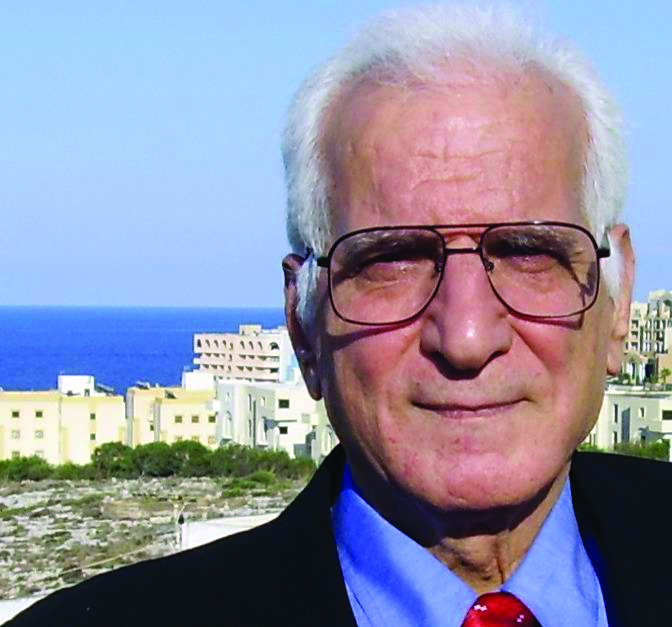

Adel Bishtawi born in Palestine, an experienced international journalist and novelist who is part of a pro-democratic writers association in Syria, gave some personal insight into the situation in Israel and the current evolution of the Arab Spring.

He has seen more than most would ever dream. Adel’s family fled to Lebanon and later to Syria in fear for their lives due to the massacre occurring during the 1948 Palestine war. This war resulted in the establishment of the state of Israel. Adel attended Syrian government schools as well as schools run by the United Nations, where his love of literature and his passion for writing flourished.

He then joined the Syrian News Agency, a state-run organisation and then moved on to become a spokesman for Syria, however, he fell out with the government following the attack Lebanon and resulting massacre. Fleeing to London, he met his future wife, Sue.

Many years later, along with a few friends, he founded a newspaper in England and, in 2002 chose to move to Malta, where his wife’s father also resides.

“I began reading very early on and a teacher at the UN school, gave me a copy of The Arabian Nights. I opened the book and began reading whilst walking home. Without realising, I looked up and saw my house, having walked five miles in an instant”.

Adel’s first novel has never been published. “I’m keeping it for myself, it’s special to me. When I write I don’t want people just to read, I want them to feel, to taste. I want them to smell the perfume on a woman, to see the sweat on a man’s brow, to truly feel like they are there”.

