In an interview with The Malta Independent, Foreign Minister George Vella called for a review of the country’s military defence provisions to address new threats that have emerged in recent years.

He expressed particular concerns about the Islamic State (IS), an organisation which presently controls parts of Iraq and Syria and whose brutal methods have even earned it rebukes from al-Qaeda, which it was formerly affiliated to.

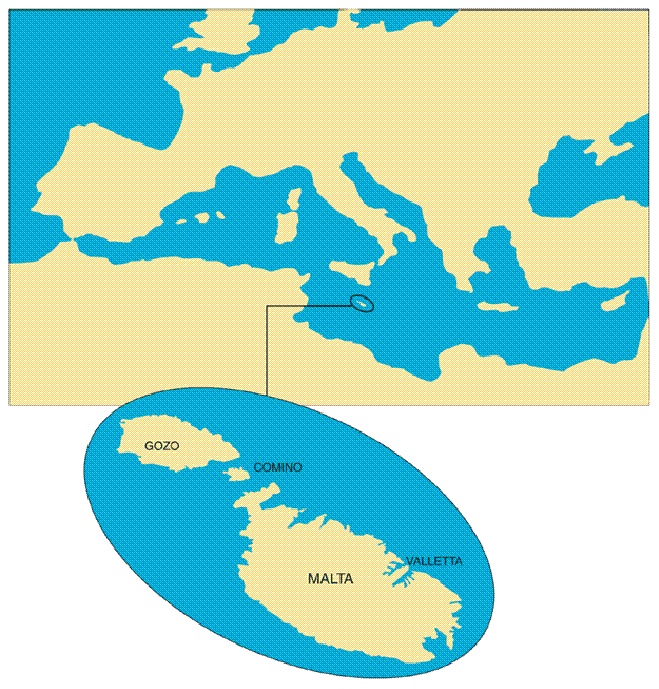

The group is believed to be seeking to infiltrate other countries, and Dr Vella expressed concern that it could establish a presence in Libya, with potential implications for neighbouring Malta.

But an analysis of the situation suggests that the risk of IS – or any similar militant organisation – infiltrating Malta is very low, verging on the non-existent, unless a particularly significant development occurs.

In any case, however, this has little to do with Maltese neutrality, but due to a more simple reason: a militant organisation with limited human and economic resources would seek to make better use of them elsewhere.

Can Islamic State sustain itself?

IS started out as an al-Qaeda affiliated group which was established in 2004, which was commonly known as al-Qaeda in Iraq. But the group gained considerable strength as it expanded into neighbouring Syria in the wake of the country’s civil war, and declared itself the Islamic State of Iraq and ash-Sham (ISIS) in 2013.

Last June, after making considerable gains in Iraqi territory, the group declared itself to be a Caliphate, formally changing its name to IS to emphasise its wider territorial ambitions.

In contrast to al-Qaeda, which it cut ties with this year, IS has effectively developed a proto-state, going beyond simply carrying out terrorist attacks into more conventional military operations – including taking over cities with thousands of troops. They have even seized control of Iraq’s second largest city Mosul, with a population of some 1.8 million people.

But its bold expansion has now led the US to carry out airstrikes in a bid to help Iraq and the autonomous region of Iraqi Kurdistan recapture lost territory, and there are indications that this assistance is starting to have effect.

Most of the airstrikes carried out so far have been in the vicinity of Mosul Dam, Iraq’s largest dam, which was captured by IS on 7 August: they have helped Iraqi and Kurdish troops retake control of the dam this week.

Retaking Mosul itself would prove to be a considerably greater challenge, but ultimately, IS’ resources – human and financial alike – are limited, and the group may have over-stretched them, more so now that its actions have led to foreign intervention.

Should the organisation somehow continue growing in spite of the present intervention, one could only expect other countries – particularly NATO members – to intervene. These members may ultimately include Turkey, which borders both Iraq and Syria.

The risk of terrorist infiltration

The group is known to be actively involved in recruiting volunteers from overseas, a process which is leading to it establishing a presence – however small it may be – in other countries. Such an infiltration, it appears, concerns the Maltese government, especially since unrest in neighbouring Libya appears to provide an opportunity for such an organisation to establish a presence.

But by all appearances, it makes little sense for a terrorist organisation with limited resources to seek to infiltrate Malta, particularly since larger countries would not only provide them with a greater potential pool of volunteers but would also make it easier for such operations to remain hidden.

After all, only a small proportion of people would consider abandoning a life of relative comfort to join a militant group which engages in brutal acts, and which is already attracting the attention of foreign militaries which may bring its downfall.

Malta only hosts a few thousand Muslims, including a sizeable proportion of Somalis who actually fled Islamic extremists in their native land, and who are unlikely to be attracted to such extremism elsewhere.

And the country’s lone mosque can hardly be perceived as a hotbed of extremism – the head of the affiliated Mariam al-Batool school, Maria Camilleri, is Catholic, and its imam, Mohammed el Sadi, readily condemns terrorist acts carried out in the name of Islam.

Another possible risk presented by IS and related groups is that of terrorist attacks, but even then, terrorist organisations are likely to find other targets a far more appealing proposition than tiny Malta.

It is unlikely, however, that Maltese neutrality would have any impact on terrorist groups’ considerations.

