Walking around the streets of our capital city, one cannot help constantly coming across several reminders of food, almost around every corner.

No, I am not talking about the large number of restaurants that are to be found in Valletta, but memories of earlier times - granaries, such as those found in the area of Fort St. Elmo; the indoor market, which traces its origins to the Knights of St. John; the monument commemorating the victims of the Sette Giugno riots, which were primarily motivated by hunger and the exorbitant price of bread; the former Castellania, where Sir Temi Zammit discovered that unpasteurised milk was the source of undulant fever; and even a World War Two sign for a Victory Kitchen amongst many others.

Built by the Knights of St. John in the mid-16th century on the strategically located Mediterranean island of Malta, Valletta quickly became a very important and cosmopolitan harbour city and a perfect place through which foreign culinary practices and new exciting ingredients would have been able to enter the island.

And, through the influence and strong links that the multi-national Knights enjoyed with overseas regions, some things which we might tend to associate with more recent times were able to come into Malta relatively earlier when compared to other parts of Europe.

1. Coffee

One example of this is coffee, a drink with which Valletta has a very long connection. Although coffee really started to gain popularity in Europe around the mid-17th century, Malta’s connection to it seems to go back around a century earlier.

In fact, some believe that Malta was the very first European country where coffee was introduced, most probably through Turkish slaves, who prepared their traditional beverage in the prisons where they were kept.

A statement from a German traveller in the mid-1600s talks of this strange concoction of a powder resembling snuff tobacco, which the Turks mixed with water and sugar, and which they could sell to earn some extra money.

Soon the Knights themselves became very fond of this drink and would visit the Bagno degli Schiavi (Slaves’ Prison) because this was where the best quality coffee could be found.

This theory is of course quite plausible considering that the Ottomans at this time had full control over the coffee trade, and later introduced it to the rest of Europe through Venice, with whom they enjoyed very strong trade relations, but this does not totally exclude other possible ways how this product could have found its way into Malta at such an early stage.

Piracy cannot be excluded, as Maltese corsairs would have undoubtedly confiscated coffee grains, along with other cargo, during their continuous raids against Ottoman shipping, while it could also have first been offered to a Grand Master as a gift from some North African prince or bey, or it could have entered through other European merchants, most likely French, who traded with the Orient.

The Knights’ fondness for coffee soon led to its introduction in Maltese high society. Coffee started to be imported regularly, and its popularity was such that soon numerous coffee shops sprouted all around Valletta, making it easily available to people from all levels of society, and proving testament to the high demand for it.

The Grand Master even had a waiter employed as part of his magisterial household at the palace, known as the Garzone del Caffè, whose sole job was to prepare and serve him coffee!

According to a 17th century document found at the National Archives, for the perfect cup of coffee one needed coffee beans, a special coffee pot made of copper, and to know how to recite the Apostles’ Creed. Coffee, it was recommended, should be left to brew for as long as it took to recite this prayer.

Like today, coffee was normally served at the end of a meal, together with the dessert, often a piece of cake or other pastry.

Interestingly though, coffee was also believed to be a remedy for many ills.

A 17th century treatise about coffee, written in Malta by a certain Domenico Magri, claims that coffee was good for the lungs, the liver and the stomach amongst others, while, according to him, the Turks, who consumed copious amounts of this substance, never seemed to suffer from toothache, gout and other infirmities.

2. Chocolate

Malta was also among the pioneering countries to have introduced the drinking of chocolate in Europe.

Originating in Mexico, cocoa beans were probably introduced into our island by the Spanish knights. In the mid-1600s, a certain Francesco Buonamico wrote the Trattato della Cioccolata, claiming that “our island can truthfully boast of having been a forerunner in the coffee and chocolate drinking crazes that swept across Europe in the 17th century”.

Born in Valletta, Francesco Buonamico was by profession a medical doctor, but as was the custom for intellectuals at the time, he also specialised in other fields too: he was a botanist, antiquarian, linguist, scientist, poet, writer, theologian and enlightened traveller - best described as a post-Renaissance genius.

