Charles Xuereb

"The most interesting problems facing Maltese people are probably cultural and those related to identity." This succinct judgement by French migratory researcher, Claude Liauzu, when writing the history of migration in the Western Mediterranean region, accentuating the fate of Maltese settlers in Algeria at the height of migration to North Africa, puts emphasis on what Henry Frendo writes about in Diaspora. This volume, however, goes much further than that; it reaches out to wherever and however the Maltese emigrant dared venture around the globe.

In fact Frendo's thick volume does not limit itself to Mediterranean port cities, also including Eastern enclaves for that matter, but thoroughly covers destinations to which Maltese migrants sailed to since the beginning of the 19th century.

This rich collection of papers, features, public presentations and addresses, which Professor Frendo researched and delivered between 1985 and 2018, extensively deals with colourful human stories of emigrants from the Maltese islands, most of all those experienced by thousands that used to settle initially in the Mediterranean and later, especially after WWII in Australia.

The author believes that Maltese and Gozitans settled in some 194 countries (practically all the countries in the world) with a total diaspora of about 420,000. In this book, he tracks down unusual adventures of those, who in their search for a new life, outreached to far-flung places such as Louisiana in the United States, Zimbabwe and South Africa and Japan in Asia, sometimes tracing their ancestors back to centuries before.

Frendo's textual and photographic evidence does not only provide data for future archival purposes and curious reading. The author conjures a personal diary - mostly after he himself and his family became emigrants in 1978 - of his travels and migratory pauses on various continents while working for international migrant agencies, investigating records of Maltese settlers anywhere he goes.

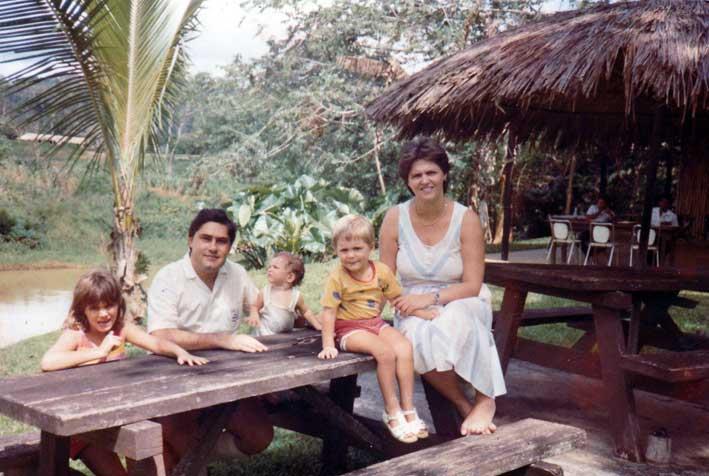

Henry Frendo with his young family on Papua New Guinea before taking up residence in Australia. Their siblings, say the author, were each born on a different continent. They returned to Malta in 1988

Henry Frendo with his young family on Papua New Guinea before taking up residence in Australia. Their siblings, say the author, were each born on a different continent. They returned to Malta in 1988

A Maltese pasha in Egypt

Diaspora is an anthropological anthology. Names and surnames of Maltese protagonists keep popping up from its pages with vibrant adventures of how they reached their chosen land, why they remained there and what they left behind, like Bianchi Beach in Egypt and Limnaria Bay in Greek Kythera or the prominent commercial business of Bugeja in far-off Queensland, first inhabited by Aboriginal Australians. In Egypt, the author also digs up stories about a Maltese pasha, a certain Bernard, who was involved with Carter in the Tutankhamun excavation in 1922 and descendants of Maltese patriot Giorgio Mitrovich from Senglea. Maltese patriot Manwel Dimech, who died in exile 100 years ago in British custody in Alexandria, is given a deservedly long chapter.

While outlining the history of these travelling compatriots - often accompanied by pioneer pictures - Frendo analyses the reasons why they decided or had been constrained to leave their homeland.

Realising there was a problem with population growth and financial restraints on colonial budgets, British authorities, on taking over the Island Fortress had almost immediately encouraged emigration to other British colonies within the Empire. One of the earliest such destinations was the Ionian Islands, where first British Malta governor Thomas Maitland, after 1813 had his other governing foot.

Maltese settlers in the Ionian Islands receive a fair share of attention from Frendo in a special chapter on the Corfiotes (with another on the Smyrniotes) where he observes that Maltese connections, quite numerous in Corfu, Cephalonia and Zante for example, gradually penetrated mainstream Greek society and fully assimilated, without forgetting their origins. Maltezos is a leading solar heating brand while Maltezika and Gozzella are two well-known villages called after the Maltese Islands.

