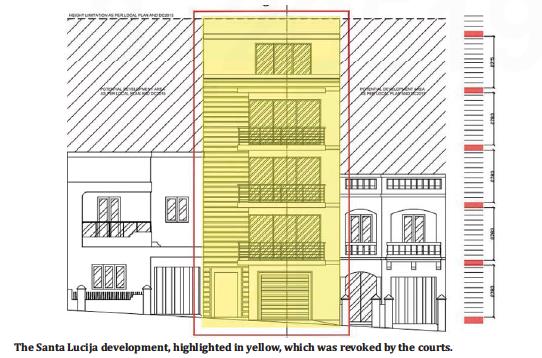

A landmark ruling has likely set a new precedent for pencil developments across the country, after an appeals court had revoked a planning permit, which would have seen a five-storey development rise amidst a street made up of two-storey houses.

The court, presided by Chief Justice Mark Chetcuti, this week had overturned a planning permit to build a five-storey building in a street characterised by two-storey terraced houses in

Santa Lucija – something which can be termed as a “pencil development.”

The term pencil development refers to situations where a streetscape is spoiled by a development which is much greater in height, which would have been approved owing to the fact that they do not exceed the maximum height which is allowed by Malta’s planning policies.

In the case of this development, the Planning Authority had turned down the application, but that decision was overturned by the Environment and Review Tribunal (EPRT) after the applicant – Charles Falzon – filed an appeal.

The PA had based its refusal on a section of planning legislations which state that in taking decisions, the PA should take into account “material considerations” which include things like legal commits and environmental aesthetics.

Furthermore, the PA based its refusal on the impact that the development would have had on the streetscape and skyline, being that when a uniform design prevails in an area then the emphasis should be on respecting these parameters.

The EPRT – which handles appeals on planning decisions – however had overturned the decision, stating that permits for buildings higher than two storeys had already been issued in the surrounding area.

This decision was challenged in the law courts by resident Michael Pule and PN local councillor and Santa Lucija minority leader Liam Sciberras, assisted by lawyer Claire Bonello.

In the sentence, Chief Justice Chetcuti said that the EPRT was mistaken in concluding that there were already permits in the same Home Ownership Scheme which had been granted with a height of over two storeys.

The court also found that the tribunal was “mistaken and contradictory” in its statement about the lack of applicability of the guidance policies in the DC2015 regulatory framework, when it was the tribunal itself which had judged the streetscape to be characterised by two-storey buildings which offer a sense of uniformity but had then judged the area to have no architectural value, even though this is not a requisite for the aforementioned guidance policies.

DC2015 is a set of guidelines approved in 2015 which include policies which oblige developers to respect the surrounding context of their development, but which had also included an annex which permitted the height limitation imposed in local plans to be interpreted in metres rather than in storeys. This meant that suddenly, fivestorey developments could be allowed in areas which previously had a three-floor limitation.

This has been applied inconsistently by the Planning Authority ever since, with pencil developments cropping up in what were previously uniform streetscapes all across the island.

The court also said that the EPRT’s decision went against policy, because it failed to take into account the representations of third parties and of the Superintendence of Cultural Heritage, and because it did not take into account the Strategic Plan for the Environment and Development

(SPED) either.

In its decision, the court said that “when there is a specific plan or policy for a particular zone, this should be respected.”

“However, when this policy is giving a clear direction on the height limitation, and this is satisifed by the proposed development, it doesn’t mean that there cannot be other policies regarding development which should be discarded and not considered”, the court said.

The court said that while the proposed development satisified the height limitation, it went against other policies which re

late to the impact on the skyline and design uniformity.

It observed that the EPRT judges the skyline to be compromised with buildings which rise higher than two-storeys, but failed to substantiate this assertion by showing specific permits which show such buildings in the area.

“An examination of the pictures show that the development is one of many sites facing an ODZ, in a street which is all twostoreys high”, the court said.

It said that the tribunal should not have ignored the “dominant defining design consideration”

which policy G3 in DC2015 states should be a part of the decisionmaking, and therefore should have taken into consideration the architecture of the surrounding buildings.

“The development, in conformity with the rest of the streetscape formed of two-storey buildings with a front garden, should have been done with a design of an architectural value which reflects two-storey buildings with a front garden”, the court said.

“As already stated, the height limitation in the local plan is a requisite to limit the maximum height, not whether the development is idoneous for the factual circumstances of the immediate zone where it is being proposed”, the court added.

It is for these reasons that the permit was therefore revoked.

The judgement sets a legal precedent for pencil developments, and gives legal certainty that the height limitations stated in the country’s local plans do not give developers an automatic right to build up to the maximum which that height limitation permits.

It will allow the Planning Authority legal certainty to take into consideration the context of other policies of specific areas, but could also pave the way to more objections to pencil developments which compromise existing and uniform streetscapes.

Santa Lucija local council minority leader and PN councillor Liam Sciberras – who fronted the case together with resident Michael Pule – took to social media to celebrate the court victory, saying that the decision meant the “protection of the Santa Lucija heritage” and that it will “not allow the greedy to rape the perfect environment of my birthplace.”

He also criticised the mayor and deputy mayor of Santa Lucija – Charmaine St John and Frederick Cutajar respectively – for their lack of cooperation in the appeal, saying that St John had “gone against the oath she swore when she was elected as mayor” as she chose to “defend the developer.”