My dear wife has been gently hinting I should not add more books to my overloaded libraries. I usually faithfully follow her wishes when they are in line with mine. But she was not surprised when she saw me engrossed in this new Bonello addendum. She knows I am a great fan of his and is painfully aware of my weak resistance to book allurement.

The last volume in Giovanni Bonello's 'Histories of Malta' series was published by Fondazzjoni Patrimonju Malti (FPM) in 2013. This prolific author's work needed to be further collated in more volumes, so this new series, freshly titled 'More Histories of Malta' was eagerly awaited. This new book named 'Falling in Eden. An anthology of stories of crime in Malta', naturally also published by FPM, contains 14 articles that have been separately published before but have now been revised and augmented.

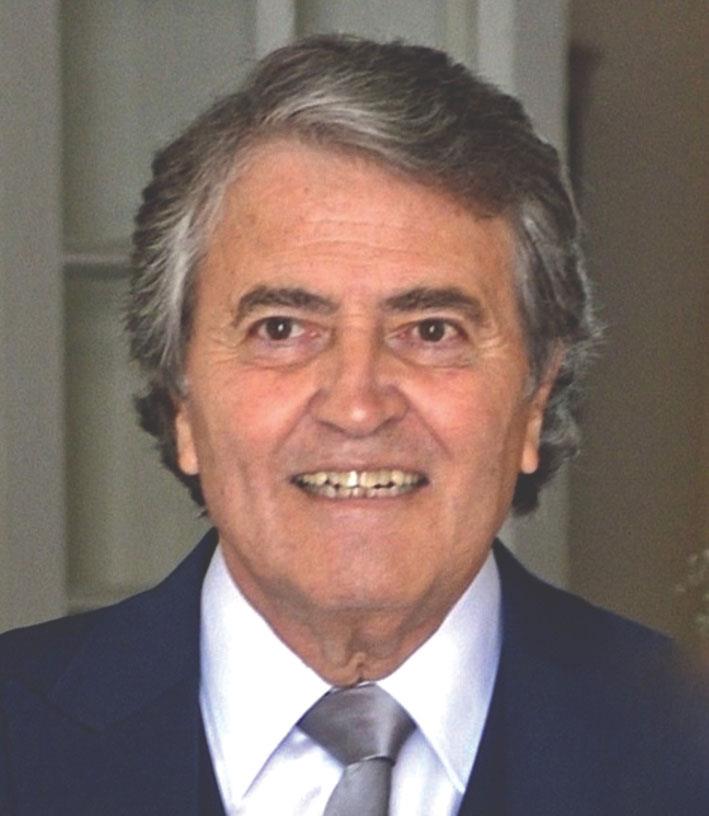

Giovanni Bonello, or as his friends know him, Vanni, is what I call a ground-zero historian in the sense that rather than hovering high for panoramic views, he glides low and offers a close-up approach to history based on documents which he unearths and relates in his typical manner that is both highly learned and informative, sometimes casual, occasionally tongue-in-cheek, but always enjoyable.

His writings contain a gold mine of information that sheds direct light on everyday life in Malta. The protagonists are knights, bishops, inquisitors, or ordinary lay people. The editor of this book, Gulia Privitelli, insightfully refers to Bonello's work as "feeding and shaping that microscopic narrative."

This publication deals with a good number of crimes committed on Malta, but, as the author warns, much information on crimes committed by or against the knights of Malta hits a brick wall. The Castellania dealt with criminal justice for the lay people. On the other hand, the Sguardio regulated crimes by or against the knights. These latter crimes were originally well documented whilst preserved within the Order's archives, but such records have since disappeared. All that remains are dry minutes of final deliberations by the adjudicating council. Alas, it's a collection of skimpy decisions! So, Vanni has a tough time giving flesh to details through his side-alley research.

A classic example is the crime committed on 12 July 1588 by Knight of Malta Fra Andrea de Ciambanin, who murdered the Maltese Nicola or Cola Borg. The entry in the official surviving records is short: guilty and condemned to five years imprisonment. By good luck, historian Joan Abela spotted a petition connected with this murder's investigation in a place utterly unrelated to the recording of crimes: the notarial archives. She showed it to Vanni, who connected it to the Ciambanin case. He sieved through this document like a Maltese Sherlock Holmes and concluded that the arrogant knight had provoked the poor Borg who was led to act in self-defence.

Why on earth should such information have ended in a completely different environment? I think that before leaving Malta in 1798, the knights had dispersed such damning material stealthily, and I suspect they managed to take with them a large chunk of documents recording criminal procedures - a remnant they wanted to conceal from everyone's eyes. Several knights could have shared these documents, including some hidden in the 78 trunks with personal effects and papers Grand Master Hompesch took with him when he left the island.