An outright invasion of Malta could be considered to be unthinkable; and it is certain that NATO, at the very least, would intervene if any EU member is invaded, whatever defence arrangements may officially exist.

The Maltese Constitution’s neutrality provisions would still be respected in such a case: the government is authorised invite foreign military forces if any “armed violation” occurs in its area.

The state of neutrality

Neutrality was entrenched in the Constitution of Malta in 1987: the Labour government of the time had insisted on its inclusion along with the electoral reforms sought by the Nationalist Party in opposition.

Since then, Article 1(3) of the Constitution states that “Malta is a neutral state actively pursuing peace, security and social progress among all nations by adhering to a policy of non-alignment and refusing to participate in any military alliance.”

Most EU member states – 22 of 28 to be exact – are members of NATO, a military alliance whose members commit to consider an armed attack against one of them to be an armed attack against the entire alliance.

Five of the six non-NATO members – Austria, Finland, Ireland, Malta and Sweden – follow a policy of neutrality, but all five are members of NATO’s Partnership for Peace programme. The programme’s stated aim is to build trust between NATO and other states in Europe and in the former Soviet Union, and save for a few small states, all non-NATO members in the region – including Russia – form part of it.

The only EU member who is neither a member of NATO nor of the PfP is Cyprus, but not for reasons of neutrality: Cypriot involvement in NATO institutions is being vetoed by Turkey in light of the dispute which has left the island divided along linguistic lines for the past four decades.

Neutrality may be perceived to be a way to ensure that a country is free of military threats, but its limitations have been made clear on a number of occasions.

The two world wars, perhaps, are the most notable example of how strategic considerations often trump respect of another country’s neutrality.

During the First World War, Germany invaded neutral Belgium and Luxembourg, mainly in a bid to skirt fortifications on the Franco-German border. The two countries were once more invaded by Germany in World War II, along with fellow European neutrals Denmark, Norway and the Netherlands: all five countries ditched their neutrality and became founding members of NATO in 1949.

The Soviet Union, meanwhile, invaded and annexed neutral Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, who had been a part of the Russian Empire until World War I. All three joined NATO in 2004.

As part of the British Empire, Malta could not have been neutral during the world wars, a fact which was decried in Maltese rock opera Gensna, in which a song’s refrain goes “we died in vain, we died for the foreigner.”

However, given the experience of other countries, it is hard to imagine that any hypothetical Maltese neutrality would have been respected by Fascist Italy – which had irredentist claims on Malta – or Nazi Germany, given the island’s strategic location.

Odds are that even the Allies would also have also sought to intervene, if only to prevent the Axis from gaining control: the UK had in fact occupied neutral Iceland in 1940 after Denmark – which handled Icelandic foreign policy at the time – was invaded. Iceland also became a founding member of NATO, even though the country has no armed forces.

Is neutrality still relevant?

Nevertheless, the Cold War that ensued may have given neutrality and non-alignment a greater value. In fact, both Finland and Austria, located between NATO and the Soviet Union-led Warsaw Bloc, adopted neutrality to stave off possible Soviet occupation. After World War II, Austria had been divided into four occupation zones as Germany had been, and its assurance of permanent neutrality ensured that it was not divided as Germany was.

The Non-Aligned Movement, whose members pledged not to align themselves with or against any major power bloc but are not required to be otherwise neutral, has attracted over 100 countries: Malta was itself a member until it joined the EU in 2004.

But since the end of the Cold War, the global situation is no longer dominated by two major power blocs at loggerheads, and the concept of neutrality may no longer be as relevant as it was then.

Arguably, EU membership does impinge on neutrality: all member states have agreed to a Common Foreign Security Policy, although Ireland has sought and received assurances that its neutrality would be respected. In a speech made at the European Parliament, former Finnish Prime Minister Matti Vanhanen had corrected an MEP who described his country as neutral by pointing out that “now we are a member of the Union, part of this community of values, which has a common policy and, moreover, a common foreign policy.”

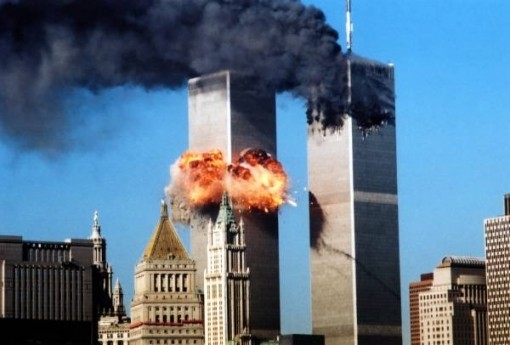

The September 11 attacks in 2001, in which al-Qaeda terrorists hijacked four passenger airlines to crash them into buildings – two hit the Twin Towers in New York City, another hit the Pentagon, and another crashed into a field after passengers apparently tried to overcome the hijackers – provided a horrific example of the changing global situation.

But the emergence of the IS provides a new development. The organisation has effectively managed to achieve what al-Qaeda has failed to do: establish a proto-state, whilst sharing its aim of establishing control over a vast region of what it perceives to be Muslim territory – a definition that includes, among other regions, Cyprus and Israel.

It is unlikely, of course, that organisations who are openly flouting international law and disregarding fundamental human rights would respect a state’s declaration of neutrality. Malta’s small size and relative insignificance in world affairs, however, is likely to lead them to seek greener pastures.