It is now 60 years since Malta officially became an independent nation; ended the journey on one rocky road and started a new journey on another equally rocky road.

It's a story often told, but on this occasion, The Malta Independent on Sunday has dipped into the archives to tell the story through several items dating back to this period.

From a button badge to a religious holy picture; from a referendum ballot to a newspaper, and items from the private archives of well-known Maltese historian William Zammit offer a glimpse into some of the everyday items from this decidedly not everyday period in Maltese history.

The road to Independence was not easy. While both the Nationalist Party, led by George Borg Olivier, and the Malta Labour Party, led by Dom Mintoff, agreed that it was the way forward, the two political power houses disagreed on how it should be done.

The 1962 election was held based on this debate.

The PN wanted to attain independence and then join the Commonwealth while also maintaining close ties with Britain through the signing of a financial aid and defence treaty. It was also in favour of joining NATO and taking the side of the West in the Cold War that, at the time, was at its peak.

The MLP meanwhile wanted to first attain independence and then decide with whom to negotiate for aid and defence issues. It preferred to work on a system of neutrality as regards to international politics, rather than aligning with either side during the Cold War.

Mintoff and his party, however, had become embroiled in a social conflict that would come to be a defining factor in the eventual election. Archbishop Michael Gonzi was alarmed at Mintoff's close stance with Communist leaders and began to see that as a threat to the Catholic faith in Malta. Mintoff himself saw Gonzi as the biggest obstacle to the modernisation of Malta which, he believed, could only come through the secularisation and hence separation of the State from the Church.

Mintoff put forward his so-called sitt punti, which included the introduction of civil marriage and the removal of the Privilegum Fori. Both figures proceeded to paint each other in the most negative light possible with Mintoff depicting Gonzi as a British collaborator who was against Independence and Gonzi depicting Mintoff as an enemy of the faith. Things came to a head when on 8 April 1961, the Bishop gave a "personal interdict" on the entire Labour Party executive, making it a mortal sin to vote for the party.

The PN was elected to government in 1962 and could therefore move forward on the independence that it wanted to see, but concerns about this big step remained, even within the Church, which was concerned at the impact independence may have on its position.

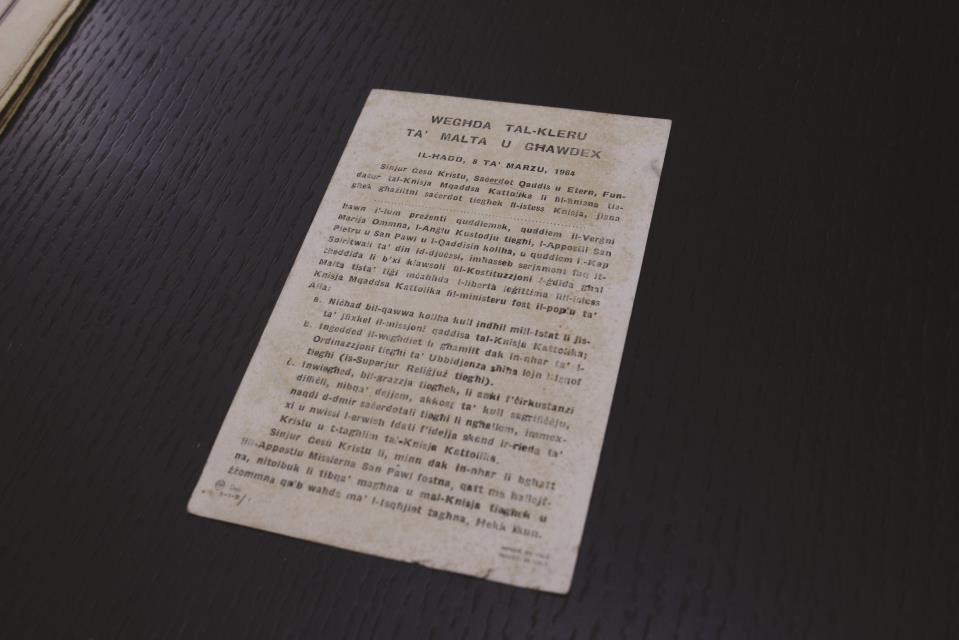

An artefact out of Zammit's archives that shows this in the plainest of forms: a religious holy picture - or a santa, as it's better known - with a promise by the Church on the back. It is dated 8 March 1964 and reads that the Church is "seriously worried about the threat that with certain clauses in the new Maltese Constitutions the legitimate liberty of the Holy Catholic Church may be breached".