This author's extraordinary detective work on lawyers and lawyering in Malta before 1600 is commendable 'cum laude'. This was virgin land before Bonello insightfully spoiled that virginity. He searched high and low in publications by Fiorini and Wettinger and documents from the Universitas of Malta. Interesting is the use of the letters UJD or IUD following the names of some lawyers. These letters stand for 'Utriusque Juris Doctor', a doctorate in both Canon law and Civil Law. That is why today we still say doctor of laws, not doctor of law. I could not resist a chuckle when Vanni commented that he discards the IUD version "because they now refer to a contraceptive."

He offers an interesting list with short bios of 46 Maltese lawyers of the sixteenth century, including Dr Melchiorre Cagliares, who besides being the father of the only Maltese Bishop during the time of the Order, also enjoyed the luxury of three concurrent mistresses. Dr Giovanni Calava's name is historic since he is most likely the first Maltese lawyer to become a judge after the Order arrived in Malta in 1530. Insightfully, Vanni notes that this lawyer is reputed to have advised the Grand Master in his negotiations with Charles V to draft the deed of cession of Malta.

A terrible murder was committed in Birgu in 1636, where Nicolò Ciardi, a Sicilian, brutally killed his benefactor Francesco Scarletta to steal his belongings. Vanni informs us that murder was not a rare occurrence in those days. Every week, a knight killed or was killed. And this does not include crimes concerning non-Knights.

Once again, the details of this particular case are not found in an organised registry of the Order but have survived by pure chance in a 61-folio transcript, which was purposely left for safekeeping in the Notarial records. Why? Because the prosecutors wanted to justify their good faith by preserving and holding on to the evidence against the accused, especially when the Bishop's excommunication threatened these prosecutors. Ciardi had taken refuge in a Birgu church, and the civil police lured him out and detained him when he was crossing the harbour. The Bishop took great exception, and much wrangling followed. Still, the discussion was not about whether Ciardi was guilty but whether the luring stratagem contravened ecclesiastical immunity. Luckily, ecclesiastical immunity was abolished in 1828.

For me, even soiling books is almost a crime, let alone burning them. One riveting essay deals with the burning of books on 5 May 1609 in Birgu under orders of the Inquisitor Carbonesi. Included in the 52 books was 'De Humani Corporis Fabrica' by Andries van Wesel from Brussels, known more by his Latinised name Vesalius. Allow me to insert a personal addendum on this book. This book, written in Latin, was published in 1543 and 1555 and was the first major book of anatomy illustrations. Why should it have been censored by the Church? Initially, this book was not entirely forbidden; that is, it was not on the index of prohibited books, which was established in 1559. But the book was subject to what was called expurgation, that is part of it was censored. Since censors were spread across many countries and areas, the censoring varied. In one copy of this book, one would see the private part of the body covered. In another, just the printer's name, Optimus, was censured because he was a Protestant. This 1609 burning of books was a complete and drastic censorship. Surprisingly, in St John's Co-Cathedral, perhaps the only tombstone depicting an anatomically correct skeleton is an almost complete replica of one of Vesalius's engravings. This is the tombstone of Fra Stephane de Ricard, who died in 1716. I find it rather intriguing that one should include a drawing from a book included in the Church's index of prohibited books on a church burial slab. Was this a mere oversight? Or was it a change in the Church's outlook towards this book?

When dealing with various thefts from churches, Bonello includes a 1580 burglary of a solid gold basin with parts of St John's skull. The thief, Fra Vincenzo Pesaro, was apprehended and executed, whilst the basin which was returned to the Church was eventually looted by Bonaparte. Typically Bonellian, the author's remark attracts a smile from the reader: "Pesaro was executed, Bonaparte exalted."

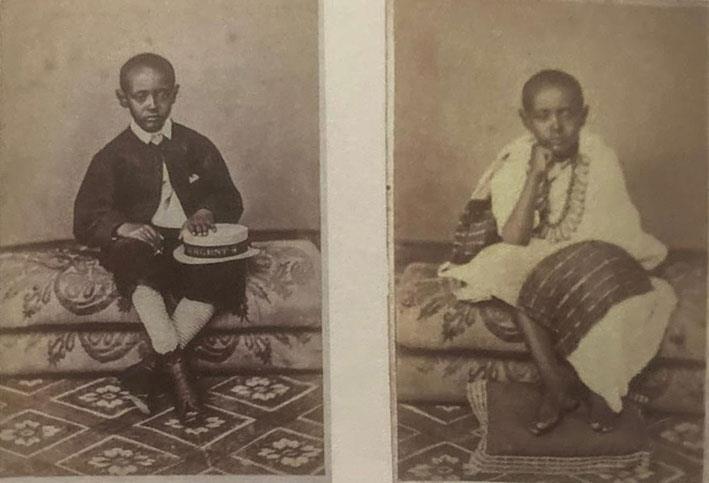

I was moved when I read the sad and tragic story of Prince Alamayou, son of Theodore II, Emperor of Abyssinia (now Ethiopia). The prince, who arrived in Malta on 25 June 1868, was photographed by Leandro Preziosi. He was a prisoner, ward, and guest of Queen Victoria, who wanted to have him educated in England, which was another way of Anglifying him. One cannot but feel saddened by the fate of Emperor Theodore, who sought to modernise his nation and requested a mission of British technicians to his country, which request was snubbed by the British. After overreacting to attract Queen Victoria's attention, the emperor was attacked by a force of 37,000 soldiers who conquered Abyssinia, thus leading to his suicide. The young prince left Malta on 4 July 1868 and, after dying in England at the tender age of 18, was buried in Windsor Castle. The Ethiopian government's request in 2007 to have the prince's remains repatriated was not acceded to. Any comment is superfluous.