Buonamico wrote extensively and is best known for his travelogue, written over a decade that he spent visiting 69 cities all over Europe.

It was while studying in France, at the age of just 19, that he wrote what is considered as one of the earliest treatises on chocolate.

In this 8-page manuscript, Buonamico claimed that South American Indians resorted to chocolate drinking because they had no wine! This highlights the fact that at the time, chocolate was a drink.

The treatise provides us with a drinking chocolate recipe that included orange peel, spices, nuts and aniseed.

We also know that in Malta, cocoa beans were used as the principal ingredient for the preparation of a cold drink, a granita, a sorbet, and even an ice cream. By the late 1700s, chocolate wrapping paper started to be printed in Malta, indicating that by this point, chocolate had started to be consumed also as a solid.

Due to its expensive market value and exotic nature, chocolate was primarily consumed by the nobility, but despite its limited market, it continued to attract the attention of scientists interested in discussing its nutritional benefits.

Although not all of them agreed that it had any, it was still recognised as a precious treat, and there are various references where chocolate was offered to dignitaries visiting our island. Grand Master Pinto presented chocolate as a reward to a group of individuals who managed to infiltrate a network of organised smuggling from the Order’s bakery.

Grand Master de Rohan had a personal chocolatier who worked at the palace, while a number of Inquisitors of Malta are also known to have treated their high-ranking guests with this sophisticated drink.

In an inventory of the Inquisitor’s Palace compiled in 1798, no less than 3 copper chocolate pots, among other specialised equipment, are listed, with the sole purpose of satisfying the Inquisitor’s chocolate cravings.

3. Ice Cream

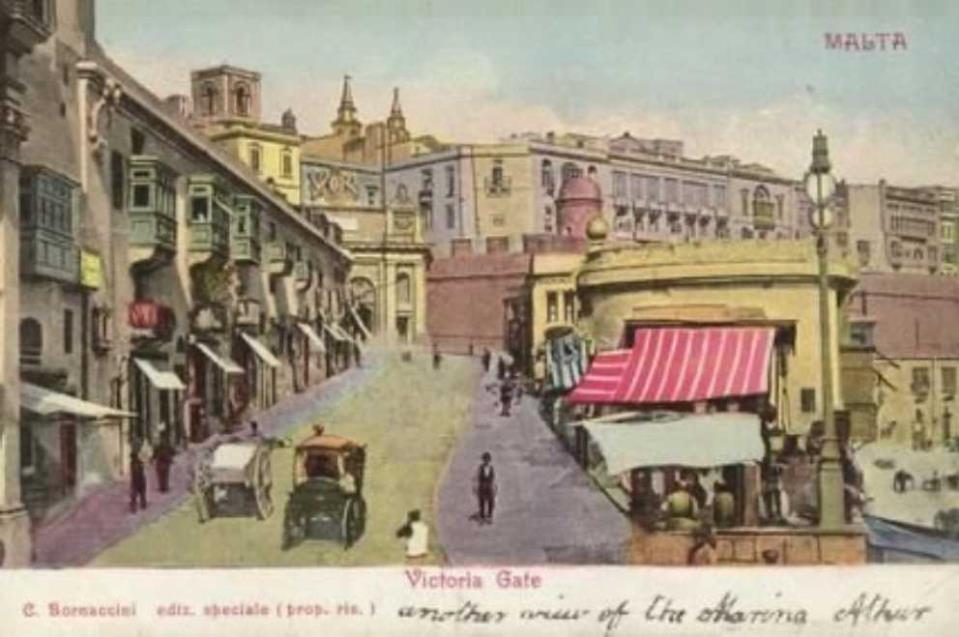

The area of Victoria Gate, which replaced the former Del Monte Gate, was once the busiest part of Valletta, being the main entrance into the city from the Grand Harbour area.

