The period 1914-20 is recognised as one of the most turbulent phases in Malta’s socio-economic and political development as a nation-state. Not only were the Maltese suffering the run-down effects of the First World War but a pandemic known as the Spanish Flu was afflicting the Maltese Islands. High price rises in the essential basic commodities such as bread were the last straw that broke the camel’s back and burst the proverbial bubble in the face of the British. This reached a climax in the Sette Guigno riots.

The origins of the name Spanish Flu is often times misleading in thinking the pandemic originated in Spain, which is considered unlikely. It was only because news of the sickness first made headlines in Madrid in late-May 1918 and coverage only increased after the Spanish King Alfonso XIII came down with a nasty case a week later. Since nations undergoing a media blackout could only read in depth accounts from Spanish news sources, they naturally assumed that the country was the pandemic’s country of origin.

Preliminary report and statistics

In a Preliminary Report dated 16 December 1918, influenza or the common flu was seen as occurring infrequently as a cause of death in Malta’s mortality statistics.

In fact, within the 30 years prior to 1918, it was only in 1892 and 1900 that the deaths attributed to influenza rose to 66 and 78 respectively from a yearly mortality which is rarely ever more than 10.

The incidence of flu had always been limited to the winter and early spring. In 1918, however, after the ordinary seasonal prevalence, cases of influenza continued to be reported which from nine in June, rose to 33 in July and 50 in August. Up to December 1918, with the exception of two cases in March, the disease had not occurred in Gozo. In September the number of cases in Malta went up to 3,197 and 232 were notified in Gozo.

The height of the epidemic was reached in October with 4,651 cases in Malta and 1,203 in Gozo, the number coming down during November to 1,306 and 510 respectively.

The downward course of the epidemic was well maintained, as shown by the number of cases and deaths registered up to December:

Malta

1 December to 10 December

Cases

195 Influenza, 13 Bronco-pneumonia, 1 Pneumonia

Deaths

4 Influenza, 2 Bronco-pneumonia

Gozo (same period)

100 cases, 6 deaths

With regards to statistics of cases it was noted that to the notified incidence of influenza, cases reported as Bronco-pneumonia and pneumonia, were to be added. Though a small proportion of these cases may have been reported already as influenza, and a few others may have not been a manifestation or complication of influenza infection, the error of thus overestimating the extent of the diseases could be very appreciable and was amply offset by the number of slight infections escaping notification, especially in instances where no doctor was called in.

Infection from person to person

Infection from person to person appeared to be rapid and easy and this accounted for the wide dissemination in a short time. The very great majority of cases were of a mild type; some however, developed Bro-pneumonia complications and showed a considerable liability to end fatally, while two to three cases of a septicaemic type had also been observed. Such cases appeared to contain the virus in an exalted condition and infection from them was more likely to be followed by serious consequences. The severe cases had been noted mostly among members of the poorest classes.

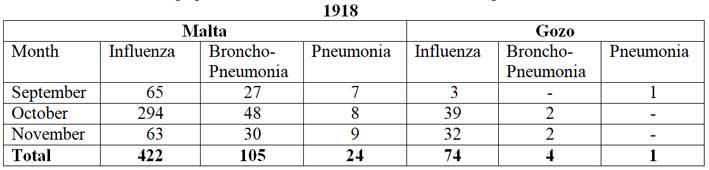

Deaths in the civilian population of Malta and Gozo between September and November 1918

It was assumed that the registered incidence in September to November represented the actual prevalence of the disease; the case mortality for both Islands during the period would have been 5.5%. It could then be safely assumed that the registered incidence was short by at least one half of the total number of persons attacked. Reckoned on this basis, the fatality would have been expressed as 3.7%.

The number of deaths, including those for July and August as a percentage of the population would have given a death rate of 2.9 per 1,000 in the case of Malta and 3.3 per 1,000 in the case of Gozo.

As no foreign statistics were available yet, the extent and fatality of the disease could not be compared with its prevalence abroad. It was noted that from information published so far it appeared that the Islands fared better than other countries.

