There are literally skeletons in the closet upstairs at the Main Guard on Misraħ San Ġorġ in Valletta. Two crouching painted skeletons prop up either end of a door frame leading to offices recently vacated by the Attorney General. In each of them, in cupboards created by arched vaults, a further two skeletons lie supine painted against a brick background. One of them is being tempted by the devil. In the same room, another skeleton dressed in a friar's robe, painted in 1881, has had his eyes gouged out.

The painting has a number on it, one of a concentration of overlapping wall paintings and designs dating back to the mid-19th century, many of which were inventorised in a catalogue compiled by British soldiers during their occupation of the building.

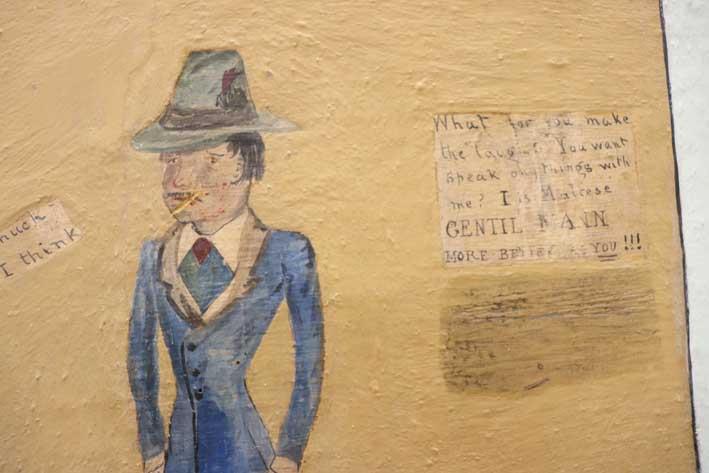

"What for you make the 'laugh'. You want speak any things with me? I is Maltese GENTIL MAN. More better as you!!!" reads the text accompanying an insert lampooning a caricature of a Maltese dandy. To the right of this panel, two flags of the Kings Own Malta Regiment, painted in 1972 by Adrian Strickland, assisted by the late Paul Debono and Louis J. Sant Cassia, replace the actual banners which once hung there, their brackets still visible. Great care was taken to paint the flags as though they were in the background so as not to overpaint the pre-existing paintings, including a dragon, a polo player and copies of lithographs of hunting scenes, which they have circumvented.

This approach pre-empts that taken by the team of Heritage Malta conservator-restorers. The skeletons once sat on a green dado that skirts the large officers' mess where the majority of the paintings are situated. However, the dado is now significantly higher. "We have to respect the history of the wall; we cannot go back to the original." This is a point that Anthony Spagnol, senior conservator within Heritage Malta, is keen to convey. "Where possible, we must reveal without cancelling any aging. If the intervention changes any part of the painting's current state or reverts to an earlier version of a regiment's uniform, you are tampering with history."

Although exploratory research commenced as far back as 2013, actual restoration work started in 2018 based on groundwork undertaken by Heritage Malta conservator Ritianne Psaila, who submitted an in-depth report on the wall paintings' condition, their manufacturing techniques and previous interventions. Anthony, in a supervisory role, is being assisted by conservator-restorers Sofia Almagro from Spain .

An assessment is made of the damages a wall painting has suffered. One of the images, which presented the biggest challenge, is an Allegory of the Father Time carrying a scythe. Originally his missing hand held a clock that once hung over the fireplace. "There was a lot of water infiltration in this area, causing extensive deterioration," Sofia recalls.

Most of the paintings were executed by officers with plenty of time on their hands. Originally called Guardia della Piazza, as the name implies, the Main Guard was built in 1603 as a guardhouse by the Order of St John and later the guards of the Governor of Malta, who resided in The Grandmaster's Palace just across the square. Although it once served as the Libyan Cultural Centre, the building has always been a symbol of British Rule in Malta. On the relief of the British coat of arms, above the colonial addition of a neoclassical portico, the Latin inscription reads: "The love of the Maltese and the voice of Europe assigned these Islands to great and unconquered Britain. AD 1814."