It contains a guarantee of a denial of any interference from the State in the Church's mission and a promise that even in difficult circumstances, the follower will continue to spread Christ's message.

The back of a religious holy picture, issued by the Church in Malta in March 1964 amidst concerns that independence may lead to the Church losing power in Maltese society

Constitutional reform is without doubt one of the more complex matters to explain to the general public. But it was key for the Nationalist government to get the people on its side with what was being proposed.

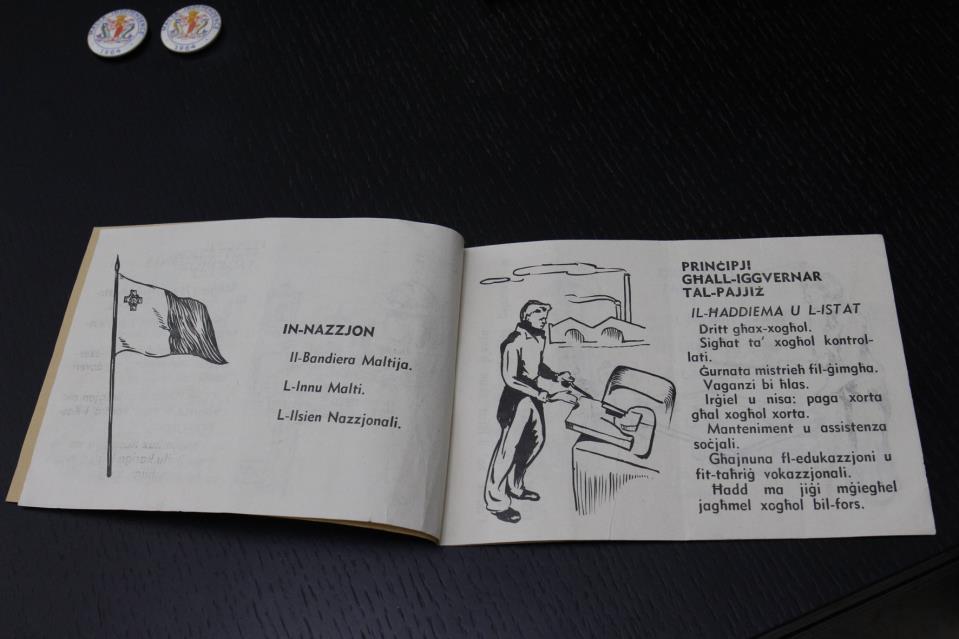

A key part of that was a booklet issued by the Department of Information and sent out to every household prior to the referendum on the proposed Independence Constitution.

This booklet summarised the key parts of the constitution into bite-sized chunks, with illustrations thrown in to drive the message home.

The first page was dedicated to sharing that Malta will remain part of the Commonwealth and that the Governor General will represent the Queen, and the second page ensured to stipulate the position the Church will have.

It detailed how Roman Catholicism would be the national religion, how religion would be taught in all government schools, and how the Church would be free to exercise its powers and spiritual duties.

Other pages explained various principles such as obligatory education, human rights, broadcasting, impartial law courts and a free parliament - which at the time was made up of 50 members (today, there are 79 MPs) - and elections.