Precautionary measures

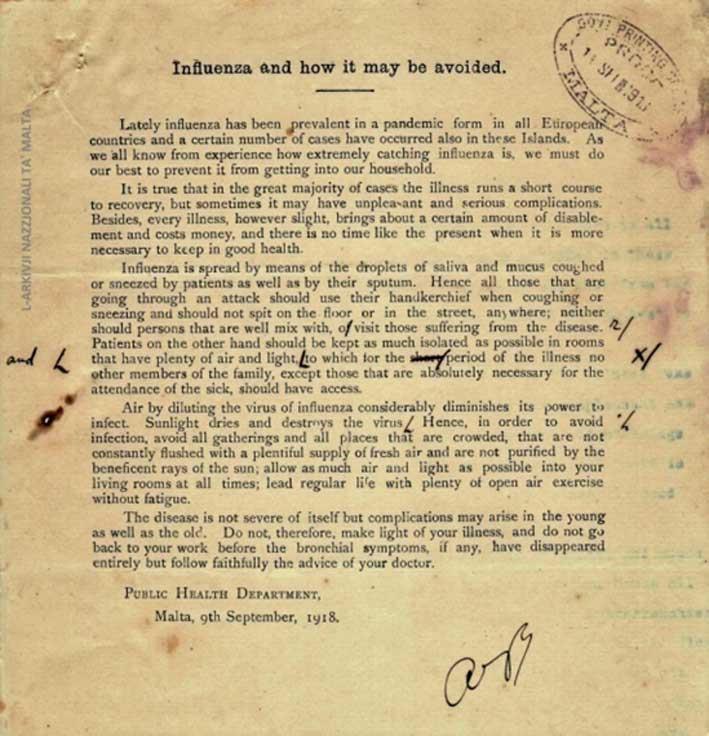

As soon as the disease showed a tendency to spread, towards the second week of September, special precautionary measures were adopted as follows:

· Publication of leaflets and posters calling attention to the extreme infectiousness of the disease, the ways it is transmitted, the value of air and light in dwellings and of personal and domestic cleanliness, the necessity of taking proper care of oneself as soon as the first symptoms appear until complete cure and of keeping the sick apart, as much as possible, from the other members of the household.

· Isolation at home or removal to Manoel Infectious Diseases Hospital of severe cases, and of cases complicated by pneumonia or broncho-pneumonia; disinfection of rooms, beddings and linen of same.

· Removal to Manoel Infectious Diseases Hospital of influenza cases developing in harbour and, as much as possible, of cases without proper care and accommodation.

· Prevention of overcrowding in public places, cinemas, theatres and other places of amusement; cleanliness, aeration and disinfection of same.

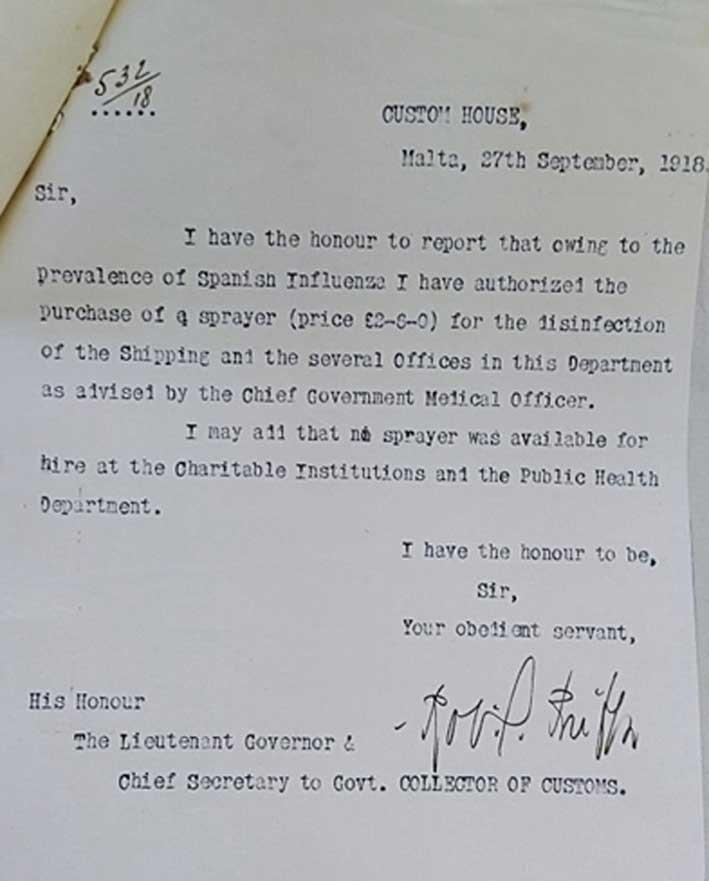

· Disinfection of public places with large concourse of people, railway carriages and ferry boats. The Collector of Customs authorised the purchase of a sprayer (price £2.6 for the disinfection of the Shipping and the several Officers in his Department as advised by the Chief Government Medical Officer. He also noted that no sprayer was available for hire at the Charitable Institutions and the Public Health Department.

· Reduction of visiting in hospitals and other charitable institutions; discontinuance of pawning of clothes, etc.

