It was September 1997. I was about to join the UN's "oil-for-food" programme designed to counteract the effect of sanctions on the Iraqi people. The UN Security Council Resolution 986 allowed Iraq to sell enough oil to pay for the population's needs in food and medicine, a programme to be administered and monitored by the UN. In parallel, the UN Special Commission (UNSCOM), an inspection regime was also created by the UNSC to oversee Iraq's compliance with the mandate to destroy, render harmless or remove all Iraqi biological, chemical and nuclear weaponry.

The UN plane landed on a bumpy pot-holed runway and stumbled over to what was left of the Habbaniya military airport 20km outside Baghdad. Through the airplane windows, we saw abandoned hollowed out buildings and destroyed military planes. After Iraq's invasion of Kuwait in 1990 and the ensuing Gulf War against Iraq, heavy sanctions were imposed by the UN Security Council. Our plane was to be the last UN flight as Saddam decided to retaliate with his own sanctions. He forbade the UN to fly planes into Baghdad air space - thus forcing UN staff to endure around 12 hours on the long and monotonous highway linking Baghdad to Amman and the outside world.

As we left the plane, we were hit by a blast of hot air heavy with dust - a mini desert storm. It found its way into our nostrils, our eyes, our ears, our mouth, our hair, our clothes. Soon we were ready to be deep-fried under the relentless sun. We then drove several miles to the Canal Hotel in central Baghdad, where the UN offices were housed. (On 19 August 2003, Canal Hotel was largely destroyed by a suicide bomber who drove his truck up beneath the window of the UN Special Representative Sergio Vieira de Mello. He was killed together with 21 other people and over 100 more were injured physically and psychologically.)

I had been in Baghdad before and was curious to see if anything had changed. It had - for the worse. A few years earlier, the pleasant streets and lovely avenues were animated with people going about their business. The war was over. There was peace, hope, a future. Now, sanctions had taken their toll. Palaces lay derelict, witnesses to the grandeur that was once Baghdad. Palm trees lining the once majestic avenues were drooping and covered in dust. Even the magnificent Tigris and Euphrates seemed muddy and lifeless and the once bustling fish restaurants on their banks were now empty and ghostly.

The Baghdadis looked weary. They dragged their feet in worn out shoes. They looked as miserable as their city. Hope had been replaced by sorrow and dejection. The malnutrition rate in children had risen astronomically - a clear signal that food was insufficient both for children and adults. A cry of alarm was raised by UNICEF when a study published in the Lancet found that over 500,000 children had died of malnutrition and related illnesses since the imposition of sanctions.

Iraq was unable to pick up the pieces to restore public services. The water supply, the electricity grid and the sanitation system had been decimated. Schools were damaged or destroyed. The hospitals could not function as they did not have the drugs, equipment, power, water, staff, etc. required to provide the badly-needed services. And, food and medicine were in poor supply. It was clear that, as it stood, the "oil-for-food" programme could not make much of a difference. It absolutely had to be broadened considerably to include repairs to the infrastructure viz. clean water and sanitation services, a reliable electricity supply, as well as rehabilitation of schools, education services, animal health, etc. In response to recommendations based on our findings, the UN Security Council agreed that funds had to be increased multifold (from $1.6bn to $5.2bn every six months) to cover all the additional requirements.

UN staff were not allowed to rent property. We had to live in specified apart-hotels. I had a simple serviced apartment in the Summerland Hotel. It was my home. My phone would jump to attention every time that I entered. I was never alone. I had been warned that, in Baghdad, even the trees had ears and that mirrors had eyes! I covered my mirrors with beautiful scarves. I turned my TV on maximum volume every time I talked. I became alert and vigilant as this intrusion on my privacy was very disturbing. The first time I went into an Iraqi home, I was shocked at the loud blaring TV which made talking almost impossible. I asked my host to lower the volume. A dance of signs followed indicating that the walls had ears as had every electronic device, and so on and so forth. I noticed that every person on the street was a potential spook or informer or simply scared as people invariably noted my car's number plate whenever I stopped somewhere and did the same when I left - but they were not the same people as when I had arrived. I couldn't fathom what the point of this exercise was.

