Your government was short-lived, lasting only 22 months. You called for an early election after Dom Mintoff voted against your government on a motion regarding the conversion of Cottonera Creek into a modern yacht marina. Earlier in the legislature, Mintoff had abstained on Budget votes, and the government had been saved by the Speaker's vote. Why, do you think, Mintoff chose to bring your government down? Was it a clash of personalities?

I can only interpret, as I see it, what Mintoff did. Indeed, there are many factors that went into the mix and they cannot just be summed up in a question and answer session like the present one. If time allows, I plan to write a memoir on those days... as a continuation of my Confessions of a European Maltese where the truth as I see it will hopefully, be laid out in full.

However, on the point about a clash of personalities: Many moons ago, my first meetings with Mintoff had always been learning experiences for me, which I valued... starting with 1966 when he told a group of University undergraduates, of which I was a member, to beware of the "priests" for they would not like our project to set up a free speech debating society. Actually soon after, seminarists turned up at the group's general meeting to vote us out in a well-prepared block vote.

Over the years, I totally endorsed his strategic choices when they mattered, still agree with them (like neutrality for instance or the centrality of a Mediterranean vision for Malta), though obviously they needed to be updated with the passage of time. That in part was also my project. But over the years too, I increasingly could not accept the idea that whatever he said or wanted made sense just because he knew best. Nor was I impressed by his style in the later years, which sought to convert straightforward situations into complex games to arrive at unrelated outcomes that were either never reached, or far-fetched, or trivial. The 1998 crisis developed as well from other factors not just because of a "clash of personalities".

Incidentally, you fail to mention two other occasions when Mintoff's behaviour put spokes in the wheel of the government's parliamentary business. On one occasion, when a finance bill was being voted, without any warning, he advised that he would not be attending as he had to fly to Libya. Doing something like this in his time as Leader would have rightly unleashed an earthquake. The bill passed with the Speaker's vote.

Then there was a debate, requested by the Nationalist Opposition, on negotiations with the EU. Between 1992 and 1996, the Nationalist administration, over Labour's protests, had adopted the practice of restricting the time for such debates about EU policy, which we had also requested as an Opposition. They then needed these restrictions to avoid too much embarrassment over their failure to achieve quick entry to the EU, as they had promised in the 1992 election. Now we carried over their practice, not least because it was not a good idea to have extended parliamentary debate on EU relations at a time when we were at a delicate stage of negotiations with the EU on the partnership project. Yet Mintoff wanted speaking time and one could forecast what endless detours and conjectures he would be raising. On the latter count and that of not deviating from the tit-for-tat arrangements that the PN side had itself established, his demands could not be met. So rather than create a "scene" in Parliament, which would hugely benefit the Opposition, the debate was left in suspense.

This was more than vexatious for at the time, internal discussions had started within Labour to table a motion that would seek to establish a political consensus on how to proceed on EU relations. The motion was meant to take account of the then present realities, with a government that opted for a partnership with the EU but equally incorporate the aspirations of the then PN Opposition in favour of EU membership. That motion never saw the light.

Alfred Sant addressing supporters in that famous activity in Vittoriosa which preceded his calling an early election in 1998 (Photo: Times of Malta)

You had linked the vote on Cottonera to a vote of confidence, calling Mintoff bluff. You had said you were prepared to call an election because you did not want to be threatened or blackmailed. Mintoff remained adamant and voted against you. Was there any attempt, before the vote was taken, to reach out to Mintoff to persuade him not to vote against the government?

I never thought and never said that Mintoff was bluffing. What he and those behind him wanted was control. The build-up was for a parliamentary coup d'etat if that control was not achieved. Yes, there were backstage attempts to "mediate". Initially George Abela tried to bridge the arising problems but soon gave up. Dr Karmenu Mifsud Bonnici persisted to the very end. At a very late stage, he asked me whether I was prepared to meet Mintoff face to face, I said yes, and at his request confirmed it in writing by fax. He never came back with a reply or follow up.