· Closure of government schools. As cases of influenza occurred in Gozo, the Assistant Chief Government Medical Officer and Superintendent Dr A. V. Bernard MD of the Public Health Office submitted a notice dated 23 September 1918 to the Lieutenant Governor that government schools at Gozo were to be kept closed until further notice. Another notice by Dr Bernard dated 27 September, it was suggested to the Lieutenant-Governor that the Lyceum, the Secondary School for Girls and the Secondary School at Gozo will not re-open for the present. He also recommended that the Elementary Schools will not re-open on 1 October but remain closed until he reported further. Increased visiting of dwellings etc. by sanitary inspectors.

· Temporary surveillance of all arrivals from abroad and disinfection of personal belongings in certain cases.

Dr Bernard wrote to the Military Authorities on 20 September 1918 on the situation of hospitals, ambulances, doctors and sanitary inspectors. He also summarised the principal precautionary measures adopted as follows:

· Isolation of cases of the severe type and of other affected persons who were not suitably housed

· Disinfection of premises and belongings after death of patient or his removal to isolation hospital

· Surveillance, and, in certain cases, disinfection of contacts

· Issue of leaflets containing information about the disease

· Recommendation to disinfect daily cinemas and theatres, railway carriages, launches, premises of the Courts of Law, etc.

Hospitals and ambulances

With regard hospital accommodation, Manoel Hospital and Apartment No. 9 at the Lazaretto were seen as sufficient.

On the Governor’s suggestion, St John’s Military Hospital was to be made available for civil influenza cases and it was suggested that it would be still more advantageous if instead of the St John’s, a part of Manoel Military Hospital in the vicinity of the isolation hospital, would be made thus available. The latter arrangement was seen as having the great advantage of concentrating cases in one locality and save on installing a separate administration. The close proximity of the disinfecting station at Manoel was also seen of great importance.

Owing to the lack of motorcars, the authorities were finding increasing difficulty in coping with the number of cases, which were scattered all over the island. It was suggested that the Military authorities be approached with a view to ascertaining whether they would allow the use of motor-ambulances. Ambulances were needed not only to carry patients but also bedding and other. Patients and bedding would also be transported to disinfection stations and ambulances were also required for use by medical officers for urgent visits.

Doctors and sanitary inspectors

Certain doctors were transferred to help in controlling the outbreak. For example, Dr Calleja, A/Q.M.O was detached from his quarantine duties to help in the work connected with the outbreak. Another extra Q.M.O was to be employed at 10 shillings per day to take Dr Calleja’s place at the Grand Harbour. Dr Vella, who worked at Manoel Hospital and the Lazaretto, could not be spared under the circumstances that prevailed.

Dr Bernard also presented government with an earnest appeal for the consideration of the position of the insufficient salaries of sanitary inspectors. He pointed to the demoralised state of these workers in spite of the efficiency of their work. Their work was seen as assuming greater importance. Dr Bernard also reported that three sanitary inspectors had reported sick the day before. These were irreplaceable and the position was seen as disquieting. Dr Bernard ended his report by suggesting a measure of urgent expediency whereby sanitary inspectors be granted a bonus equivalent to at least 30% of their respective salaries. He noted that should the work of the sanitary inspectors break down, the consequences would cause much heavier expenditures than the one he was proposing.

Malta Labour Corps from Taranto

During the last period of the war, around September 1916, about 800 Maltese and Gozitans volunteered to serve in the Labour Corps to help the British in their battle against German and Bulgarian troops in Salonika, Greece and Taranto, Italy. After the war, these men returned back to Malta in 1918.

Dr Attilio Critien MD, the Chief Government medical officer addressed a Minute to the Lieutenant Governor on 20 November 1918 whereby he reported about the great difficulties that were being encountered in carrying out disinfection of persons belonging to the Maltese Labour and Employment Corps on arrival in Malta. The wording used to describe these men was: “They generally arrive in great batches; this together with the fact that they mostly belong to a very unruly class, makes their control quite impossible by ordinary means.”

The day before 164 men returned from Taranto by S.S. Heroic. On arrival, they refused to proceed to the Lazaretto. They left the ship on dghajjes and landed at the Custom House, where notwithstanding all persuasion; they persisted in their refusal and finally forced their way out.

In order that the above would not happen again, it was requested that the Naval and Military Authorities would be approached and put in orders that all labourers arriving in Mala under the Naval and Military Authorities were to undergo disinfection before they were allowed to go home and that the respective authority should retain control of the men until disinfection was over.

Disinfection took a very short time and was not in any way a hardship on the men. The enforcement was seen as constituting a measure of protection for the Naval and Military and Civilian population.

