Carnival in Malta is one of the most important cultural festivals on the island, dating back to the 15th century with the arrival of the Order of St. John. Certain historians may suggest that Carnival was not a Hospitallers’ innovation. Professor Stanley Fiorini proposes that there are documents which record Carnival dating back as early as the 1400’s and that with the rise of Christianity it was transformed into a wild, spontaneous festival celebrating the beginning of Lent marked by fasting, hence the etymology from the Latin expression carne levare (remove meat).

The Notarial Archives are bursting with records, which shed light on numerous aspects of Maltese life and customs that have been forgotten over the passage of time. Alongside numerous legal documentations, the Archives are also home to notarial deeds documenting the performance of dancers and musicians who appeared in front of notaries to entering into agreements with official entities or private patrons, especially for the Carnival period. Such legal documents give us a different narrative to Carnival which many may have not explored or discussed yet.

Although the scandalous costumes, delicious treats and colourful floats might steal the show and hearts of many during the Carnival festivities, the parades are just as important and have historical significance. Officially, the Carnival would open with a light-hearted sword dance (parata), which was a dance that commemorated the Order’s conquest over the Turks in 1565.

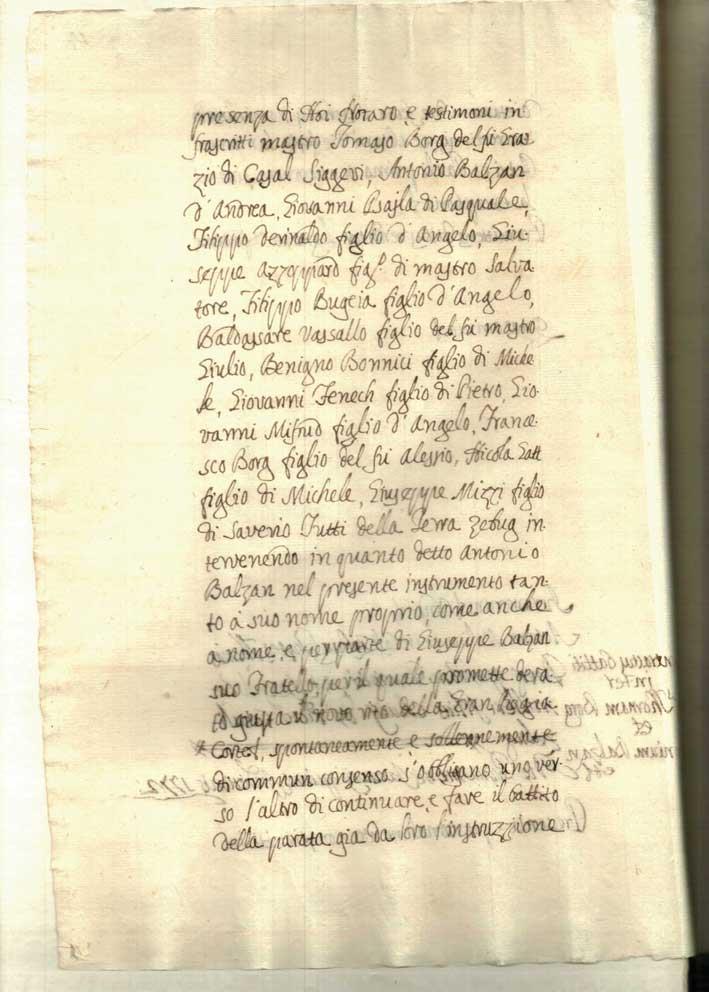

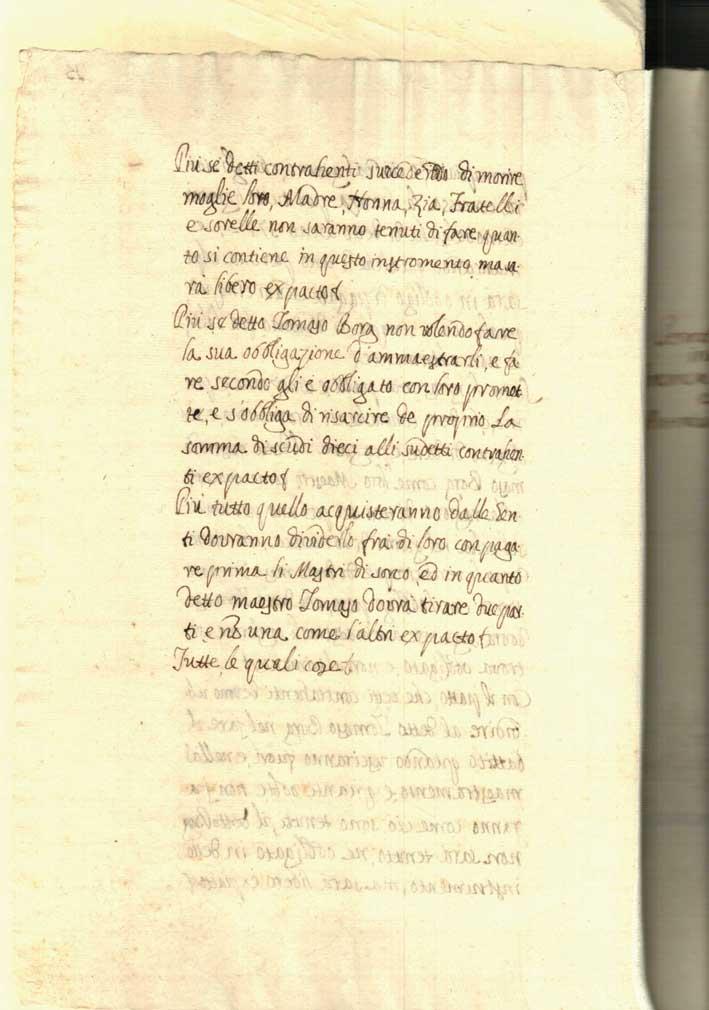

One would find a contractus battiti at the Notarial Archives between Thomaso Borg, Antonio Balzan and others dating back to January 1772. Vicki Ann Cremona has explained that the term battiti is a unique reference in Maltese history. Reflecting on the text it would most likely be some form of dance which involved a leader/conductor and 10 individuals, which were all men. In the contract the main action of the dance is described as ‘fare il battito’ implying the beating of wooden swords as the dancers are engaged in a mock fight. The contract indicated that the parata dancers had to obtain an official licence for each day that they danced during Carnival and anyone who did not turn up would have to pay a fine. The missing dancer would be charged 5 scudi which would be equally distributed among the others.

The contract also stipulated that any money earned during the performance was to be divided equally among the dancers. Maestro Tommaso Borg, who came from Siggiewi must have managed the group’s finances as the contract labelled him as the group’s banco and that he was to be given a sum of six tareni by each dancer, therefore getting double of what the dancers were earning. The Maestro was also given two parts of the earning for his efforts.

The essential nature of the deed was to fix the monetary rights and responsibilities of the individuals and dancers. The fact that there was a signing of a notarial deed showed that the dance must have been popular and profitable. Such documents are an essential part of Maltese heritage and give a bigger insight into what everyday life on the island was like in the past. These particular documents have given cultural historians a deeper understanding of the rights that such entertainers had during the Carnival festivities.

Such documents are an essential part of Maltese heritage and give a bigger insight of what everyday life on the island was like in the past. They also give historians a clearer indication of one of the oldest celebrated traditions on the Maltese Islands and to open more discussions regarding the history of Carnival.