Today, 21 September, marks 54 years since Malta became an independent country. The path to Maltese statehood, however, is one which warrants further study; it was a path that was long in the making, and the end result in 1964 was actually not what much of Malta’s political class initially intended.

Prior to the opening of the negotiations that eventually led to independence, Malta was, in essence, a self-governing colony. The Amery-Milner constitution had in fact provided self-government to the islands in 1921, with a 32-man (women were not allowed to vote or be candidates at that point) legislative assembly being elected. The concept of self-government was retained even after the Second World War, despite some intermittent gaps when it was suspended due to national issues or incidents. Indeed a new constitution with a 40-person legislative assembly was granted in 1947, and self-government remained the order of the day for post-war Malta.

However, times were changing; the war left an indelible mark on Britain’s economy, and while governments like that of Winston Churchill in the early 1950s believed in retaining the empire – it was becoming increasingly clear that the once great British Empire was losing influence on the global stage.

In Malta meanwhile, political heavyweights such as Dom Mintoff and George Borg Olivier had emerged at the helms of the Labour Party and the Nationalist Party respectively. They both had their own ideas on how Malta’s future should look, and neither of those ideas initially involved independence from Britain. By the 1950s, a revision to Malta’s future was on the agenda of every political party on the ballot sheet.

Borg Olivier wanted Malta to retain close ties with Britain, and take what was known as ‘dominion status’, much like Canada, Australia and New Zealand. This was a sort of half-way road to independence that would have led to self-determination, except for foreign and defence matters, which would have been the shared responsibility of the UK and Malta.

Mintoff meanwhile wanted Malta and the Maltese to be held on par with the British, and to attain that he believed in going for integration. This essentially meant that Malta would become a part of British territory not as a colony or a dominion, but as an actual constituency.

Labour won the 1955 election with 23 seats out of 40, and that led to Mintoff kick-starting the process for integration. The negotiations were tough, and the discussions involved subjects such as religion – Malta was, of course, Roman Catholic whilst the UK was primarily Protestant, political representation – Mintoff wanted the Maltese to have seats in the House of Commons, and Britain’s economic contribution to the island – Mintoff wanted the Maltese to have the same standard of living as the British.

However, an agreement was reached; Malta was to have three seats in the House of Commons, the Maltese Parliament would retain authority over all affairs except defence, foreign policy, and taxation while the Maltese were also to have social and economic parity with the UK, which would be guaranteed by the British Ministry of Defence – the islands' main source of employment.

The proposals went to a public referendum in February 1956. Both the PN and the Church remained vehemently opposed to the idea of integration and encouraged their followers to not vote altogether, in the hope that the reduced turnout would render the referendum result inconclusive. The election had a turnout of 59% - equating to around 90,000 people – and 77% of those who voted, voted in favour of integration. Mintoff took the result as a victory, whilst Borg Olivier argued that the low turnout – less than two-thirds of the electorate – rendered the referendum inconclusive.

Amidst the arguing around the result of the referendum, the British put forward proposals to reduce the Defence Expenditure, which would affect those employed at the dockyard. Mintoff was furious. The proposals went against the promise the British had made in the initial agreement before the referendum, wherein they guaranteed that they would help resolve the unemployment problem that had enveloped post-war Malta.

Mintoff insisted that not a single dockyard worker would lose his job, but the British could give no such guarantee. As a result, a resolution was passed unanimously in the Maltese Parliament on 30 December 1957 – the Break with Britain Resolution.

Malta’s political class basically declared that this tiny island with no natural resources, which depended heavily for survival on the British military presence, would sever its ties with the colonial masters.