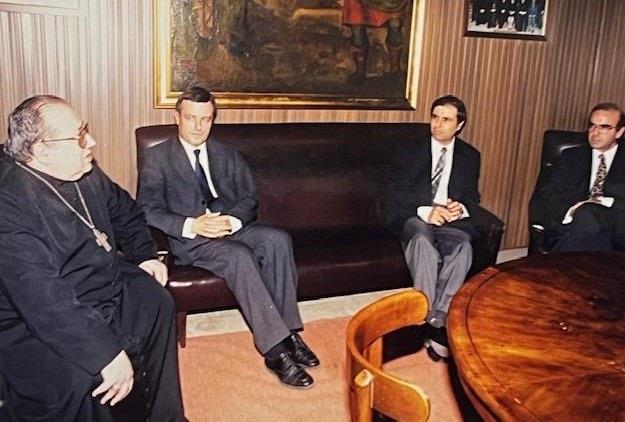

Alfred Sant and his two deputy leaders, George Vella and George Abela, meeting with then Gozo Bishop Mgr Nikol Cauchi

When you called an early election, one of your deputy leaders, George Abela, had been against the idea, so much so that he resigned when you went ahead with your plan. His argument was that it was not in the national interest to hold an early election. He probably also anticipated what was going to happen. Was Abela's position a surprise for you? When you made the decision to call an early election, were you convinced that Labour would win again?

In every step taken during the Mintoff episode, first the approval of Labour's national executive (and the Cabinet) as well as of Labour's general conference was sought. Naturally George Abela was present on all these occasions (Cabinet excepted for he had retired from this attendance having resigned a year before, as general advisor to the government), with full right to intervene. When it became clear that there would be no issue from the Mintoff impasse, I proposed to get a mandate to call an election from the party's national conference. During the discussion on this by the party's national executive, from which I absented myself, the request was unanimously approved by secret vote. There was an agreement that the national executive would second the motion requesting the mandate, that I would be tabling. I think all understood then that Dr Abela was in agreement with this approach. Indeed he went on to a meeting, that same evening, of Labour's women's section to brief them about what had been decided.

The first inkling I got of his dissent was when the general conference had started and I had just finished my input to present the motion. He then whispered that he rather disagreed with what I had said, but to be honest I thought he was meaning some turn of phrase I had used which was over the top, which did sometimes happen to me. He expressed his total dissent when he came to make his speech, which to be honest dumbfounded me and I think many others. So yes, I was completely surprised at this turn of events.

Calling an election was not some gung-ho reaction. Of course, I did not believe that would surely solve the problem by ushering in a second Labour win. The problem was ugly and institutional and dragging on with it would be doing huge harm to the country as a whole. Nor was it just, as some claimed, turning to the country to resolve a party problem. The government was in the middle of an extensive reform programme and the parliamentary impasse was making everything stall. Further loss of credibility would result from treading water or trying to get Mintoff on board by accepting whatever he wanted to achieve.

Some time before this confrontation boiled over, I had met top analysts of a leading financial rating agency. They opined that the Labour government's modernisation policies were totally admirable and they considered our EU policies feasible but there was one big problem: the government was politically unstable. They were correct and this issue had to be faced head-on, but in a democratic manner. Staying on with no change would really be clinging to power for power's sake, while what needed to be done in the national would completely stall. That was not an option that made sense, in my view, from the perspective most importantly of the national interest, but also that of the party.

Labour risked losing votes among those who were sore as their grievances had been overlooked (as they saw it), those who were sore because the ongoing reforms had affected badly their lifestyle and they still had to benefit from any payback, and those who were pro-Mintoff right or wrong. The belief was that to counter these losses, there could be enough people who really agreed the country needed radical reforms, who considered the government needed to be given a proper chance to function and who wanted a real generational shift in decision-making. That belief turned out to be incorrect.

Alfred Sant during a pre-1996 election activity

It must have not been easy for you to take on Mintoff, who was revered by the Labour grassroots. Were you concerned that your clash with him could have ended up splitting the party?

You'd be surprised: the great majority of the real Labour veterans - those who had blindly followed Mintoff's instructions in the 1950s and 1960s - strongly disagreed with him on this issue. His mantra then and later had always been that once the party had democratically decided how to proceed, that decision had to be loyally followed. And now he was breaking his own commandment. Indeed, before every decision in this sorry saga was implemented, care had been taken to open developments to discussion and decision in Labour's institutions. A split in the party was not on the cards though there was some splintering which of course was also damaging since electoral majorities at the time were by post-2013 benchmarks quite small.

You were the only prime minister, since Malta became a Republic, not to nominate a President. This was a time when a nomination needed only the support of the government. I know you had other problems on your mind at the time, but Ugo Mifsud Bonnici's tenure as President was six months away from its end when you called the election. At the time, did you have someone in mind for the presidency? If yes, who?

Professor Edwin Grech.

Part 1: The 1981 election and the transition from Mintoff to KMB

Part 2: The 1980s’ bulk-buying system and public sector employment

Part 3: The Church schools battle and the 1987 constitutional amendments

Part 4: The post-1987 election years and the rise to the Labour leadership

Part 5: A new image, the anti-Vat position and the Cittadin Mobil

Part 6: The freezing os Malta's EU application and the VAT-CET changeover

Next week: The return to the Opposition and the EU referendum