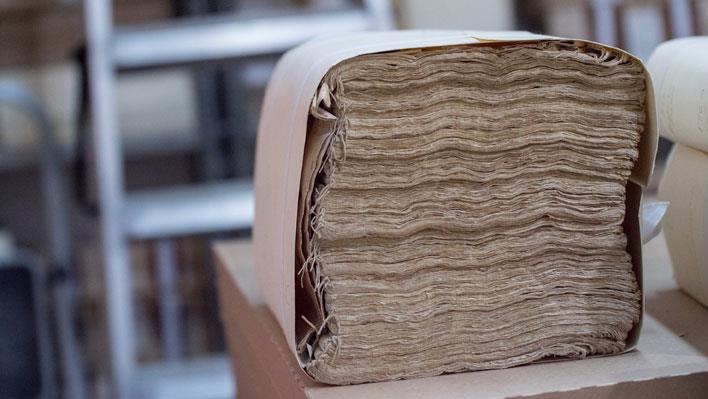

Although currently surrounded by scaffolding, on entering the Notarial Archives in St Christopher Street, Valletta, one senses the huge amount of history of both the building itself and its contents. Numerous boxes scattered around the building, The Notarial Archives Foundation is currently working on what is estimated to be two kilometres of documents to rid them of infestation by bookworms.

Dating back to the Order of the Knights of St John, the archives are bursting with notarial records, which shed light on numerous aspects of Maltese life and customs that have been forgotten over the passage of time.

The Malta Independent on Sunday met Dr Joan Abela, the consultant historian for the Notarial Archives ERDF Rehabilitation Project, and Vanessa Buhagiar, administrator of the Adopt a Notary Scheme and a student who is currently reading for an MA in Mediterranean Studies at the University of Malta and writing her dissertation on 18th century merchants in the Mediterranean. Both display joy and passion when talking about the archives and the hidden treasures found within the ancient bindings. Dr Abela explains that currently the oldest document found within the archives dates back to 1431. The document itself gives an insight into an Arabic tradition ‘zardah’ (the charitable distribution of food to the poor after a religious service) in Gozo. Dr Abela stresses the fact that this document, which was found by chance, is older than the discovery of America, thanks to Columbus, 60 years later.

PHOTOS: Alenka Falzon

Volumes full of human tragedy and the sale of human beings

The log book of one of the corsairs contains a variety of information regarding a specific expedition, from the licensing of the pilot, to the cargo which the ship would be carrying – from livestock to living human beings. A successful voyage for corsairs usually meant that slaves were captured.

Vanessa points out that in his log book, Corsair Bendetto Valentino refers to a particular record of the sale of slaves, containing their names, age, nationality and who eventually became their owners. The archives are full of contracts with the sales of human beings, priests, mothers and children. She points out that the highest price for a slave was 799 scudi for ‘Irhuma Figlio di Mishud d’anni 20 di Gerba’, suggesting that he was literate or trained in a particular craft, so therefore was a good investment. Around the 17th century a law was promulgated which banned slaves from amputating parts of their body, reflecting that slaves would rather inflict pain upon themselves than be consigned to row on galleys.

Nerous contracts reveal how so many people underwent forced voyages in inhuman conditions throughout history, and it is still happening today. Dr Abela reflects that the documents repeat the same story: how man’s greed is the cause of inhumanity throughout history, and how truly nothing has changed. Today, many people are still oblivious to the issue of migration in the Mediterranean, which has been going on for centuries.

One voyage told by two different letters

Apart from log books and legal papers, the archives also house intimate letters which shed light on different types of relationships, and what went on among ordinary people. Vanessa produces an account by Pietro Stellini, a wealthy corsair whose ship capsized in a storm and most of his crew were drowned. Stellini, who ended up on the shores of Tripoli and a slave, sent two letters – one to his mother and another to his wife, informing them of his situation. The letters ended up in the Notarial Archives as they were used as evidence in a court case between the mother and wife.

The letter to his mother gave a full account of the capsizing of the ship and the loss of life. He reassured his mother that he would be all right because the Madonna appeared to him to guarantee his safety. Buhagiar reads the last line in Latin and translates it as ‘don’t be sad for me as I prefer to be a slave rather than dead like the rest of my crew.’

Whilst sorting through other documents in the archives regarding the Inquisition in Mdina, the team had come across Stellini’s release papers, and also that he was brought in front of The Inquisitor due to blasphemy. Dr Abela finds it blasphemous that such documents were just dumped, with no awareness of their historical importance.

From an abandoned archive to the Mother of all Archives

The archives reflect an uninterrupted history from the mediaeval period all the way to the present day. The Archives give a broad view of the evolution of Maltese society, not just with regard to the law but also including handwriting, paper and different forms of binding and use of parchment.

There is a need to create more awareness to improve conservation methods and research in the archives and the Foundation’s duty to preserve it. Dr Abela says that they are responsible for how the volumes are exhibited, as care must be taken towards even the simple act of opening a volume, as the binding and spine themselves tell their own story. She said that we need to change the culture of paper heritage, that the documents found in the Archives are just as precious as our Caravaggio paintings and our temples. When investing in an Archive, we are investing in our identity, our heritage and our culture.

She said that the team, staff and volunteers are extraordinary and they all take pride in their work and the collection. It is important for the people who work in the Archives to respect it and appreciate its value. She reflects on how she has grown throughout the experience and that now when she opens a volume, she appreciates the work, time and conservation that has gone into it. It is not a profession for the impatient, but one which gives a great deal of job satisfaction.

Projects and future plans to give back the well-deserved dignity for the Archives

After discussing corsairs and angry wives, Buhagiar showed this newspaper a video of the disgraceful state of the Notarial Archives when they were discovered in 2008: numerous volumes on wooden shelves, manuscripts and documents stacked carelessly on top of each other, all caked with dust. Dr Abela said that when she saw all this, she was ashamed that years of Maltese and Mediterranean history had been left to disintegrate.

Both Abela and Vanessa were excited to share the plans for the rehabilitation of the Notarial Archives, which have been granted sponsorship by the ERDF (European Regional Development Fund) 2014-2020. The Government is also sponsoring book and paper conservators, thereby encouraging more students towards the studying of conservation.

The Foundation has also collaborated with the University by funding five research projects, which look at various disciplines. One example of such research is highlighting the simulation of the Archives environment, therefore the archivists would know whether moving a document from one place to another could damage it. Dr Abela also explained the concept of a notarypedia, a form of a Wikipedia website which will expand and simplify the means of research for the general public by digitalisation of the Archives.

The Foundation is currently working towards giving the building housing the Archives the reputation and dignity that it truly deserves. They are currently undergoing a programme of restoration, which also includes the building next to the Archives. The two buildings will give the Archives a bigger – and more open – space. Vanessa explains that the current Archives will act as a store for the numerous volumes and will not be accessible to the public so that it maintains an environment that is ideal for the paper and manuscripts.

The other building, apart from having a conservation laboratory, will also act as a social hub, including a lecture room, museum, social space and even a virtual reality space. She goes on to highlight the importance of people with similar interests engaging in an environment which not only acts as a means of information, but also entertainment.

You cannot help being impressed by the sheer enthusiasm that the Foundation has for this fantastic and unique restoration project, which will bring something completely new to the capital. As Dr Abela points out, the team consists of people from many different disciplines, striving to deliver a high standard in their work and to be at the forefront of research and conservation.