When Russia invaded Afghanistan

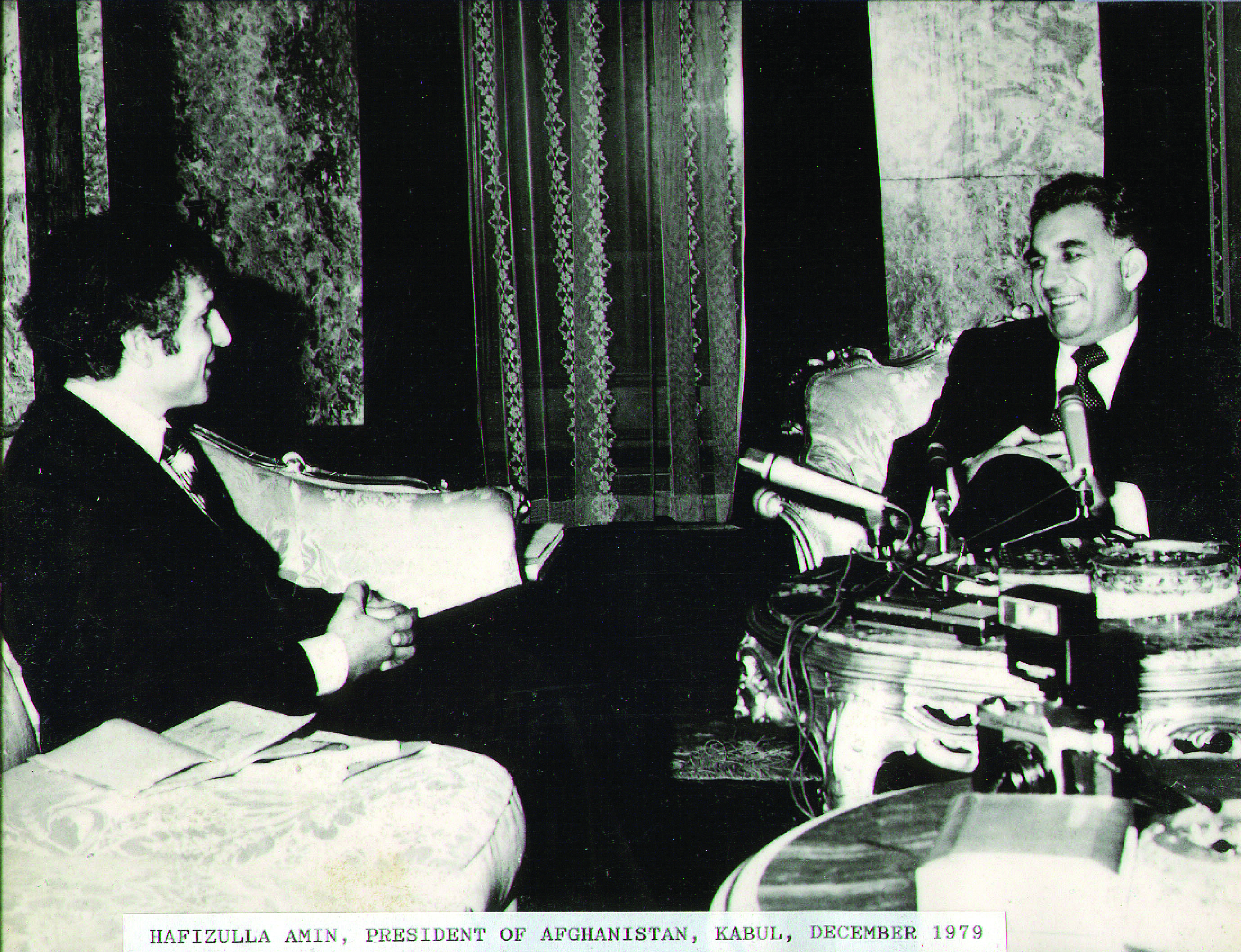

Adel was present during the Russian invasion of Afghanistan in 1979. Taking a sip from his cappuccino, he began to recount the events of that day.

“After a quick shower in my room at a hotel in Kabul, I took a walk through streets that looked bizarrely empty. Twenty minutes or so into my night stroll; nervous soldiers jumped out suddenly from screeching military vehicles and pointed their guns at me. With hands over my head, I tried to explain. Luckily, a lieutenant knew enough English to understand I wasn't told by the hotel receptionist about a total night curfew. I was driven back and ordered to remain in the hotel until further notice,” he said.

“A phone call by the receptionist early next morning made me nervous. As I walked out of the lift I saw the lieutenant with his soldiers. Nodding vaguely to things I said, he kept walking on and ordered me to get in his car. Driving past what looked like hurriedly erected military encampments and fast moving heavy military vehicles, I thought the drive could be my last,” he added.

“Outside a building at the end of what I knew later to be the presidential palace, I was met by a suited official who introduced himself as my translator. A few minutes later I was introduced to the President, Hafizullah Amin. It appeared that he was informed of my unintentional violation of curfew and was intrigued to know what the heck I was doing in tense Kabul. The interview was relaxed, as described by the British Sunday Times later, but those times were different. Survival and aggressive journalism did not go hand in hand with fast moving Russian tanks advancing towards Kabul”.

