The Maltese have for many years settled far and wide, and numerous such migrants have distinguished themselves in their respective fields. Roland Oreste Cassar was no different.

Born on 19 September 1934 in Alexandria, Egypt, Roland was a man of adventure - a boy scout with a penchant for exploration. When World War Two erupted in 1939, Egypt soon found itself in the thick of things with Alexandria playing a very important role on the North Africa front as Britain's main base. It was not however the rumbling tanks rolling through Alexandria, or the mammoth vessels anchored in the city's harbour that caught Roland's eye - it was the drone of the Rolls Royce Merlin engines, amongst other, flying overhead that were his source of daily fascination.

Aged 17, Roland moved to the United Kingdom where he achieved a degree in aeronautical engineering, before joining the British Aircraft Corporation on an apprenticeship. He stayed in Bristol for the best part of 13 years, and there his most notable assignment was his design of the vertical tail section of the famous supersonic airplane, the Concorde.

The Concorde is an unmistakeable part of aviation history, both in terms of the technology it employed - it is, along with the short-lived Tupolev Tu-144, the only commercial aircraft capable of going supersonic - and in terms of its design. In 2006 in fact it won the Great British Design Quest organised by the BBC and The Design Museum in London, beating other beautiful creations such as the Jaguar E-Type, the Supermarine Spitfire, and the BMC Mini in the process.

Saying that Cassar was merely responsible for designing the tail of the Concorde does not do justice to the complexity and genius required to manage such a feat. A conventional fixed-wing aircraft would have a horizontal stabiliser surface separate from the main wing at the craft's rear. Such an arrangement allows for a less complex design to reach optimum stability. However, the Concorde was no conventional aircraft.

The supersonic Concorde with its tailless and ogival delta wing design. Roland Cassar was responsible for the design of the vertical fin on the aircraft.

The main drawback of having a horizontal stabiliser surface is that it generates a lot of drag - not ideal when you want your aircraft to fly at supersonic speeds. An alternative had to be found, and so the Concorde was designed in such a manner to be "tailless". The tailless concept was not necessarily a new one: the de Havilland DH 108 Swallow, Northrop X-4 Bantham, the Dassault Mirage and the Convair F2Y Sea-Dart all had used tailless designs - with the Mirage becoming the most-widely produced Western jet aircraft and the Sea-Dart becoming the first (and only) seaplane to break the sound-barrier. The question however was whether this concept could be adapted to a commercial aircraft.

To compensate for the loss of stability that would come as a result of the removal of the horizontal stabiliser, the Concorde was designed with beautifully curved ogival delta wings - giving the aircraft its synonymous shape. Cassar's vertical tail fin design was a vital part of the aircraft, and of its unforgettable image. The Soviet Tupolev Tu-144 - the only other supersonic commercial aircraft - also had a very similar design concept to the Concorde, although it was much more short-lived than its western European counterpart: The Tupolev may have made its inaugural flight and gone supersonic a couple of months before the Concorde - but it was only used for passenger service for a year while the Concorde remained in active service for 27 years.

Cassar was not working with BAC when the Concorde made its inaugural flight in 1969 though; in 1965 he flew across the pond to work with the Douglas Aircraft Company having been recruited to work on the tail arrangement on the Douglas DC-8-60 and DC-9-20/30 - two aircrafts which would go on to see extended service as airliners. His work quickly expanded to include the design criteria, loads, stress, fatigue, and formal documentation for FAA certification.

When Douglas merged with McDonnell Aircraft to become the McDonnell Douglas Corporation in 1967, Cassar was installed as the Principal Engineer Scientist for the Structural Analysis Group and was in charge of the structural design criteria and loads for nearly all McDonnell Douglas' new airplanes. Notable examples include a DC-8 based AWACS concept (Boeing's E3-Sentry was selected ahead of this concept, with the sentry still being in use today), a military adaption to the DC-9 called the C9B, the DC-10-20/30, and the YC-15, a prototype four-engine short take-off and landing tactical transport plane. The latter prototype was never adopted, but it served as the basis of the McDonnell Douglas (later Boeing, after the two companies merged in 1997) C-17 Globemaster III.

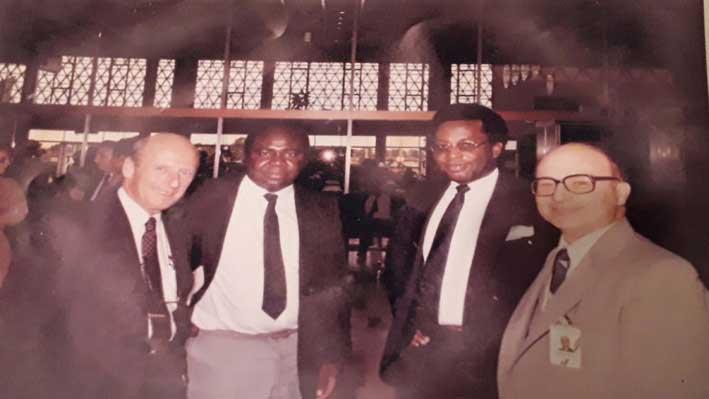

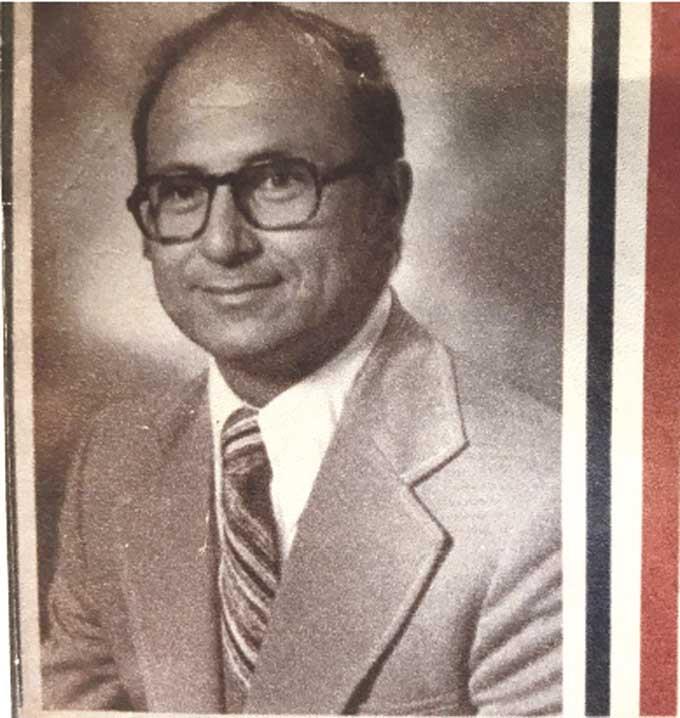

Roland Cassar in his McDonnell Douglas days.

Besides being an exceptional engineer though, Roland was also a great linguist and could speak fluent Italian, French and a little bit of Arabic as well. This made him a valuable asset for the company, and he travelled extensively to market the DC-10 design criteria to foreign airlines. The DC-10 saw 20 years of service as a passenger aircraft and today is still used as a cargo plane by companies such as FedEx.

In his personal life, Roland married Greta, whom he met when he lived in Bristol, and they lived together for 56 years before Greta passed away in 2011. He visited Malta very frequently especially after his retirement, partaking in a number of family reunions over the years. After Greta passed away, Roland married Merete Barrett on 24 June 2012. He passed away at the age of 84 on 27 December 2018, leaving to mourn his wife, two children, seven grandchildren and six great-grandchildren. A memorial service will be held on 17 February in Fairhaven, Santa Ana in the state of California.