Purchase of Sprayer

Cinema regulations

On 27 September 1918, a draft of proposed regulations for places of entertainment under Article 38 of the Fourth Sanitary Ordinance, 1908 was presented by Dr Bernard MD to the authorities for consideration. The list of these rules is summarised as follows:

· Every keeper of a cinematograph, theatre or any other place of entertainment was to keep all parts of the premises where such entertainments took place perfectly clean and thoroughly ventilated to the satisfaction of the Superintendent of Public Health.

· Every keeper was not to allow a number of persons larger than that for which sitting accommodation was provided to remain on such premises and shall otherwise conform to the instructions which the Superintendent would give to prevent overcrowding in such places.

· Every place was to be disinfected at least once daily in the manner prescribed by the Superintendent of Public Health.

· Every director of a school, including schools for religious instruction, was to keep his school clean and ventilated to the satisfaction of the Superintendent of Public Health. He was also to conform to the instructions the Superintendent would give to prevent overcrowding in his school and for disinfection of the school premises.

· In case the Superintendent of Public Health considered that any cinematograph, theatre or other place of entertainment, or any school, including school for religious instruction was not kept sufficiently clean and ventilated or was so overcrowded that it would prejudice health, it was lawful for him to order the immediate closure and the keeper or director concerned would be bound to keep his place closed until it was satisfied that no danger to health was present following re-opening.

The Spanish Flu claimed the lives of nearly 500 Maltese and Gozitans as it tapered away from the Maltese Islands by 1919.

The Aftermath

After the ravages of the First World War, the ensuing Spanish Flu pandemic and the Sette Giugno riots of 1919, (which left at least four Maltese dead), the British authorities governing the Maltese islands realised more than ever before, the seriousness of the situation.

The labour and economic situation was considered by the British Authorities such as to make the Maltese, naturally credulous and easily led by agitators to ascribe all their privations to the shortcomings and general policy of the British Government.

It was acknowledged by the British authorities that the high price of essential commodities of life and increasing rate of unemployment was the cause of the general state of discontent which prevailed.

The poorer classes of Maltese society depended heavily on private philanthropic initiatives and also those by the Church charitable institutions. Bread and soup tickets were distributed. For the two years 1917-1918 an average of nearly 25,000 tickets per month were issued representing £5,000. The charitable institutions also accepted donations by private persons.

Receipt from the Comptroller of the Charitable Institutions dated 2 September 1925 whereby Carmelo Caruana donated 15 Shillings for the maintenance of Francesco Farrugia who was in the Central Hospital covering the period 17 August to 16 September 1925 (30 days)

Receipt from the Comptroller of the Charitable Institutions dated 2 September 1925 whereby Carmelo Caruana donated 15 Shillings for the maintenance of Francesco Farrugia who was in the Central Hospital covering the period 17 August to 16 September 1925 (30 days)

In a Memorandum dated 9 July 1919 (exactly one month after British troops killed four Maltese men), Viscount Milner wrote that the immediate alleviation of the situation was that the price of bread, which was the staple food of the population was not to exceed four and a half pence per rotolo, which was considered as a reasonable price (but not a low one as compared with the pre-war one).

7 June 1919 (Photo: From a Private Collection)

Viscount Milner also recommended that extra public works on roads, etc. would be carried out in various parts of the Island. These measures, he reiterated would necessarily involve expenditure from Imperial funds. This employment in public works was seen as a temporary expedient and for any permanent relief more comprehensive measures were required.

Due to its geographical position the British did not want to give up Malta as it was considered as the “Fortress of the Empire”. They did not want to cede Malta to any other power or give any measures of autonomy to the Maltese that might be prejudicial to their Imperial interests. Hence, it was in their interest and responsibility to promote the interests of the inhabitants of the Island. Hence, this entailed preparation for expenditure which this responsibility entailed.

Some of the suggested measures to stimulate employment and the economy in the light of the above responsibility were as follows:

· Maltese labour was to be employed to the fullest extent by both the Navy and the Army even though such employment was not the most economical arrangement possible and even though the result would not always meet at first the same high standard of workmanship.

· Services, which were necessary but not urgent, and which would without any great loss to efficiency be postponed would nevertheless be proceeded with in order to maintain a continuous and constant employment of labour.

· Recognition was to be given to the Civil Government as a Department of State as a purchaser of foodstuffs and other necessaries, the distribution of which it would directly control.

· Local sales would be allowed of commodities surplus to Navy and Army requirements even though higher prices might be obtained elsewhere.

· Financial support would be permitted to industrial enterprises which in the opinion of the government would directly benefit the community.