He was working for the newspaper Al Sharq Al Awsat, published both in London and Mecca, the President had said; “The Soviets supply my country with economic and military aid, but at the same time they respect our independence and our sovereignty and they do not interfere in our domestic affairs.”Within hours of making this statement, Moscow’s interference had proven to be total.

“Later that afternoon, I was asked by the receptionist to come down. An aide to the President had a large brown envelope. When he attempted to give me the envelope I stopped him and asked what was in it. ‘Tuhfa from the President,’ he said. Now, this word is originally Arabic, and has a number of meanings including 'a great gift'. I explained that journalists at my London newspaper are not permitted to take presents. The aide was confused and looked across to the reception at the entrance. The lieutenant came in. When the aide explained, he shook his head. He snatched the envelope and approached me briskly. ‘It is just a photo with the president,’ he hissed. ‘Take the damn thing and leave the county now’.”

“As I hurriedly brought down my suitcase, the hotel lobby was full of Russian soldiers. Waiting outside the hotel I stopped one taxi after another but all the drivers said the airport was closed. The next best thing I could do was to drive to the Pakistani border. Luckily, an Iranian taxi driver who had no idea of what was going on in Kabul agreed to drive me to the borders for a fee equivalent to what he could make in a month,” he added.

“At the border, an immigration officer told me I don't have an exit visa and I must go back to Kabul to obtain one. Nothing makes the mind work faster than fear. I took out the photo with the president and put on his disk. ‘The President,’ I lied, ‘Is my friend. If you don't want me to call him, please let me pass’.”

“It worked. Ten minutes later I was safe in Pakistan,” he concluded.

The next day, Hafizullah Amin and every member of his family were massacred, he said.

The Iron Lady

Adel had covered Margaret Thatcher for a number of years, and her constituency in north London was next to his so he attended a number of her local meetings. He remembers the events vividly.“Thatcher can be whatever people wanted to think of her. Was she an 'iron lady'? I don't think she was. Most people at the time judged Thatcher as a politician. After a number of 'relaxed' conversations, she clearly appeared to me a good mother and a good, but a slightly detached, wife. She was moved when I asked her about 'Thatcher the wife and mother', and she was mostly courteous and attentive but she could be abrupt and dismissive,” he said.

“Very few people dared criticise her decisions openly but she wasn't a political bulldozer. Despite her total objection to stepping down following some very unpopular decisions, the bull tax was one of them, the system triumphed and she was finally conquered”.

“I was outside 10 Downing Street when her successor, John Major, drove away in the Prime Minister's car. The curtain of the second floor window suddenly parted, and Thatcher looked down anxiously as Major disappeared into the darkness. Discreetly, she reached for her right eye and wiped a tear”.

“Undoubtedly, the financial theory she embraced full-heartedly proved disastrous. Probably, she is partly to blame for the financial collapse of 2008. Monetarism was a model that suited the USA, because it was based on the US Dollar, but not England or Europe. It relied partially on surplus oil revenues of the rich Gulf States that were lent to Latin American countries. It could be argued that Thatcher may have seen the future de-industrialization of the West as inevitable. The shift to consumer economy made sense but the people didn't understand it, and they were not ready for it,” he added.

“When oil prices collapsed and the oil revenues dried, financing the huge lending programs became a problem. Ronald Reagan, Thatcher's closest political friend and ally, started a borrowing spree that never stopped since. Financial engineering produced very exotic investments that proved worthless. The bubble had to burst. The remedy, so far, has been more borrowing and more money printing. That's where we are now”.

The US invasion of Iraq changed everything

Adel used to focus on love and romance novels until “the US invasion of Iraq. There was too much killing, too many problems. I didn’t feel proper writing about love when so many families were being killed. Love always survives you know… That’s when I began to look at the problems faced by the Middle East and began to write books based on history, the history of the Arab injustice, the American injustice and then I dove into a trilogy, called the book of origins”.

