"During the partial lockdown period because of the COVID-19 pandemic I obeyed the health authorities and remained at home with my wife, Angela, to stay safe. We had ample time for spring cleaning and I had a holiday from shaving. But social distance meant also not meeting our children and grandchildren, following livestreaming masses on television, and wearing masks when talking to the postman. And the university had closed all its services to students and instructed all its academic and administrative staff to work from home via the web.

Therefore, I had to make more use of the dreaded online functions for delivering learning material, assessment, and feedback to my post-graduate students of Translation through the Virtual Learning Environment system. I also became familiar with Zoom because like most of the rest of the world our university switched to online sessions for remote work. I had to use Zoom for distance education (lectures and individual tutorials), assessment (on assignments and in vivas), and social meetings (like peer-to-peer chatting and departmental sessions). At the same time I saw myself engulfed in an atmosphere of science fiction and I imagined myself to be a character in some cheap fiction dealing with scientific advances that enhanced human distancing. This was, however, reality.

One day I was (in my study) hosting a meeting on Zoom. It was a viva voce and we were examining an M.A. dissertation of a student. Half way through the viva, I heard my wife, Angela, in the other room softly playing Louis Armstrong's What a Wonderful World. I smiled because I thought she was being sarcastic: scornful about the lockdown and sardonic about the Zoom meeting (notice the alliteration of the song's title - WWW).

Prof. and Mrs Briffa and their grandchildren, the latest, Amy a girl

When we ended the Zoom meeting, I looked out of the window overlooking our garden and there, under the orange tree, I saw Angela surrounded by sparrows: she was feeding them pieces of bread. She would throw some pieces to the right of her and the sparrows would dive after them; then she would throw some other pieces to the left and some of the dear creatures would shift to where they fell. I joined her and she said excitedly: "This is lovely! I discovered these new friends yesterday while removing some weeds and I saw them watching me from the top of the tree. And I said to myself: 'How about giving them some crumbs!' And they liked the idea. Look at them." She wasn't being sarcastic, after all. And in my mind two images came: Walt Disney's Snow White and Mary Poppins' Feed the Birds. My wife had found something beautiful during the pandemic period.

Spending more time at home meant that I could dedicate more periods on my research and studies so that the pandemic would not seem dystopian. I embarked on various related projects on translation, literary criticism, stylistics, the study of Maltese and its anthropological culture, and education. In fact, during this period I undertook intensive research on work relating to experimentation with various language aspects. The major part of this research involved the cultural investigation and analysis of institutionalised language, the writing of several studies on contemporary Maltese literature, and the writing of translation studies in Maltese with the aim of organising translation theory in Maltese.

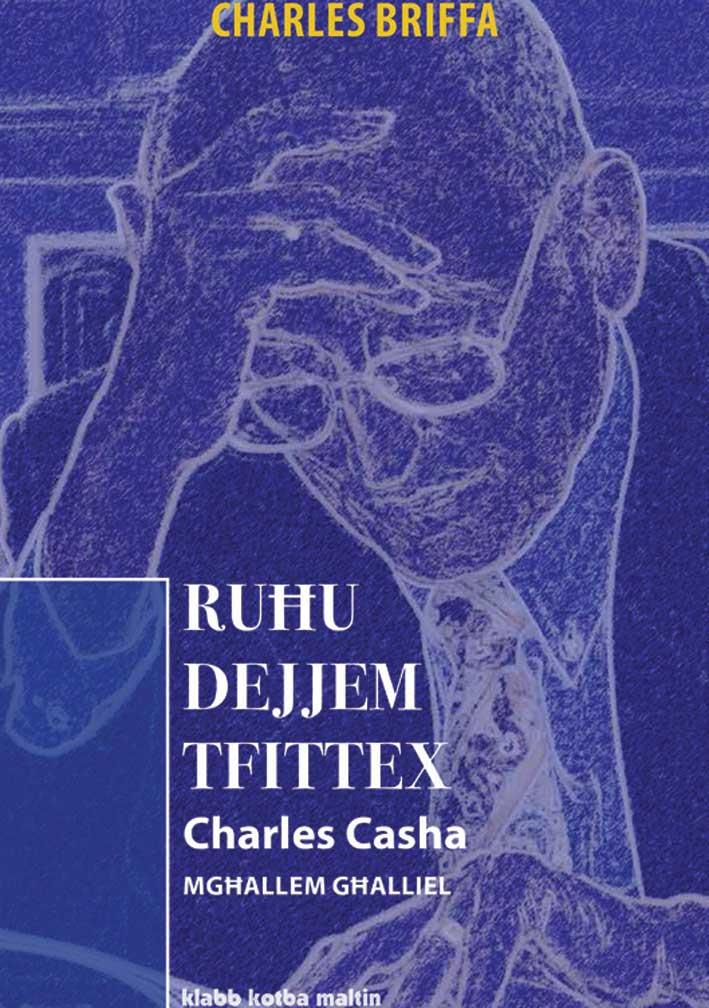

Just before the lockdown I published Dellijiet Jgħajtu fir-Ras - Mario Azzopardi: Poeżija, Narrattiva, u Kummiedja Soċjali, and its launching had to take place on campus but it never happened because all public appearances had to be cancelled. This was another work in my series on living Maltese authors, and it was followed (during this Covid year) by Ruħu Dejjem Tfittex - Charles Casha: Mgħallem Għammiel. In this series I try to show that literature is an art of language that our authors engage in: certain unifications of words can generate thoughts and sentiments that others do not generate.

In Ruħu Dejjem Tfittex, for instance, I tried to explain how Charles Casha gives such a job to Maltese literature. He creates a poetic province through the art of language: all possible ideas, human actions, and feelings in the common world are placed in a fitting relationship with the readers' general sensibility. When I read his poetry I frequently feel that my consciousness is being invaded by an existence that is similar to my state. Casha's poetic function is not merely to experience the poetic situation, but to create it also in his readers. And in my book I touched on the transcendent assets of virtues and elegance that develop in his poetic mind.

Then in his creative prose Casha is mostly concerned with common contemporary reality to describe subjects and attitudes. Prose for him is a vehicle of the consciousness that must be directed towards assessing the quality of life in terms of the characteristics of the people found in the narratives. The whole range of his writing offers a valuing of personal life that attends to the general human life. Furthermore, his books for children are full of stories which provide a rich source for probing the young audience's imaginative responses to literary situations. Even his humour, at times wittily compact, is a verbally elated flowering of comic situations - as found in the stories of the unforgettable Fra Mudest. I tried to show all these artistic efforts through language in Ruħu Dejjem Tfittex.

In the early part of 2021, my wife and I are still prudent and deeply responsible by keeping distance and criticising mask refuseniks. Like everyone else, both of us still hope for better times. But she intends to keep her feathery friends as I continue being engaged in the ongoing search for archetypal patterns in Maltese institutionalised language.

And, by the way, the Covid experience increased the Maltese vocabulary.

Editorial Note: If you wish to contribute your own Covid diary please email [email protected]