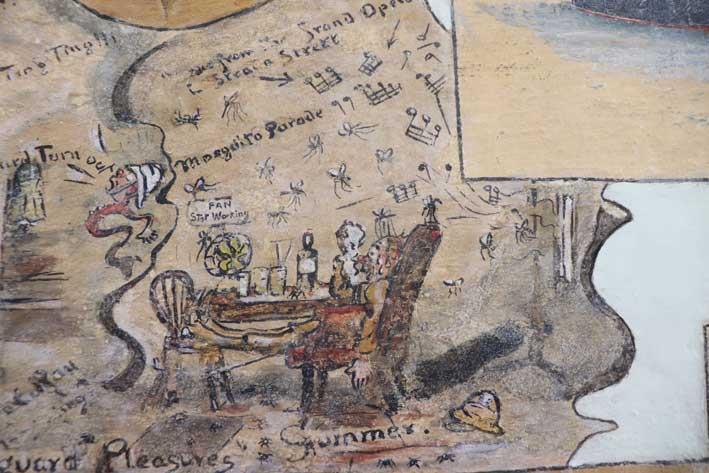

I ask Sofia which painting she has enjoyed restoring most and she leads me to one satirically entitled Main Guard Pleasures, which is divided into two sections. The Winter section depicts the monotony endured by a British officer repeatedly rushing downstairs to stationary guard duty. In the summer section, the fan has stopped working, mosquitoes parade to the sound of opera wafting in from Strait Street, located behind the Main Guard, while a sweating officer lays slumped on an armchair, fanning himself. "It's true, it is really hot here in summer and you can still hear music coming in from the streets," Sofia laughs, identifying with the comic scene.

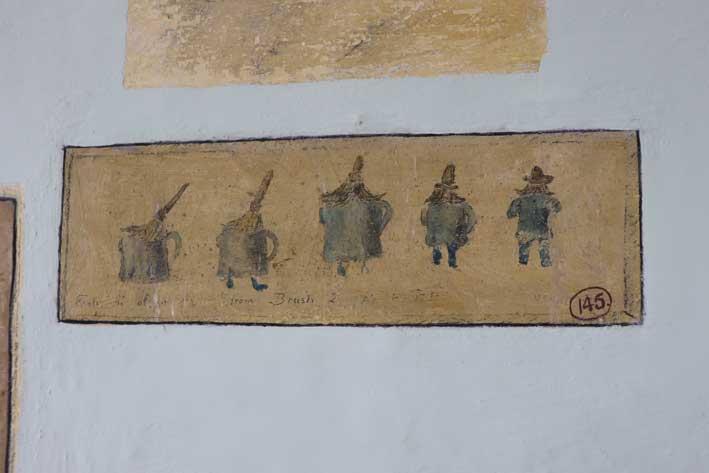

The walls are a snapshot in time, alive with every day scenes in Valletta. There is a monochrome painting of a woman in a faldetta trailing a priest wearing a cassock and a wide brimmed hat. There are processions and parades, pictures of sweethearts and ladies of more dubious repute, military insignia, sea craft and a surrealist sequence where a brush and tankard metamorphosise into a man.

The words "behind these sorry relics, once stood a sorry gut" accompany a moustache, glued to the wall, bequeathed to posterity by its owner. Some of the paintings are trompe l'oeil attempts to give three dimensionality to objects that once stood in their stead. A shelf painting with a book on it lies adjacent to a painting of a hook in the wall (ganġetta) that originally held a door open. Likewise, paintings of a hanger and swords substitute the actual items which hung in situ.

"The ongoing work at the Main Guard is a hallmark of how conservation and restoration should be carried out. Heritage Malta is setting an example of the standard we wish to maintain," Spagnol states proudly. The public will be able to appreciate all the hard work carried out behind closed doors when the Main Guard enters its next reincarnation as an interactive visitors' centre for historical sights in Valletta. The forgotten longings, aspirations, and observations of these officers will come back to life when these walls speak again.