It has been described as Europe’s main entryway into Malta in past centuries and would once have bustled with activity, as loading and unloading of cargo would have taken place here, thus explaining the numerous warehouses and stores built in the area.

One of the people that once came ashore here was none other than Napoleon Bonaparte himself. This was of course just after the Knights had surrendered Malta to him.

The story goes that no sooner than Napoleon had landed, he was offered a serving of ice cream. Unfortunately, he refused it, as he apparently did not have time for the dessert, and wished to inspect the island’s fortifications instead.

Indeed, ice cream seems to have been a luxury offered to special guests at that time.

There is evidence that ice cream was very popular among the nobility in Malta already by the 17th century, with plenty of references by foreigners visiting our country, who were impressed with the common consumption of this dessert.

Probably its most important ingredient of course was ice.

The Knights had their very own ice caverns on the slopes of Mount Etna in nearby Sicily.

From there, the ice was compressed, packed in sacks, carried to the coast on mules, and lugged on to the Tartana della Neve (snow boat), which would bring it to Malta’s Grand Harbour.

From the shore, the ice would be taken to the ‘Snow Depot’ in East Street, just a little bit further up from today’s Victoria Gate.

A contractor was charged with supplying the ice all year round and had to pay a fine for every day he did not.

The ice was used instead of anaesthetic during surgeries, and to treat the fever of patients at the Knights’ hospital, but mostly it was used to make ice cream, sorbet, and chilled drinks, which offered the local nobility a moment of relief from the stifling heat of Maltese summers.

Malta also has what is considered to be the first and richest treatise on European ice cream, written in 1748 by a certain Michele Mercieca.

He says that milk was heated before sugar and egg yolks were added to it, as well as different flavours depending on the recipe.

This mixture was then poured into a specialised copper container, which was in turn placed in ice, in order to thicken and freeze the ice cream.

Mercieca claims that the presentation aspect was very important, with ice creams often made in the shape of fruits. Confectioners also made great use of dyes: cochineal was used to obtain a red tint, and saffron for yellow.

Pistachio gave the ice cream both the green colour as well as the flavour, while chocolate and coffee produced brown.

Incidentally, chocolate flavoured ice cream seems to have been the most popular, but Mercieca also lists a great variety of other flavours, some of which were very unusual, such as the recipe for Parmesan ice cream!

There is no doubt that the local availability of particular dishes and ingredients over time was influenced by Malta’s geography and history.

The island, positioned along important trade routes, has for centuries relied on importing most of its foodstuffs from overseas, and the various foreign powers left their mark on the local cuisine as they did on many other aspects of our culture.

This rich mixture makes for a very rich culinary identity that is certainly worth discovering.

In the past years, Heritage Malta has through Taste History and its multidisciplinary team of food historians, chefs and curators, been able to present to the public unique historic culinary experiences.

Heritage Malta’s Inquisitor’s Cookalong Sessions will resume on Thursday 27th May with a webinar focusing on honey in 17th and 18th century Malta.

This seventh cookalong session will go online and will start with a short feature about the history of honey in Malta, followed by the actual recipe and then an opportunity for participants to ask questions to a panel of experts: Dr. Noel Buttigieg, who lectures on the heritage and culture of food at the University of Malta; Mr Kenneth Cassar, Senior Curator for Ethnography and the Arts within Heritage Malta; and Chef Joseph Cassar, who will use an 18th century recipe to create Pan Papato, a sweet made with several luxurious ingredients for aristocratic tables, and possibly the precursor of today’s Christmas cake.

The cookalong session will be in English and starts at 7.00pm. Participants must register online beforehand.

In addition, the above food items are just some of the themes explored in Colour my Travel’s Valletta Food Tour, which offers a fascinating insight into the lesser known parts of Malta’s history and culture. For more information about our tours, visit www.colourmytravel.com

Matthew Camilleri is Tours Manager at Colour My Travel