Dr John Hennen, an army doctor of Irish birth, came to Malta in 1821, as head of the Medical Military Department in the Mediterranean. During his three-year stay, he conducted a detailed study of the medical topography of the island. Topographical medicine, a science that was already in vogue at the time, examines how people's health is affected by their environment, especially as a result of natural conditions that augment endemic diseases and other afflictions. Dr Hennen investigated these in connection with the Maltese population at large as well as the British troops garrisoned here.

Dr Hennen's opus, Sketches of the Medical Topography of the Mediterranean - comprising an account of Gibraltar, the Ionian islands and Malta, was edited and published posthumously by his son in 1830. Hereunder is an account of the more salient points of his report. The article bears a few comments of my own marked in brackets.

Population and childbirth

Dr Hennen provided an overview of the general aspects of the population of Malta and Gozo that hovered around 110,000 of whom some 12,000 lived on Gozo. The Maltese married early and there were not uncommon instances when girls became mothers at the age of 13. Childbirths were in the main normal, although some suffered from uterine haemorrhage during the last four or three weeks of pregnancy. Newborns were swathed in clothing "as if they were Egyptian mummies", but this custom did not leave any adverse effect on the child. Dr Hennen noted that deformities were rare, although he claimed he knew of two cases in hospital of twin deformities, one pair joined by the back while the other pair was joined by the belly. The birth of twins was a common occurrence. He could not find anything adverse related to hereditary diseases.

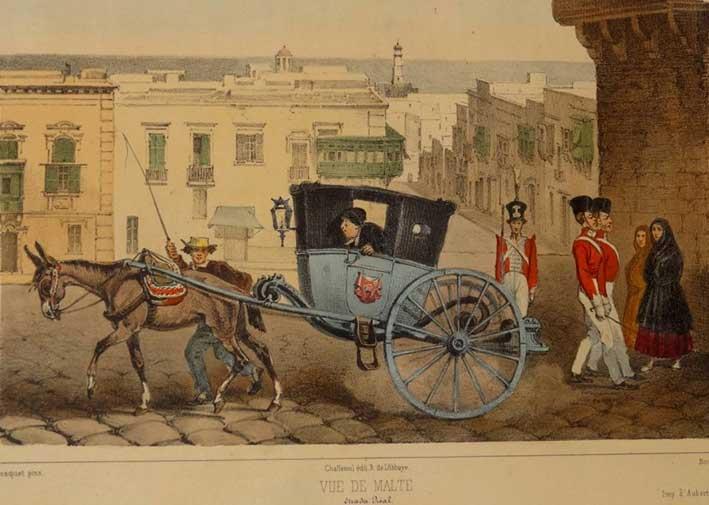

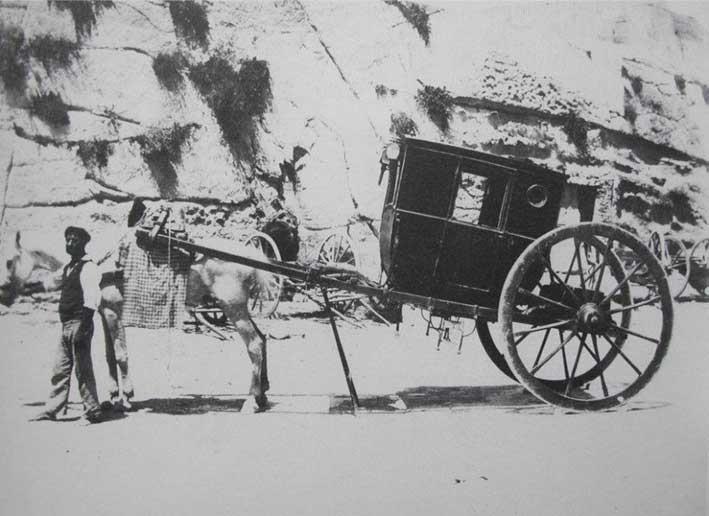

Of all the labour force, he believed that the healthiest and most robust were those working at the salt pans. The worst were the calessieros [calesse drivers] who, although "robust", worked extremely long hours, [incidentally, the calesse offered no seating accommodation for the driver and thus he was obliged to trot alongside the horse, often barefoot]. Such hardy conditions, Dr Hennen says, were conducive to an unhealthy and shorter life span.

The environment

Dr Hennen maintained that although the climate was generally healthy, there was a prevalence of very fine dust in the air driven by winds from Africa for six months of the year. He surmised that this "impalpable dust" especially in the summer months was "injurious to the eyes and lungs". In the winter months, Maltese people were particularly wary of "strokes of winds rushing through the streets" and these were blamed for the frequent pulmonic afflictions. Clothing and bedding did not protect the peasants from the damp air.