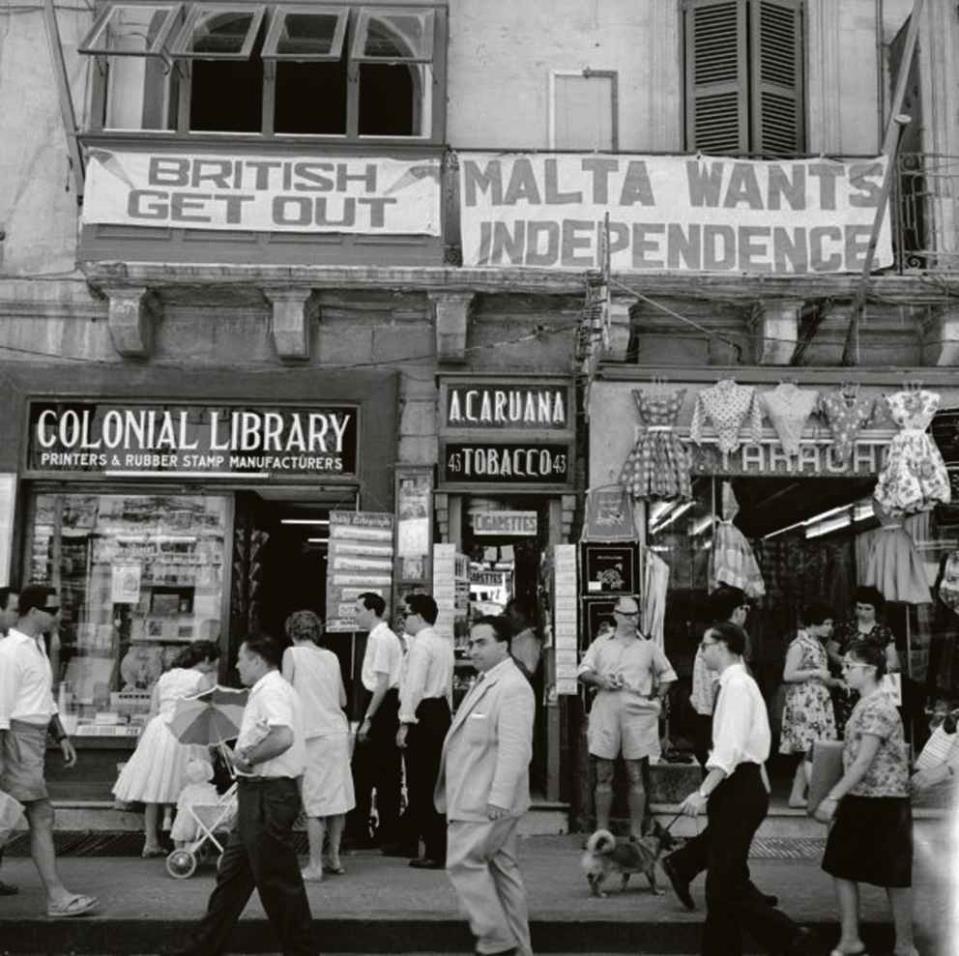

The integration proposal collapsed, and Mintoff submitted his resignation along with all MLP deputies on 21 April 1958, stating that he will govern from the streets. Anti-British riots broke out across the island as a result. Borg Olivier was asked to form a minority government in place of Mintoff’s, however, he too refused. As a result, the MacMichael Constitution of 1947 was suspended and the governance of the island was taken over by Britain.

It was only in 1961, after four years of direct rule from Britain, that Malta was awarded a constitution. Known as the Blood Constitution after Sir Hilary Blood, who chaired a constitutional commission, the supreme law made provisions for elections to be held once again. The Blood constitution, whilst restoring self-government, took away control of the Police Force from the Maltese government – a notion which enraged both the PN and the MLP. In fact, both parties’ manifestos made sure to specify that if elected, the police force would once again be transferred under the control of the Maltese government.

The first election under the Blood Constitution was to take place in 1962. Whilst both major parties made mention of the police force issue, the main bone of contention was undoubtedly on what the future of the Maltese islands should hold.

Both the PN and the MLP believed that complete independence was now the only option for Malta, however, they differed on how it should be brought about.

The PN wanted to attain independence and then join the Commonwealth whilst also maintaining close ties with Britain through the signing of a financial aid and defence treaty. They were also in favour of joining NATO and taking the side of the West in the Cold War that, at the time, was at its peak.