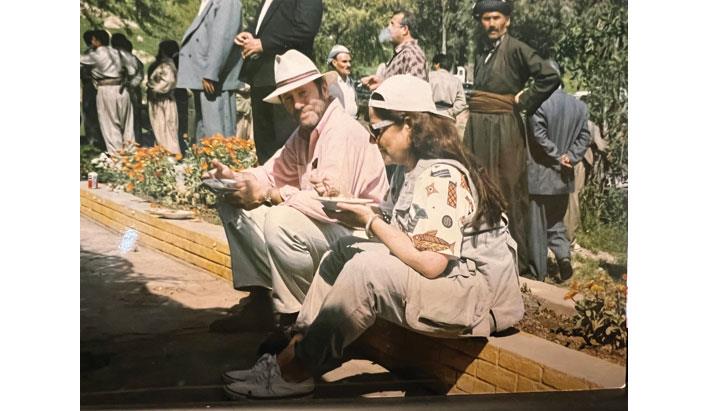

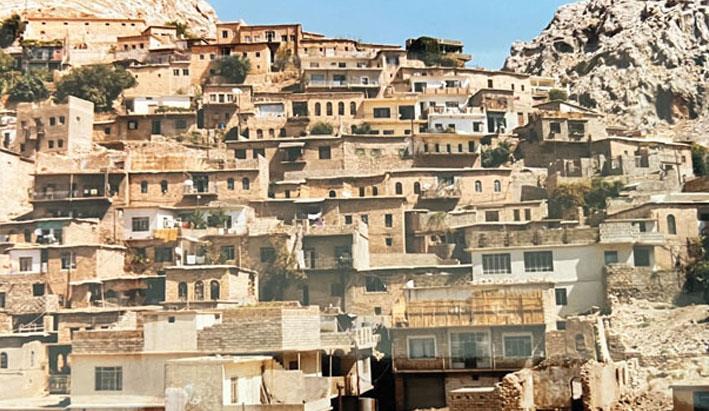

Although our movements outside of Baghdad were restricted for security reasons, work took me all over the country allowing me to visit some of the most important ancient and sacred places in Mesopotamia, also known as the cradle of civilization. It was a welcome respite to step back in time albeit briefly. In my mind, there was no doubt that Iraq, like the Phoenix, would rise again from the ashes the way that it has always done. Unfortunately, that day has still to come.

I set out to find old friends who I had met on previous visits. Gadi, a young pianist, and his family still lived in the same house in Mansur, a once elegant part of Baghdad. Their hospitality had not changed despite the scarcity of absolutely everything. Gadi's sister, Ban, who had a marvellous soprano voice, was awarded a scholarship in Leuwen, Belgium. However, she returned to Baghdad before completing her studies. She was homesick and preferred to be back home facing the hardships with her family rather than worrying about them while living in comfort in Leuwen. She sang to us accompanied by Gadi on the piano. Unforgettable moments in the strange limbo that Baghdad had become.

Ami never gave up her Tuesday night literary evenings in the back garden of her bookshop on Al Rashid Street. Her garden was fragrant with jasmine creepers and roses - a little haven on the banks of the Tigris. And her literary evenings were a delight as Ami's friends were artists and intellectuals seeking respite from their enforced isolation in a congenial atmosphere. After the readings, we would spend hours chatting in the shade of frangipani trees sipping lemonade or mint tea. Small wonder that Will and I found love there listening to Iraqi poetry accompanied by the strings of a Stradivarius violin.