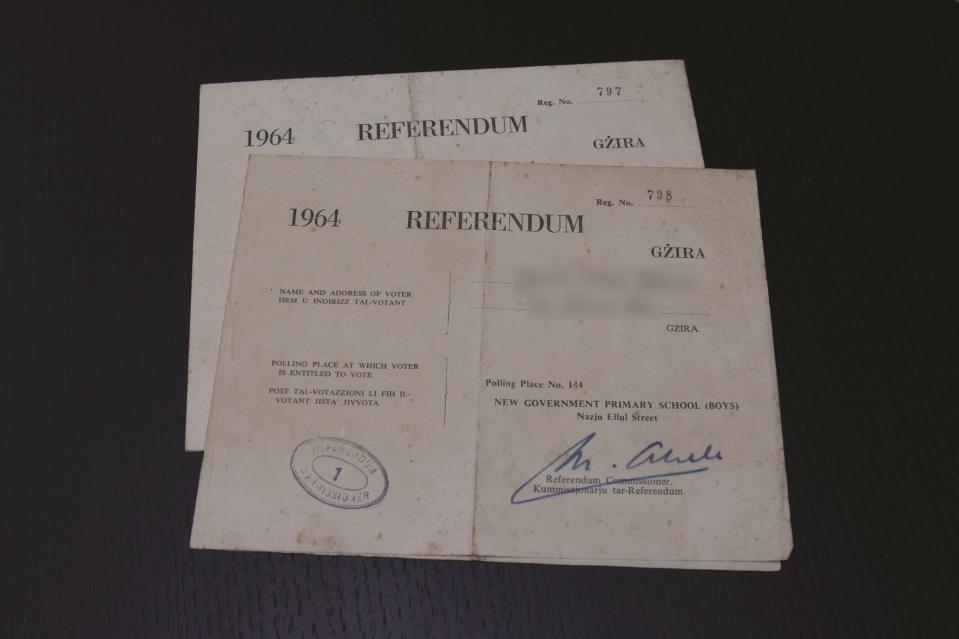

Two unused ballot sheets from the Independence Day referendum which took place in May 1964. Over 20,000 people abstained from voting on whether Malta should become independent or not

The referendum on the proposed Independence Constitution took place between 2 and 4 May 1964, and the electorate was asked to answer the question: "Do you approve of the Constitution proposed by the Government of Malta, endorsed by the Legislative Assembly, and published in the Malta Gazette?"

The Nationalist Party, which was in government, obviously called on voters to vote Yes, while the Labour Party called on its supporters to vote No.

The Christian Workers Party - Toni Pellegrini's offshoot from the Labour Party - which at the time had four seats in Parliament and Mabel Strickland's Progressive Constitutional Party asked the electorate to abstain from voting, while the Democratic Nationalist Party - Herbert Ganado's Nationalist Party breakaway - which had three seats in Parliament opted to call on supporters to invalidate their vote or leave it blank.

The idea behind abstentions or invalidations was to cast a doubt on the validity of the result, owing to a lack of representation. The PN had used similar tactics in 1956 when the topic of integration was put up for a referendum: while the PL backed integration, the PN did not - but the PN called on people to abstain rather than to vote No.

Out of a total electorate of 152,823, the number of people who cast their vote was 90,343 - 67,607 voting Yes, 20,177 voting No and 62,440 - equivalent to just over 40% of the electorate - did not vote. The PN argued that this was significant enough to show that the referendum was inconclusive.

There was no such notion in the case of the Independence Referendum though. A much more respectable 79.66% of the electorate cast their vote - equivalent to 129,649 people.

65,714 voted in favour, 54,919 voted against and 9,016 invalidated their vote. Still, there were 33,094 people who chose not to vote - and the two ballot sheets in Zammit's archive belong to two of those very people.

Pages from a booklet issued by the Department of Information in the run-up to the Independence referendum

But regardless of any abstentions, Independence Day came. Attended by the Duke of Edinburgh Prince Philip, the ceremony was based around what is now aptly known as the Independence Arena in Floriana.

The Prince handed over the constitutional instruments making Malta an independent nation to Prime Minister Borg Olivier, to the applause of many, in a ceremony which was attended by thousands.

With Independence, the Maltese government wanted to hit the ground with a clean slate, particularly when it came to national identity. Borg Olivier's government came up with a new national emblem, which incorporated both the George Cross and the eight-pointed cross in a heraldic image drawn up by the Royal College of Arms, based in London.