Maltese in North Africa

This targeted Eastern Mediterranean region however never managed to beat the vast Maltese community that had opted for Algeria, with Tunisia not far behind in numbers. North Africa had a number of advantages for early Maltese emigrants: the journey was very short and cheap; they could return without much hassle; il-Malti belonged to the same family of languages as Arabic and since most of the poor, who were leaving chattels and all, were peasants, agricultural activity in their destined land was accessible. The only surmountable challenge was religion, but evidence collected from official sources, showed that in North Africa the Maltese could easily mix and mingle with the native Muslim population easier than the Sicilians, the Spaniards or the French.

Among the myriad of families that Frendo enlists in his narratives, he notes those settlers' progeny who moved from French African colonies to France, where they used to receive their further education and progressed to lead a successful career. Illustrious among them were Victor Hugo scholar Fernand Gregh, the only Maltese ever to become a distinguished member of the Académie Française and Laurent Ropa, who together with later authors of Maltese origin, among them most prolific Pierre Dimech, left a mark in Franco-Maltese literature.

City with largest Maltese community in the world

While migration to Australia accelerated in the second half of last century, the Maltese sought refuge there as early as 1883. Pioneer Capuchin friar Ġakbu Cassar, who became the legend of the land, had led a group of 40 men to work in the cane fields in Queensland. For many Maltese and Gozitan migrants, decades of years ago, the Church appeared to be a reference point mostly for those who had hardly ever ventured outside their village and whose identity was narrowed to their parochial religiosity. The author posits that the Catholic Church helped such migrants "work out the meaning of life and experience, overawed as they were, by immense spaces, different races and value systems". This was quite evident at least until 1986 when in the Melbourne metropolitan area alone there were still weekend masses said in Maltese in at least a dozen churches. Migrant Maltese parishioners also set up village festas including il-Lunzjata, il-Madonna tas-Sokkors, San Ġorġ, San Ġużepp, San Pawl, l-Imnarja, San Lawrenz, San Gejtanu, Santa Marija, Santa Liena and San Pietru among many. Other cities, like New South Wales and Adelaide, had others of their own.

The author believes that more than 380,000 Maltese settled Down Under certainly creating the biggest Maltese community outside the Maltese Islands, with Melbourne counting over 56,000 in the year 2000, making it the city with the largest Maltese community in the world. All over the Oceanic continent, Maltese descendants, 140 years after the first migrants, must have reached or surpassed Malta's own current population by now.

Proud to be Maltese?

What intrigues the reader in this volume, besides vivid narration of challenging trips and difficult settlements, is the way Frendo delves deep into the socio-psychological transition of so many who faced an alien environment peopled by speakers of different tongues. Addressing the Convention of Leaders of Associations of Maltese Abroad and of Maltese Origins held in Valletta in 2000, the author reflects upon Maltese consciousness of emigrants who found themselves in new domains. Are the Maltese overseas proud of being Maltese? Some are and some are not, Frendo observes.

There were those who attempted to assimilate as fast as they could. The better educated, he explained, could even be half-ashamed of being Maltese because of a perceived "stereotype of the Maltese 'dago' (a denigratory term for southern Europeans common up to the 1950s) as short, dark and ignorant". For those who were groping for identity in their adopted lands cuisine was a part of Maltese identity. Yet the author did not come across one specialised Maltese restaurant in Australia where so many ethnic gastronomies vie to charm millions of immigrant patrons. Contrastingly, the Maltese folk-singing l-għana in Australia developed much more than in Malta, which should point to something missing in the heritage of these Islands.

In another engaging chapter on Down Under settlers, written in 1991, Frendo tackles racism as suffered by Maltese migrants at the hands of "Anglo-Saxon working classes, from the workers" unions and from Labour governments who had firmly upheld a "White Australia policy in which the Maltese had difficulty passing off as white". Though officially considered as "hardworking and honest" by a 1925 Royal Commission, Maltese immigrants were also branded as "mostly uneducated and their standard of living inferior to that of the British or Italian".

Emigration studies

Often throughout this volume Frendo could not help but don his academic hat with analytical opinions and suggestions on the dubious future of the Maltese language overseas, emigrants' connections with their original homeland and stronger recognition by the latter, and his wish to set up some cathedra for Maltese Studies in places such as Victoria or New South Wales. Back home in Malta with his family after 1988 however, he founded the Institute for Maltese Studies at the University of Malta, which he headed for 10 years and where emigration still finds its pride of place in topics of post-graduate courses. The Institute offers interdisciplinary academic studies and research on various aspects of Maltese culture and identity.

Diaspora deservedly stands out as the most extensive exploration of Maltese migration to date. The volume is divided in two parts; the longer one in English with a second part in Maltese addressing other emigration topics. The chapters within its hard covers are certainly bound to entice current and future university students to pursue some of the many tracks, which Frendo elicits in this oeuvre.