For those of you who are already familiar with the works of Rebecca Ranieri... well to put it bluntly, be prepared to have your minds blown away. Some of the familiar evocative anonymous faces, so much the signature style of Ranieri, are still present, but now we can even experience a transformation in the artworks. In fact, each artwork transforms thanks to the use of a light source. If the printed newspaper was like the newspaper in Harry Potter's world, I would have added some video clips accompanying this write-up to better show these works, but since we live in a less magical world (though Ranieri did manage to add some magic to it), I am providing before-and-after images of some of the works. All works were executed in Parma, where Ranieri resides, and come framed with a built-in light fixture, which enables this transformation at the touch of a button.

Throughout the history of art, light has played a crucial role, influencing various styles to varying degrees. For example, in chiaroscuro, light is often key, though its source is not always visible within the composition, as seen in Caravaggio's works. In contrast, artists like Georges de la Tour placed the light source, such as candles, at the heart of their scenes.

In more recent times, artists have begun incorporating actual light sources into their artworks, such as the illuminated pieces of Mel and Dorothy Tanner or the works of the Light Art movement, where light tubes dominate, like Stepan Ryabchenko's The Blessing Hand.

Ranieri's approach to light, however, is distinct. While light is an essential element, it serves as a tool for transformation - a trigger that shifts the emotions, age, and character of the figures she depicts, creating a profound "wow" effect. Her ability to achieve this effect is likely rooted in her background as a paper conservator, where she pushes the boundaries of paper as an artistic medium.

Since her first group exhibition in 2020, Ranieri has been experimenting with paper as a form of artistic expression. Her technique involves "deducting" material from the paper, beginning with simple scratches and evolving into the removal of entire sections. This process has developed into her own expressive language and a deep investigation into the potential of paper.

Ranieri places significant emphasis on the use of negative space surrounding the portraits in her works. With her classical training, she understands how, in the works of masters like Rembrandt, the background is often left dark and blank. In other cases, backgrounds serve to provide context or narrative, while some artists use ambient light to enhance their portraits. However, Rebecca plays with these traditional "rules" - in her works, the darkness becomes brightly illuminated, and ambient light turns into a stark, clinical white, drawing all attention to her portraits and the stories they hold within.

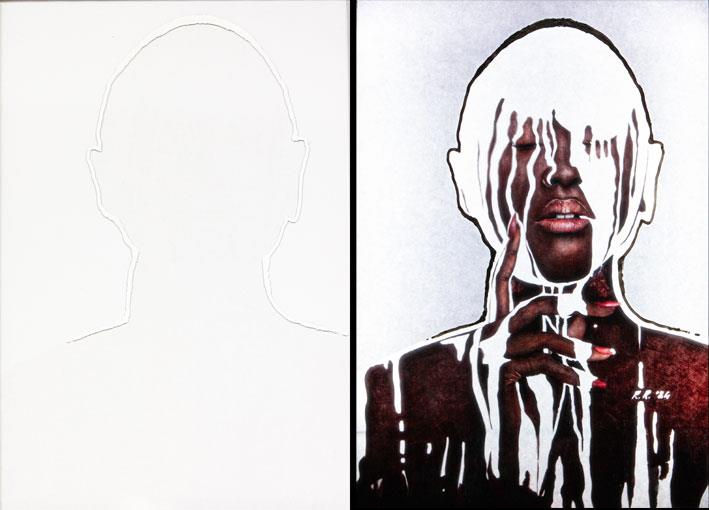

A particular example of how her use of light defies conventional expectations is seen in Undo. In natural light, only a white outline defining the silhouette of a head is visible, but once illuminated, the artwork transforms completely, revealing a dark outline and a hidden depth of what lies within, that was otherwise obscured.

Beyond their striking visual appeal, these works are deeply rooted in concept and research. Moksha, a central theme in Indian philosophy and religion, symbolises freedom and self-empowerment - freedom from ignorance, the realization of one's true nature, and liberation from the cycle of death and rebirth (samsara).

This concept lies at the heart of Ranieri's work, where she delves into the journey toward self-discovery and liberation. Through her distinctive technique, Ranieri captures the transformation of her characters, a metamorphosis revealed through embedded lighting. When illuminated, her pieces tell a story of personal growth, unveiling the hidden potential and true essence of each figure.

We, or I, love it when artists embrace experimentation for their exhibitions at our small but dynamic space. This time, we've decided to experiment with the exhibition layout as well. Our regular visitors to il-Kamra ta' Fuq will notice a significant change in our setup. While every exhibition brings a fresh arrangement, this one truly stands out. The room is dark, the rustic atmosphere has taken on a more industrial feel, and each cluster of works is connected by electrical cables to power extensions, almost like infants tied to their feeding source via their umbilical cords. With the help of electrical timers, we've created an installation where different works switch on and off alternately, generating a constant shift in the narrative of the pieces.

The works can be divided into distinct sub-sections. First, we have two striking portraits of women, whose faces, when illuminated, reveal the passage of over 30 years. Though still beautiful, the signs of time are unmistakable. This transformation might be seen as Ranieri's interpretation of Memento Mori, reminding us how fleeting time can be - changing in an instant, or at the touch of a button.

