"Our meddling intellect

Mis-shapes the beauteous forms of things: -

We murder to dissect"

-Wordsworth (Tables Turned)

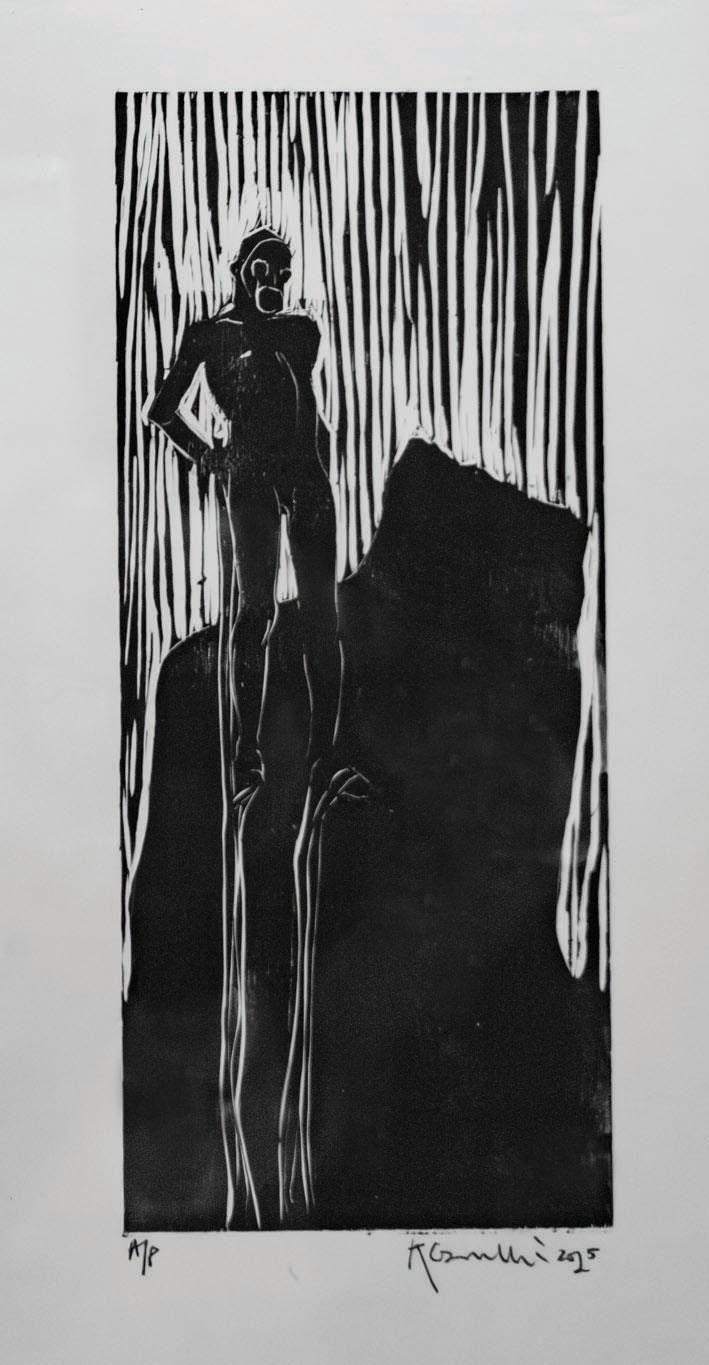

Reverberated echoes of Edvard Munch's scream and expressionistic contours mould the dystopian landscape as solitary figures trudge the threatening terrain. The once utopian dream of humanity's harmonious bond with nature is now turned into a ghoulish nightmare wherein "looms [William Ernest Henley's] horror of the shade." A poignant reminiscence expressed in Roderick Camilleri's new exhibition at MUŻA, titled 'Memoirs From The Future'.

Roaming through the exhibition of masterfully executed prints, visitors are greeted with figures that have no distinctive identity. Traversing various printing techniques, the artist offers glimpses into a futuristic ecological dystopia. Across the works one senses an ever-growing schism between nature and humanity. According to Giuseppe Schembri Bonaci's 'Not Art Only' essay, this very schism arguably stems from the fact that humanity is debating the status of its own existence, thus revealing its alienation from its own habitat. This separation from nature is portrayed by Camilleri through two important vectors: the gas mask and the stilts.

The first is the fact that the only scrap of clothing these eerie figures don is the gas mask that helps them to breathe. Playing on the aesthetics of Otto Dix and his 1924 etching Stormtroopers Advance under Gas, Camilleri homogenizes his figures through the skull-like mask which continues to add to the dystopian expressionistic idiom in the artist's aesthetics. The mask serves as a reminder that the breath once held sacred, has now turned fowl. Gaia; Mother Earth; Nature, silently turns against its own and as a result, to use Munch's own words "the flaming skies [hang] like blood and sword over" humanity. In Camilleri's woodblock prints the atmosphere is predatorially opposed to its inhabitants, raining glass-like shards onto the survivors. The air possesses a sharp lethalness to whomever breathes it in and thus, the habitat has now become inhabitable. In his etchings, the air seems as if it is transformed into fogs of ash obscuring the landscape from those who seek to navigate it.