Dwellings in the towns were of the most superior order as they were lofty with plenty of doors, windows and balconies, thus generally providing good ventilation. Water was retained in cisterns in a clean state. Sometimes, however, sewer water filtered through and when this happened several bucketfuls of lime were needed to clean it of its impurities. Hennen proposed that live eels should be thrown into the cisterns to clear the water from infusoria [organisms emitted from vegetal material]. Houses had water drains that were connected to sewers which were kept in good repair. Streets were kept exceptionally clean by convicts doing forced labour. The rectilinear streets of Valletta kept the air cool and fresh. Only the residents of the Manderaggio of Valletta had an unhealthy aspect owing to the large number of people that were crowded in squalid and poorly ventilated quarters.

Diet

The meals of the peasants were frugal. Food consisted of coarse bread, garlic and oil, cheeses and olives, salted fish such as sardines and anchovy, pumpkins and other vegetables such as cucumbers, peas and cauliflowers of excellent quality. Only water was drunk during meals. Fruit came in various forms (watermelons got a special mention), however, except for oranges, fruit was of poor quality and was often eaten "unripe". The flavour of the meat, "the cattle being fed on cotton seed, is not good and is particularly lardy". Similarly, he says that the potato crop in Malta was inferior to that consumed in England. Sheep and goats produced excellent milk. Fish caught the previous day was strictly prohibited to be put on sale.

As an aside, and without any hint of derision or sarcasm, Hennen remarked about, "the exhalations of oil, garlic and salt-fish and the smells produced from the smoke of tobacco which emanate in gaseous forms from a full-fed native exceed description".

The rich consumed a small amount of meat, their daily diet consisting of bread, pasta and vegetables, fish, fresh or salted pork, fowl, fruits, and Sicilian wine. On feast days however, an extra amount of meat, poultry and sweets were consumed in enormous quantities and "with great voracity by the numerous guests". After lunch all enjoyed a siesta that extended until 2pm.

Diseases according to locality

Hennen and others believed that certain diseases were more prevalent than others, some being specific to particular localities. Fever occurred especially at Musta, Naxxar, Curmi and Tarxien, all localities being close to marshlands. He attributed the fevers to the bad air, which he called "miasmata" from stagnant waters that exuded putrid smells. The inhabitants of Musta and Naxxar were particularly affected as many of them laboured in fields that were close to the marshy land of Pwales. The inhabitants of Curmi and Marsa were similarly affected. Zejtun was notorious for cases of eye diseases, Zurrico for the diseases of the lungs - "cough" according to Hennen, while Bircircara stood out for problems of stone bladder.

Hennen averred that such ailments occurred especially in the autumn months. Fever, which caused a 10th of deaths in Malta could also be caused by infections that follow flea, mosquito and "culex", (that is sandfly) bites, that "throws the delicate newcomer [a reference mainly to the British troops] into a state of fever". Hennen suggested that insect bites could be avoided by applying a liquid potion of lime juice and oil, especially on the Achilles heel, where these insects mostly attack.

Medical and health institutions

The main civil hospital was in Valletta, located close to the Sacra Infermeria, the latter building having been taken over by the French during their short tenure of Malta and later retained by the British as their own main military hospital. Male patients were accommodated in a nearby convent known as Le Convertite, which could take up to 200 patients, while the female hospital was in a building known as La Cassetta, which accommodated 150 patients.

Added to these there was the Santo Spirito in Rabat that had no more than 30 beds - all the patients there were female. Another hospital was in Rabat, Gozo. Then there was also the Ospizio in Floriana that was used for lunatic cases, decrepit old men and women and foundlings. Hennen noted the high mortality rate among foundlings.

Health concerns and hygiene were very closely regulated by the police establishment, the reason being that this department was the one that enforced isolation and looked after public hygiene in order to avoid the spread of epidemic outbreaks such as the notorious plague. A police physician in Valletta took care of health matters that included registration and cause of deaths, post-mortems and the examination of prostitutes for syphilis. Other police physicians in various districts in Malta reported to the Valletta station. Since 1924, overall responsibility for national health issues fell under the supervision of the Superintendent General of Quarantine. An appendix in the report described at length the health protocols to be observed by local health inspectors on ships arriving in Quarantine Harbour.

Individual family doctors were available in most towns and villages. There were established tariffs for doctors who conducted medical check-ups at the patient's residence or at the doctor's own clinic or residence. A doctor in Valletta would charge 6 tari (two and a half pence) for a consultation; for the same doctor to visit a patient in say, Zabbar or the nearby villages the fee would rise to 3 scudi. The fees varied also according to the time of day when the visit took place, the type of disease being treated and the quality of the medical intervention if any.

Popular remedies

Both Maltese doctors as well as patients were content to stick to traditional medication. "If the doctor tried something innovative the patient would shun that doctor." Unlike the English, Maltese doctors disliked drawing blood by leeches. However, Hennen claimed that medical practice in the civic hospitals was up to standard.