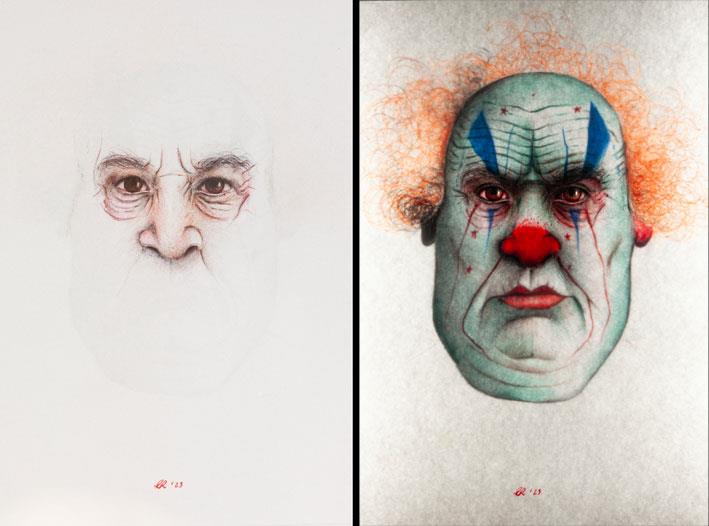

Another set features two male faces that transform into clowns when lit, though with a significant difference between them. In the piece titled Not a Dandy, a sad young man's face changes into that of a sorrowful clown, possibly hinting at an underlying narrative of someone forced to hide their true self.

The other clown evokes memories of IT - a movie I've never actually watched, but whose trailer on Italia Uno in the early 1990s haunted my nightmares. This piece bears the eerie title 17/03/1942 - Chicago. With its unsettling face and cryptic title, I was compelled to dig deeper. A quick Google search turned up nothing at first, but a more thorough investigation revealed that 17 March 1942, is the birthdate of the infamous American serial killer John Wayne Gacy, who was active in Chicago. To even confirm my hypothesis, I know that our dear sweet Rebecca's guilty pleasure is watching/listening to crime documentaries and podcasts. Case closed.

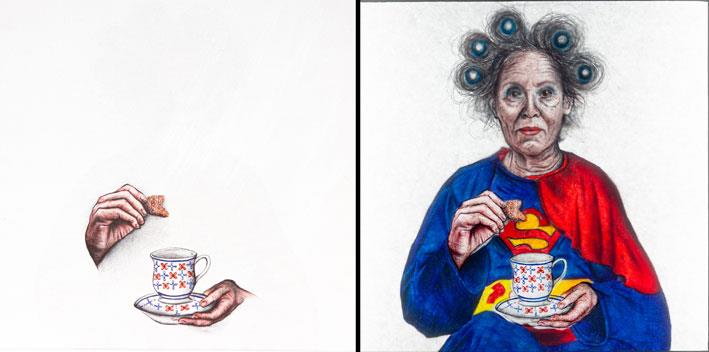

Switching to lighter topics, two of my personal favourites are SuperTea and Marie. The first depicts a pair of hands - one holding a patterned teacup and saucer, while the other proudly holds a cookie. When illuminated, an elderly lady emerges, dressed in a loose-fitting Superwoman costume, complete with a cape and a head full of hair rollers - it may be referring to superhero grandmas. Marie, equally vibrant, features a pair of stylish sunglasses, and when lit, reveals a fancy elderly woman dressed in her finest, showcasing her elegance and flair.

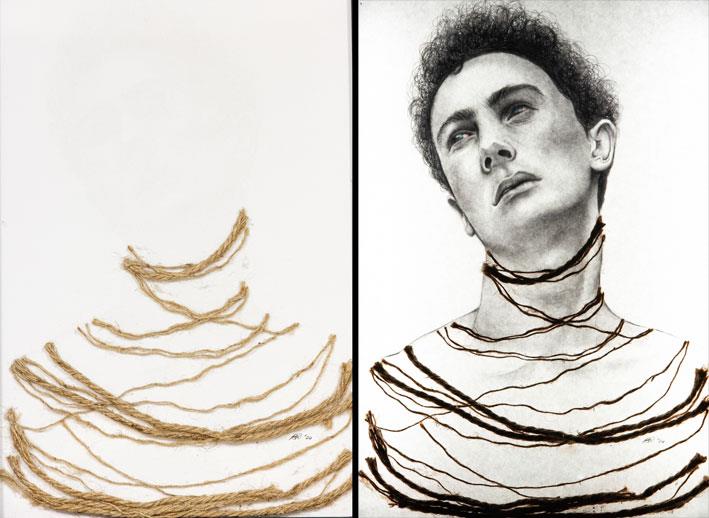

Two other noteworthy works are Sebastian and EXcuse. When unlit, these pieces display what appear to be props attached to the artwork's Perspex. In Sebastian, intricate ropes are shown, but when the light is switched on, you realize these ropes are holding a striking figure of Sebastian captive.

EXcuse, on the other hand, seems to address the issue of domestic violence. Initially, the piece presents a white veil over a white background, evoking a sense of purity and innocence. Once lit, however, the scene dramatically shifts to reveal a female face with smudged makeup, bruises, and a bloody lip, exposing the darker reality beneath the surface.

Ranieri has mastered a truly unique technique, one that gives voice to a diverse range of characters from all walks of life, bringing their stories to light in a remarkable way. To conclude, I'll borrow a quote from Roy T. Bennett: "To shine your brightest light is to be who you truly are."

Last but certainly not least, it's important to acknowledge and thank Rebecca's better half, artist and photographer Clint Scerri Harkins, whose expertise was instrumental in developing the technical aspects of the framing and presentation of these stunning works. Great teamwork!

The exhibition Moksha runs until 6 October at il-Kamra ta' Fuq, Mqabba. For more information, follow on social media.