Following the beginning of the revolution in Syria, we formed a democratic organisation for writers called the Syrian Writers Association. Once we found independent financial backing, we organised a conference in Egypt. It is the first democratic entity in Syria. “We have our own magazine, website and a prize competition. The last one was held a few months ago in Turkey and the writers of the three novels who won were all still in Syria. We are trying to help as much as possible with the dissemination of news from Syria and literature. We are a civilian organisation”.

Given his vast experience in the Middle East both as a citizen as well as a journalist, Adel has some rather interesting insight into the situation in Israel.

“We really need to understand what the conflict is about. The conflict between Israel and Palestine is not about religion, and people need to understand this. The problem surrounds land so it cannot be solved. Both people have claims on the same land. One biblical, the other residential. Unless this problem is solved, I cannot see peace. It’s not about one side being Arab, the other Jewish, its not about different cultures. The new generations of Israelis and Palestinians are seeing the same thing so unless the land becomes a negotiable issue then the problems will remain”.

Freedom of the press in the Arab world can be a rather questionable topic. Every Arab country has different unspoken rules, Adel explained. In Morocco for example, due to a dispute with Algeria over control of the Sahara desert, one cannot say anything contrasting Morocco’s claim to the land. In Saudi Arabia, the royal family cannot be involved in any news stories and in the gulf one cannot be vocal against the government. It depends on what you write and how you write it. There are different levels of censorship, for example one level sees journalist self-censorship, another affects sensitive issues, such as religion and morality.

The US intervention in the Iraq, which has been a focus on one of his books, led to the Arab Spring, he said. “Saddam Hussein was the biggest strong man in the Middle East. He didn’t fear anyone, he could kill whoever he wants. The Americans did the Arabs a favour by removing Saddam Hussein, albeit having done so for the wrong reasons. So the fear that was built up, mostly based on illusions, dissipated. The end of fear in the Middle East initiated a very slow movement that was to become something different. It started with Tunisia and it was not originally meant to be a revolution. I believe this is only the beginning. Unfortunately people did not really appreciate the cultural revolution that took place back then. Normally revolutions in the region targeted foreign powers however this is different. The big thing about it is that the call for freedom and democracy is there, but the problem is that the people living there have nowhere to go whilst the fighting escalates.

The Arab Spring was just the beginning

Democracy holds a special place in Adel’s heart, a heart that yearns for the freedom from oppression for the Arab states. As a man who has travelled the Middle East and experienced life in the West, Adel, holds a certain perspective perhaps not many would be able to share. “I wrote a book in 2005 called the history of injustice, and I had foreseen the Arab world transforming. instead of accepting what the people wanted, Assad, in Syria, tried to oust them. He believes he has a right to be there and the people who don’t like it can leave. Change has to come. When looking at the situation in the Arab world, on must look at five countries. Morocco, Pakistan, Syria, Iraq and Egypt. These countries all became dictatorships at the same time and became democracies simultaneously. The problem in the Middle East is not that people don’t want democracies; it’s that some people don’t want change. I believe that in 15 years, countries in the Middle East will finally become democracies, I truly believe it”.

No place for undemocratic societies

When discussing the Middle East, one must mention ISIS, an extremist organisation currently operating in Syria and Iraq, attempting to create a Caliphate.

Adel believes that certain individuals from the Gulf States are trying to infiltrate their neighbours' world in order to halt the expanding democratic flame. “I think this is wrong. I think these people receive a lot of money from private individuals and not governments. If you look at the nature of people in the affected countries, most are students and have no idea who they work for. This association, this group, have money and weapons. Lots of people are out of work and blame the government for ignoring them. Syria itself is not a religious entity, and a religious government would not work now. If you look at who's behind these people, it’s the tribes. Iraq is an extension of what’s happening in Syria. It really started in Falluja. In 1982 the Syrian government had massacred people in the city of Hama, Syria and most of the people fled to Falluja in Iraq. In revolutions you need to expect extremism, but will extremism last… I don’t believe so”.