After dealing with a series of proclamations, regulations and government notices issued during the early British rule, which impacted lawyers, Judge Bonello writes about the shameful behaviour of Malta's Crown Attorney General, Robert Langslow, who arrived in Malta in 1832 and shamelessly protected his son's criminal behaviour. Governor Bouverie strongly criticised him and even abolished the post of Crown Attorney General to make the office redundant. Langslow left Malta for Ceylon, where he worked as a judge and promptly made enemies galore. The Governor of Ceylon suspended him. Why the British authorities failed to inhibit this man from public office much earlier, completely beats me! Only the smell of a 'friendly club' can make sense.

The treatment of homophobia in pre-1850 Malta is a novel approach. Giovanni Bonello records the earliest mention of the 'crimen nefandum' in 1428. Notary Calava' had first confessed to sodomy but later petitioned the Viceroy of Sicily to expunge the sentence, alleging his confession was made under torture. His request must have been successful since he subsequently features quite often in Malta.

Sodomy was not only an unmentionable crime but was also unpardonable except by the highest authorities. After the Turkish razzia of 1488, an amnesty aiming at attracting residents back to Gozo specifically made an exception for those found guilty of sodomy. They were excluded from the amnesty.

This unmentionable crime was first considered a basis for expulsion from the Order of St John way back in the times of Grand Master Nicholas LORGNE (1277-1284). And everyone knows this sin was one of the major accusations and trumped-up charges laid against the Templars in 1306 leading to their complete eradication.

After the Knights' arrival in Malta, it did not take much time to encounter the first knight guilty of this misbehaviour. 1541 saw the conviction of Fra Serranus. Vanni sprays an abundant series of cases and surprisingly notes that "the overwhelming number of cases were Italians" even though they were not the most numerous in the Order. And when, in 1738, Dal Pozzo published his complete list of Italian knights, most of those guilty of sodomy were not even included.

I shall not emphasise Giacomo Capello's report of 1716, which is an exaggeration of everything anti-Order, but suffice it to mention that - according to him - a certain knight, Fra Oratio Zanzedonio from Siena, was nicknamed 'buco d'oro.'

One last piece of interesting information: in 1584, a Dominican from Haz-Zebbug, Padre Pasquale Vassallo, was tried by the Inquisitor for having sex with youths and writing poems in Maltese and Italian to various young lads from Mdina. He was found guilty and exiled from Malta. Sadly, the Inquisition ordered the destruction of all the poems. These would have been the second oldest poems in the Maltese language, after the verses of Caxaro. Yet, I would dread to think how accessible these would have been to all and sundry.

Giovanni Bonello accompanies us through the centuries, sprouting surprises, confirming prejudices, clearing cobwebs from the nooks and corners of dusty documents and many bigoted modern minds. He once again offers us history as it should be related, as an enjoyable experince.

I confess I missed Vanni's short, incisive poems which he sparsely includes in his other books. They are gems to be conserved and exhibited, not concealed for self-indulgence.

I shall remain perpetually grateful to this gentleman whom I admire on many fronts: for his courage to stand up and speak outright when only few did not fear to be counted, for his clear and erudite mind which he shares with great generosity, for his power over the word which he can use as a shower of knowledge, a sword and a source of smile.

I earnestly await the subsequent volume in this series.

ABOUT THE BOOK

Over a decade ago, Fondazzjoni Patrimonju Malti published the last volume of the widely sought-after Histories of Malta, a twelve-part series which overflows from the narrowest and darkest corners into the most iconic and unforgettable aspects of the Maltese Islands' history and heritage. With this new series, More Histories, former judge of the European Court of Human Rights, Giovanni Bonello, continues his mission to record and recount Malta's fascinating micro-history through six thematic volumes.

In the first volume of this new series, Bonello exposes some of Malta's grimmer and grimier stories. Selected and collated from his vast repertoire of history writing, here is an anthology of anecdotes that presents a potent mix of humanity, crime and creativity, illustrating some of the most haunting (and hopeful) questions concerning the human condition: Why do humans err? What is it that drives a human being over the edge, to think the unthinkable, to carry out the undoable, and to record the unsayable?

Credits

Creative Director - Michael Lowell

Design & Layout - Lisa Attard

Editor - Giulia Privitelli

Illustrations - Rebecca Bonaci

Publisher - Kite Group Ltd.

229 pages; soft cover; Euros 50

These volumes are being generously financially assisted by the Francis Miller Memorial Fund.