The MLP meanwhile wanted to first attain independence and then decide with whom to negotiate for aid and defence issues. They preferred to work on a system of neutrality as regards to international politics, rather than joining either side of the Cold War.

Mintoff and his party, however, had become embroiled in a social conflict that would come to be a defining factor in the eventual election. Archbishop Michael Gonzi was alarmed at Mintoff’s close stance with Communist leaders and began to see how as a threat to the Catholic faith in Malta. Mintoff himself saw Gonzi as the biggest obstacle to the modernisation of Malta which, he believed, could only come through the secularisation and hence separation of the State from the Church.

Mintoff put forward his so-called sitt punti which included points such as the introduction of civil marriage and the removal of the Privilegum Fori. Both figures proceeded to paint each other in the most negative light possible with Mintoff depicting Gonzi as a British collaborator who was against Independence and Gonzi depicting Mintoff as an enemy of the faith. Things came to a head when on 8 April 1961; the Bishop gave a “personal interdict” on the entire Labour Party executive, making it a mortal sin to vote for the party.

Such a delicate social and political environment resulted in the creation of a number of smaller parties.

The Partit tal-Haddiema Nsara – or Christian Worker’s Party – founded by Toni Pellegrini, was one of these party. Their aim was to provide a viable worker’s alternative to the MLP that didn’t go against the Church and in fact, it was endorsed by Archbishop Gonzi. Besides this, Pellegrini’s party was also against the pursuit of independence at this point in time as they believed that Malta was not economically ready for this venture.

The Independence issue also divided supporters of the Nationalist Party as well, and those who did not favour it founded a new party; the Partit Demokratiku Nazzjonalista (PDN). This party was led by the journalist Herbert Ganado and, much like the CWP, they believed that Independence was not a good idea due to Malta’s economic weakness at the time.

Another party contesting this election was the Progressive Constitutional Party (PCP), led by Mabel Strickland. The agenda of this party was the complete opposite of the other four, in that it thought that the Blood Constitution was a step forward for Malta and that Malta should be seeking a closer relationship with Britain rather than independence from it.

The Democratic Christian Party, led by Chevalier George Ransley was another participant in the election but is of little note. In terms of Malta’s future, it vaguely insisted that Malta should be given a constitution it deserved. This implied that they were against Independence but also against the terms that the Blood Constitution had set for Malta.

The result of the election showed just how divided the Maltese were in how they were thinking. Out of the six parties, five of them won seats in the legislative assembly. In an election with a 90% turnout, Borg Olivier’s PN won 42% of the vote and 25 of the 50 seats on offer. Mintoff’s Malta Labour Party was next, winning 33.8% of the vote and taking 16 seats. Both the CWP and the PDN won 4 seats – or around 9% of the vote, whilst Mabel Strickland was the only member of the PCP to win a seat as the party won around 5% of the vote. Ransley’s Democratic Christian Party won 699 votes, but nothing more than that.

The PN avoided having to enter into a coalition to gain a majority, as Coronato Attard crossed the floor from the PDN to the PN to give them a marginal seat majority in the Assembly. With the election, it was down to Borg Olivier to attain independence for Malta.

The first order of business, however, was to deal with the constitution, and he successfully negotiated to remove some constitutional measures that he disagreed with, such as the police force being under the British government.

Malta’s independence was eventually ironed out and would see Malta receive a total of £50 million to help the country diversify its economy from one reliant on Britain to a country dependant on its own economy. In addition, Britain was able to hold on to some military facilities, due to the Cold War situation, for a number of years.

The proposed independence constitution went to a referendum in May 1964, where it passed with a 54.5% majority of the 80% turnout. Malta became an independent nation on 21 September 1964, when an emotional ceremony was held to commemorate the occasion.

By 1966, when the next elections were held, the Maltese electorate drifted back to their traditional political choices; none of the CWP, PDN or PCP was ever elected into Parliament again, and Malta wouldn’t see a third party elected into Parliament till 2017 when the Partit Demokratiku elected two MPs.