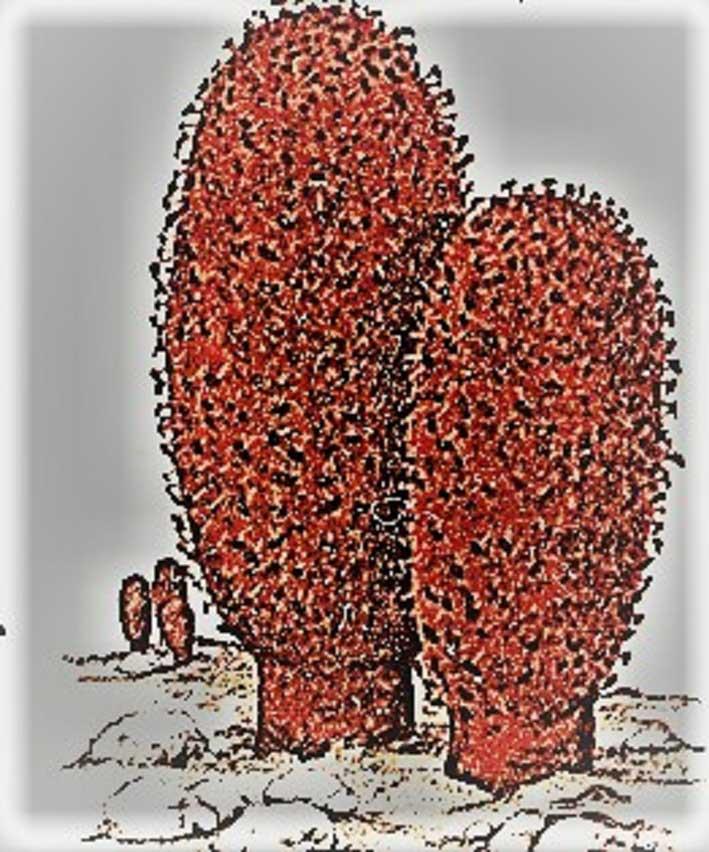

People often resorted to traditional remedies such as almond oil and herbs, the former considered a panacea. The rock earth from St Paul's Grotto was still resorted to, while the so-called Fungus Melitensis, once a popular remedy harvested from the Ġebla tal-Ġeneral, had in Hennen's time, "fallen into disrepute".

Ophthalmia

Hundreds of Maltese were afflicted by diseases of the eyes. Hennen believed that the hot climate, especially in the summer and autumn months was a major cause as was the evening dew, the glaring sun on the rock surface and dust in the air. Hennen, however, was more inclined to blame the scirocco for eye infections. He mentioned the great number of blind men who earned a living by becoming musicians.

Bowel afflictions

Next to fever, affliction of the bowels in the form of diarrhoea and dysentery were the most common ailments, causing a seventh of all registered deaths. Worms in the bowels, albeit not considered serious, were very common. The Maltese attributed these to wheat which was no longer being imported from Sicily, but from Odessa and Egypt. Convulsions and other infantile diseases were very frequent and often deadly.

Pulmonary afflictions

These were classed under six headings: "cough, haemophthisis, phthisis pulmonaris, pleuritis and pulmonic". Hennen added "consumption" to the list, a vague term, according to him, albeit it being very contagious. Pulmonary diseases contributed to one in every 11 deaths. While these afflictions were common, they were quite rare among Maltese soldiers. Hennen attributed this to the fact that these were usually healthy recruits who would otherwise have been dismissed. Diseases contracted by the Maltese regiment were slight and simple, namely fever, ophthalmia and venereal [the latter clearly demonstrates that back then, the local male population was not oblivious to the charms of prostitutes!]

Epidemic diseases

Varicella was very common among children aged between two-and-a-half to six years and appeared every summer but was never lethal. According to Hennen, in 1824, scarlatina anginosa and measles were probably imported by the 95th Regiment, recently arriving from England. Hernia and hydrocele [infection of the testicles] and infection of the livers under various forms, were also very common, the latter, he noted, being on the increase.

Health and the British military

The troops were billeted in barracks mainly round the harbour towns, namely inside Fort St Elmo, Floriana, the Cottonera, Fort Ricasoli, Fort Tigne, Fort Manoel and Fort Chambray. The location of these barracks provided clean air for the garrisoned. However, the bomb-proof barracks lacked sufficient ventilation for the men quartered inside.

The soldiers had their own military hospitals. One was the general hospital, housed inside the Sacra Infermeria. Then there was another hospital in Floriana that served the troops billetted there. The third hospital, which was inside Fort Ricasoli served soldiers in the Cottonera area and for chronic cases. Hennen also mentions a naval hospital located at an unspecified former convent "on the other side of the harbour from Valletta".

Hennen suggested that a new large naval hospital should be built on the Bighi promontory. This project was actually initiated just four years after his death.

Thanks to Michael Cassar for having brought the publication to my attention

and for having gone through my summarised rendition of the text