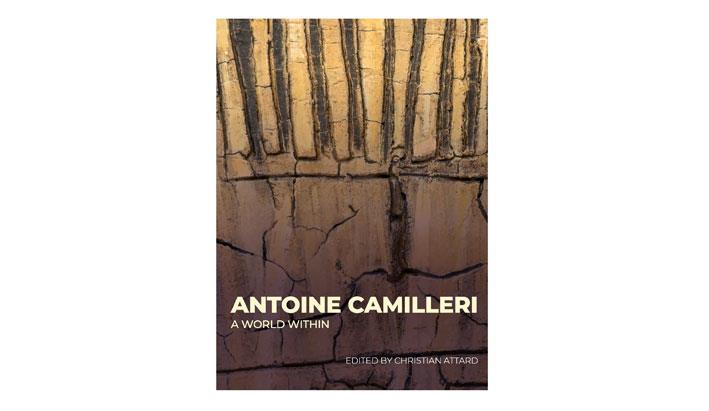

The launch of Dr Christian Attard's Antoine Camilleri - A World Within published by Kite Group took place at Gallery 23 in Balzan, last week. It was 'full house'. At the same time one could admire the exhibition of Antoine Paul Camilleri, Antoine's son, who too, is an able artist. He not only draws and paints but is also an excellent etcher, ceramist and sculptor.

The editor of the book, Dr Christian Attard, Prof. Joe Friggieri, Prof. Giuseppe Schembri Bonaci commented on the book and its contents. Both Professors Friggieri and Schembri Bonaci also have contributions in the book.

Below I am reproducing Dr Attard's comments:

"The first time I came to know of Antoine Camilleri was somewhere in the early nineties when our lecturer, now my friend, Lino Borg, took us to his Kantina studio, in Old Bakery Street, Valletta. It was an unforgettable experience. The dark, meandering spaces of the Kantina, its walls covered with Antoine's compelling images, were conducive to a spiritual experience. It almost felt like entering a sacred cave, a lost cavernous space, lost to space and time. And then the high priest himself entered, with his white, shoulder length hair and his deep voice. And he talked to us, a class of teenagers, young university students, about his life and works.

Antoine loved an audience and I, like most of us there on that day, was completely hooked. It felt that this is what art should be all about. Spiritual, experimental, immersive, religious, compelling, provocative, exciting. I still think of art along those terms. I still think that good art should have those characteristics. I was to visit the Kantina on another occasion or two and later I even managed to visit Antoine's other studio, on the top floor of an old palatial residence in Zachary Street, Valletta.

I hope that this book Antoine Camilleri - A World Within does capture something of this magic. I am reminded of a book I have read by Julian Spalding called The Art of Wonder. Spalding used to be the director of various galleries and museums: Sheffield, Manchester, and others. The main idea proposed by Spalding is that to enjoy and understand art all you must do is to look at the world around you and respond to it emotionally. This is obviously counterintuitive to all that somebody like me does. We argue about art in an intellectual manner, we discuss the different methodologies we are to employ when studying or writing about a work of art - looking at the stylistic aspect, the technical; we do a formal analysis perhaps, tackle the work from a social/historical aspect. But like Spalding advises, we must keep a sense of innocent wonder when we look at works of art, and in a way, Antoine's work do lend themselves to this kind of way of seeing. He used to work very intuitively, I am a feeler and a doer he used to say. Antoine himself did keep this sense of wonderment throughout his life.

This book does try to keep alive that sense of wonderment. If anything, it is full of photographs, more than 400 works are illustrated here, so in a way, one can 'read' the book without reading a word, but only by looking and studying the images. There are two whole chapters in this book which are purely visual; images accompanied by very short captions. Even when it came to Antoine's biography, we opted for a visual manner of narration. Like the photo-romance popular some decades ago, one could move from one picture to the next and see Antoine as a toddler or a young boy; Antoine taking his first tentative steps in the world of art; Antoine in his studios etc. So yes, it would be perfect for any potential reader of this book to disregard the texts, at least initially, and just look at the pictures. One should first be engulfed with that sense of wonder. Exactly like that sense of wonderment most of those 90s art students felt upon descending into Antoine's Kantina.

Another chapter, 'A World Within, A World Without: The Conflicting Eye of Antoine Camilleri', considers Camilleri and his artistic output within an academic field termed 'visual culture'. It is a study that aims to weave webs of connectiveness between Camilleri's art and the cultures that influenced it. Camilleri's approach, however, was almost always nuanced and there might not always be an obvious link between the visual and the cultural, between the signifier and the signified and consequently between the visual possibilities Camilleri creates, the meanings they engender, and how such meanings would have reflected back on his proposed visuals. Camilleri typically internalized his many influences and what he produced was allusive, poetic, and personal, although he was very rarely wilfully obfuscating or esoteric. The teacher, father, and grandfather within him stayed his hands. This chapter, as the title suggests, is mainly concerned with the manner Camilleri threaded his way between the world outside of him and that within him and how he tried to reconcile the two, in the process creating a visual language that is in many ways the result of this dialectic.

Giuseppe Schembri Bonaci's in-depth study of two of Camilleri's most iconic works, namely Preghiera and My Life-My Work, forms the gist of the third chapter. In essence these works are collages of several older works by Camilleri himself, but which are here photographically replicated and reproposed. Both function like a cabinet of curiosities or, as Schembri Bonaci analogizes, like Orhan Pamuk's Museum of Innocence. This study intellectually unfolds these works, aiming to parse their layered meanings. In the process, the author forges interesting connections between the past and the present; between the private and the public, and ultimately between himself and Camilleri. This chapter is in essence an original and personal, perhaps post-modern contemplation upon these works. For Schembri Bonaci is only marginally interested in Camilleri's original patterns of intention, to appropriate a memorable Baxandall phrase. Better still, he finds connections that were not, or could not, have been known to the artist, if not in an unconscious, oblique manner. The links Schembri Bonaci forms and the interpretations he makes are thus as much his as they are Camilleri's.

Antoine Camilleri's thought-processes must have been primarily visually driven, but it was typical of him to add words and quotes to his drawings, as if some ideas of his needed the power of words and images working in tandem to start taking shape.

Joe Friggieri's chapter, entitled, 'Antoine Camilleri's sketches, epigraphs, and quotes', deals with this phenomenon which is especially present in the artist's exploratory sketches but occasionally also on his finished works. There is a telling detail in one of Leonardo da Vinci's codices, the Codex Arundel. In one corner of a folio which brims with geometric analyses, the Renaissance master scribbled the words 'perché la minestra si fredda'. For a second it seems that Leonardo's grumbling stomach must have taken the better of him, his lofty ideas suddenly giving way to plain hunger. Camilleri's drawings and writings might similarly move from the philosophical to the pragmatic, or fr om the religious to the down-to-earth. They might be the kernel of an idea, occasionally a fully formed concept, or even a throw-away remark; whatever they are, as Friggieri explains, they mostly open a window upon Camilleri's interests and thought- processes."

om the religious to the down-to-earth. They might be the kernel of an idea, occasionally a fully formed concept, or even a throw-away remark; whatever they are, as Friggieri explains, they mostly open a window upon Camilleri's interests and thought- processes."

Commentaries over, discussions continued and Antoine Paul's artistic works admired as we enjoyed a glass of wine (or several) and canapés. I finally dragged myself home, well past my bedtime. Gallary 23 has become quite a hub of culture.