A Latin motto was settled upon, Virtute et Constantia, translating to Courage and Perseverance, which in itself has a long history. Grandmaster Jean de la Vallette used the phrase to describe the Order of St John's victory of the Great Siege of Malta in 1565, and that in turn is said to have inspired Antonio Sciortino in his concept for the Great Siege monument.

The new emblem featured heavily in items handed out to commemorate the occasion. One such item was a button badge, which was handed out to children who attended the celebrations, while it also featured souvenir programmes detailing the whole week of events.

The emblem itself was ditched in 1975 a little over six months after Malta became a Republic.

At a state banquet at the Phoenicia Hotel, which this year was replicated down to the most minute of details, the Prince told those present that as far as the Queen was concerned, Malta was unique in the sense that it was the only place outside of the British Isles in which she had lived rather than merely visited.

"In some parts of the world I daresay this occasion might be described as the liberation of Malta from the yoke of imperialist aggression. All I can say is that people, who are supposed to have been downtrodden by the British for some 160 years, have given me a very kindly and cheerful welcome yesterday and today," he said.

As midnight approached, the invitees and tens of thousands of members of the public looked on as the British flag was lowered by a member of the same Royal Sussex Regiment which had hoisted it for the first time over Malta 164 years prior, and the flag of independent Malta was raised in its stead.

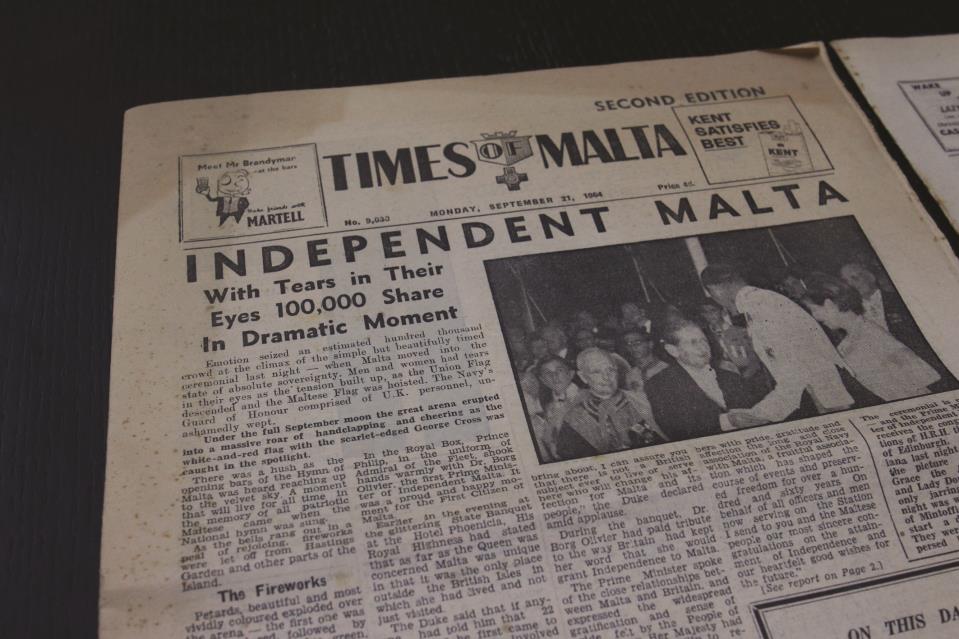

The Times of Malta on Independence Day itself reported how an estimated 100,000 people had partaken in the "simple but beautifully-timed" ceremony. It was the Times' second edition of the day - meaning that the media house published two distinct issues on the same day.

"Under the full September moon the great arena erupted into a massive round of handclapping and cheering as the white-and-red flag with the scarlet-edged George Cross was caught in the spotlight," the newspaper wrote in its front-page report on the ceremony.

"There was a hush as the opening bars of the Hymn of Malta was heard reaching up to the velvet sky. A moment that will live for all time in the memory of all patriotic Maltese who came when the National hymn was sung."