The bookshop had been transformed into a treasure trove of unusual artifacts, silk hangings and throws, antique bed linen and towels and some other items whose significance Ami explained to me. I spent several wonderful hours with Ami learning about Iraqi customs and traditions. My wedding gown - a lace robe embroidered in silver thread - came from Ami's bookshop. It remains one of my treasured souvenirs. Sadly, families were forced to sell their family heirlooms to pay for basic necessities. Some even sold their furniture, their musharabiya (shuttered) windows and screens, their carved Baghdadi doors, artworks, silver and antique books, in order to survive. Auction houses flourished selling precious items to greedy diplomats who spirited them out of the country thanks to their diplomatic immunity.

Whenever I found the time, cafés in Baghdad were always a great place to spend time sipping Arabic coffee, surrounded by men of all ages wearing their heavy moustache, smoking the ubiquitous nargileh (waterpipe) and watching life go by often in silence. Shabandar and Um Kalthoum cafés were wonderful with their walls covered with pictures of past and present celebrities. Unusually, people were always ready to speak to foreigners. Shabander Café is located in the iconic Muthanabi Street (named after a poet of the 10th century), a street full of bookshops, bookstalls, cafés and galleries with books of all kinds covering the sidewalk. On Fridays, there was always a book market where intellectuals and students vied for the precious books. We met several contemporary artists, whose work was very moving, almost heart-rending, as it reflected the pain the Iraqis were experiencing in the recent past. The few pieces that hang on the walls of my home continue to bring back the same mixture of pain and beauty.

It is not surprising that Christmas 1998 is one I will never forget. We lived through the four-day Operation Desert Fox, United States' "precision bombing" from 16 to 19 December 1998. Key Iraqi security buildings, located close to our Canal Hotel office, were targeted. The sky around us lit up with the relentless fireworks display. We were assured that the UN building was safe. Safe? The whole building shook and windows shattered. So did the nerves of the calmest of my colleagues. It was common knowledge that the UNSCOM inspectors, who were whisked out of Baghdad before the bombing started, had left behind locked doors several samples of anthrax, niacin, mustard gas and other toxic materials in their fridge. Just one leak could have been lethal. The worst was avoided but the experience frayed irreparably the tenuous relationship between the humanitarian and the political staff.

The humanitarian staff were finally evacuated to Amman on buses, just as the bombing petered out. We could see the last of the fireworks fade away in the sky behind us. It was almost Christmas. The staff had been through a traumatic experience and a few days in Amman would have been the ideal cure. The consensus was to spend Christmas in Amman. But, for some unknown reason, we were instructed to return to Baghdad immediately. We set off again on the endless dusty highway to reach Baghdad on 24 December. On arrival, we were told that Christmas celebrations had been cancelled by the UN hierarchy as a sign of respect toward our Iraqi colleagues. Nobody was in the mood to celebrate. Baghdad was in shock. The streets were deserted. Our Iraqi colleagues and friends were heartbroken and their children's dreams shattered. All vestiges of hope and peace had vanished.

A group of us attended midnight mass at the Catholic Church where Ban sang the same Christmas carols as she always did. This year, her beautiful singing was all the more poignant. Many of us shed a tear that night. Mass was followed by breakfast in the priory. And, on Christmas Day, we managed to rummage together enough food and drink to create a semblance of a Christmas meal. Our hearts were heavy with sadness as we commiserated with the Iraqis. This just had to be the saddest Christmas of my life.

My assignment lasted two years. I had to return to Geneva in August 1999, sad to leave Iraq but relieved that the UN programme now covered most basic services. However, my relief was short-lived as the "Shock and Awe" invasion of March 2003 brought devastation once more to the Iraqi people. And their suffering is not yet over.

The Author

Margherita Amodeo grew up in Malta. In l974, she joined the United Nations in NYC, later moving to Vienna and Geneva. She soon realized that her calling was in the field. Afghanistan, Cote d'Ivoire, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iraq and Mali are just a few of the places where she worked - mainly in communication. She holds Master's Degrees in International Relations and Economics and, after leaving the UN, she embarked on a new journey in the field of the arts, creativity and psychotherapy.