The second aspect of the artist's works is the predominant use of stilts. The use of these elevation tools can be traced all the way back to ancient history where shepherds and farmers used stilts to cross muddy terrain and to also keep watch over their herd. In certain cultures, these devices were used for ritualistic purposes and in others, such as in ancient Rome, they were used for childish games. Stilts became popularised during the 18th and 19th century in conjunction with the rise of the Circus acts. Thus, they contain an almost farcical effect which is countered by the dexterity of the performer. This aspect debatably gives a tragic-comic effect to the stifled figures rising above the skyline. They are once again separated from the earth which bore them, sustaining the schism with nature. However, such dystopian outcomes paradoxically always arise from utopian aims. Unfortunately, several historical atrocities that were committed with utopian trajectories ended up with dystopian results. So, if this utopian aim can be the cause of dystopia, one begs the question; What is Utopia?

According to Margaret Atwood;

"'Utopia' is sometimes said to mean 'no place', from the Greek 'O Topia'; but others derive it from 'eu', as in 'eugenics', in which case it would mean 'healthy place' or 'good place'. [...] utopia is the good place that doesn't exist."

This concept of the good-healthy place of 'No-land', or to take a fairytale approach, 'Neverland', is slowly becoming a reality. On the one hand, we have the Orwellian nightmarish fear induced by Big Brother who through acute surveillance, monitors and controls society, demanding worship. This austere reality is seen in the story of Julian Assange, an Australian editor, publisher, and activist who founded WikiLeaks. Assange was incarcerated due to his diligent pursuit of truth and has only recently been freed. According to him "the world is not sliding, but galloping into a new transnational dystopia." However, this aspect of surveillance and censorship is not sustained through fear as Orwell had suggested, but from the Soma-induced pleasures of Huxley's 'Brave New World'. This dystopia is governed by a distancing from reality resulting in perpetual dream holidays to avoid confrontation with the self and with the fundamental issues of humanity. Paradoxically, the cause and antidote of this struggle stems from culture.

Culture cultivates an environment of nourishment allowing creativity and progress to germinate. Therefore, if one affects culture, one will alter various connecting factors. Aaron Timms, a reporter for The New Republic, states that stagnation has "spread to every corner of culture" due to our dependence on algorithms that have trapped users within a cycle of endless repetition. This never-ending loop is challenged in Camilleri's exhibition title and theme which paradoxically returns to the future yet to be in order to change the present. Algorithms are mechanistic loops which addictively feed but do not nourish, transforming the fabric of culture into an intellectual Neverland-playpen where society is trapped as a jittering nursling stubbornly refusing to grow up. One would hope that this one-dimensionality would be as intolerable as the nightmarish contours of Camilleri's desert landscape. However, it is doubtful whether we would be able to or indeed are able to give up our algorithmic pacifier and accept the difficult symptoms of change. Dostoevsky once stated, "The best way to keep a prisoner from escaping is to make sure he never knows he's in prison". Thus, one may argue that humanity is suffering from Stockholm syndrome; our problem may stem from the fact that we have fallen in love with our own incarceration.

Exhausted motifs and tropes have become continuously spread as innovative approaches due to their capacity to attract the court of public opinion. These approaches sustain a mono-cultural desert where we, as solitary figures clumsily move on stilts frightened to touch the earth from which we came and shall return. Technology, Culture and Nature are meticulously interlinked. As László Tarnay argues in 'Egology or Ecology?' the most disturbing issues are "the effect of our human environment and the predicament that digital technology rules our way more than ever." If, as the author suggests, "the route to ecological consciousness may be equally, or even more, viable through primary experience" then Camilleri's oxymoronic 'Memoirs From The Future' becomes even more poignantly relevant. His works can be interpreted as a vector jabbing at our ego-centric sensory experience with the futuristic ecological consequences of our present actions.

The artist brings to the fore several pressing contemporary issues which, if left unchecked, may lead to devastating results. By becoming conscious of our own destructive capabilities, we can start remedying the situation. Our personal internal psyche and our external environments have a mutual symbiotic relationship. Therefore, confronting a dystopia is both an internal and external struggle. For this, (I hope William Wordsworth can forgive me), I borrowed the romantic poet's sublime articulation on humanity's link with the environment and turned it on itself. Camilleri's work is a manifestation of psychomachia, a battle for the soul, one may even say a Dystopia "far more deeply interfused".

'Memoirs From The Future' is open at MUŻA until 20 April.